Early career: Forging a path

Starting out in law can be tough, with gratification clouded by long hours and paperwork. Two junior solicitors share how they are finding passion and purpose, amid calls from experts to create better structures to support the profession’s future leaders.

“I never thought I would be a lawyer,” Lucinda Walder declares at the beginning of her interview with the Journal, speaking from Legal Aid NSW’s Orange bureau, where she works as a solicitor for the organisation’s Civil Law Service for Aboriginal Communities.

“My dad finished school in year 10 and managed a hardware store. He was cluey but did not go any further. My mum was studying to be a teacher the same time I was studying law, but she did it remotely. We didn’t have a lot of family who either finished high school or went on to do further education,” Walder explains. “The school I went to told me I would not amount to anything more than admin. I became stuck in that mindset for a while.”

The proud Indigenous woman, from Nowra on the NSW South Coast, had a non-linear path into the legal profession, one that twisted and turned for 10 years until she was finally admitted as a solicitor in February 2022. Although she describes this journey as “one of the greatest” of her life, the 29-year-old mother-of-three admits it has not always been smooth sailing, and at times questioned whether a legal career would materialise.

“Other people came from the same background as me … working out what university life was like, and what our careers could look like. It felt like a family.”

As a high school student, Walder became curious about the law after witnessing several family members engaging with the justice system in a negative way, including her grandfather, who spent time in prison for unpaid fines. A longing to understand the wheels of justice propelled Walder into work experience with the local Aboriginal Legal Service. Then came what she describes as her “pivot point”, when she was accepted into the Indigenous Pre-Law Program at UNSW on the path to studying law and subsequently packed up her life in Nowra and moved to Sydney.

“I knew I wanted to do law, but I didn’t know if I wanted to be a lawyer or work in policy at that time. I just knew that was the area I wanted to be in because I was always passionate about fighting for justice and advocating for Aboriginal people,” Walder says.

Walder praises her experience at UNSW and the support of the Aboriginal Student Centre, Nura Gili, for supporting her through her degree.

“Other people came from the same background as me (my mum grew up on the mission and my dad grew up in town, with not much). There were other Aboriginal people from around the country, coming together for a common cause, working out what university life was like, and what our careers could look like. It felt like a family.”

However, Walder says most of her colleagues in her Pre-Law cohort dropped out of their degrees, which she attributes to the “culture shock” of moving from the bush to the city.

The statistics on law dropouts are unsurprising to Shaaron Dalton, the managing partner at Eaton Strategy + Search, which provides strategic advisory and talent search services to law firms and corporates. Dalton has worked in legal recruitment for the better part of 30 years and is best placed to comment on the “trigger points” for lawyers, at all stages of their careers.

Dalton is calling on firms to create better structures to support junior lawyers, to prevent the haemorrhaging of talent that is currently plaguing the profession. While there are processes in place to transition lawyers into the workforce, like the mandatory Practical Legal Training and graduate programs, Dalton has observed how the catastrophic shortage of staff has put pressure on workloads and the ability to provide quality training.

“Back in the 1990s, you would have lots of lawyers at all levels, and a great deal of partner contact. Firms would train lawyers by having them in the room with the partner. But as pressures increased on partners to be more than just a lawyer, … to be a business developer and a manager, they moved away from that style and took more of a mass education approach. This put more onus on senior associates to be the managers of the junior lawyers.”

Dalton says the most common reasons she hears for lawyers leaving the profession in the first two years is that the work is not what they expected, or they want to do something that gives them a greater sense of purpose.

“There are many young lawyers who want to be involved in human rights law, or policy, because they want to feel like they are making a difference … There are more people now that are going to follow those goals, and fewer who are going to hunker down and wait until it gets better. If someone comes to us in the early stage of their career, we tell them to hang in there, find themselves a mentor to help them through this difficult point.”

‘Not the sole identity’

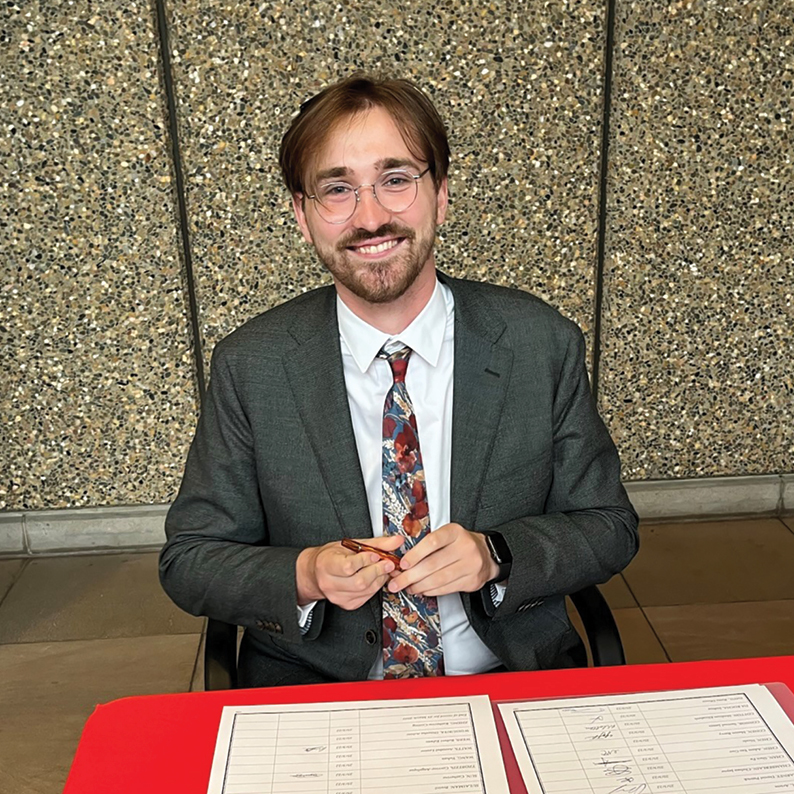

If someone told George Stribling during his first year at law school that he would be a corporate lawyer at a top tier firm, he wouldn’t have believed it. Now the 25-year-old is working in the Pro Bono team at Clayton Utz in Sydney as part of the graduate program.

“I didn’t like the first three years of law school. I wasn’t engaged with it, partially because I was doing it because I could and it felt like the right thing to do, rather than what I wanted,” Stribling admits.

Stribling was 17 and fresh out of high school when he moved to NSW from WA to study law at Sydney University. He tells the Journal it was no surprise that, after his third year, he chose to take a year out from studies to “revaluate his career plan and live his life”. This involved doing transcription work in courts, and travelling around the world, studying audio engineering and volunteering in community legal centres. Until something clicked.

“I think it is a Type A lawyer personality thing where we feel we have to keep on going and succeeding. The idea of taking a year to bum around and not do that is invaluable. But the ability to do that comes from a position of great privilege and I am massively aware of that.

“In terms of a sustainable career in the law, you have to be interested in what you are doing. I think as a junior, you are not necessarily getting the most interesting work. You are the foot soldier; you are the one doing the grunt work. Being on committees is a chance to think bigger.”

“I honestly do not think I would have finished my degree if I hadn’t taken the year out. I certainly would not be doing what I am now, and even if I had gotten here, I probably would not have lasted that long. You need time to not be a lawyer, not be a high achieving university student or high school student. There has to be space for the rest of you.”

Dalton agrees, and sees this as a shifting focus for many lawyers at all levels: “The move towards identifying yourself on factors other than what you do in your career is a good idea for young lawyers because it will calm that anxiety. People who are happy in the law are those for whom being a lawyer is not their sole identity.”

Stribling’s passion area is disability law, and he previously worked at the Australian Human Rights Commission and the Australian Centre of Disability Law while studying. In his current role, there are not always opportunities to exercise these interests, but he keeps the fire lit by participating in extra-curricular activities, and is the current vice-chair of the NSW Young Lawyers Human Rights Sub-Committee.

Not always a smooth landingA Law Graduate Study published in February 2022 by consultancy firm Urbis provides insight into the experiences and career situation of early career lawyers, four years after graduation. Only 70 per cent of the 931 final-year law students surveyed graduated in 2017 with an undergraduate degree. Of alumni, one-third were no longer working in the profession four years on. But encouragingly, of the majority still working in law, 87 per cent said they intended to stay practising. The highest agreement point among respondents was that graduates need more support transitioning into the workforce. Eighty per cent felt overworked, and more than a quarter believed their legal skills lacked relevance to their current work. |

“In terms of a sustainable career in the law, you have to be interested in what you are doing. I think as a junior, you are not necessarily getting the most interesting work. You are the foot soldier; you are the one doing the grunt work. Being on committees is a chance to think bigger.”

Walder’s decade-long path in the law has been filled by work in a plethora of areas, including but not limited to juvenile justice and out-of- home care, fisheries matters for Legal Aid’s Civil Law team, and corporate work for Qantas. Now, as part of her role in Orange, she conducts outreach and runs face-to-face clinics in Aboriginal communities, including at Condobolin, Lake Congelligo and Murrin Bridge.

Although she admits at times it has been overwhelming moving her young family interstate, Walder tells the Journal she is living out the career she has always dreamed of.

“Always aim high. You might not go the direction you think you are going to go, but you must enjoy the journey. A lot of my peers got there faster than I did, but one thing I am thankful for is all those experiences I had along the way. They have made me a stronger, confident solicitor.”

Coming soon:

Part Two – A Parental Pause: Changes to the Government’s parental leave scheme have created a positive ripple effect in private firms across Australia, with an increasing number implementing greater support for families. How is the profession retaining practitioners at this critical stage of their lives and careers?

Part Three – Senior Lawyers: What keeps people in this demanding profession at the senior level? How have they managed to sustain that early dream of making a difference, attaining a prestigious position, and managing the work–life balance?

Part Four – Retirement: What happens at the latter end of a long legal career? Meet three people whose years of practice have brought new learnings on life in the law – and beyond.