The rapid progress of AI is leading to thorny questions about their use and purpose. Chatbots might be here for good, but are they ‘for’ good? A legal researcher chats all things chatbots in the mental health space – and what working principles to apply in legal analysis of the tools.

Where were you when you first heard of ChatGPT?

With the benefit of a few months’ hindsight, it feels like a watershed moment in the history of artificial intelligence: the point where AI really hit the mainstream and infected most people’s consciousness.

But people have been interacting with chatbots in digital settings since well before ChatGPT was a byte in its creator’s imagination. The first chatbot ELIZA was invented in the 1960s. By the early 2000s, chatbots like Smarterchild were not just responsive to questions, they were remembering and piecing together previous conversations, creating something like a personality. Today Siri and Alexa provide you with weather updates before you leave the house.

And now, judges are using chatbots to write their court decisions.

Make no mistake, chatbots are now embedded in our everyday lives, and it looks like they’re here to stay.

But that’s not to say their rollout is blissful and fault-free. Their variety might make the legal analysis daunting but, according to Monash University Faculty of Law PhD candidate Neerav Srivastava, it might be possible to identify working principles.

Chat-what?

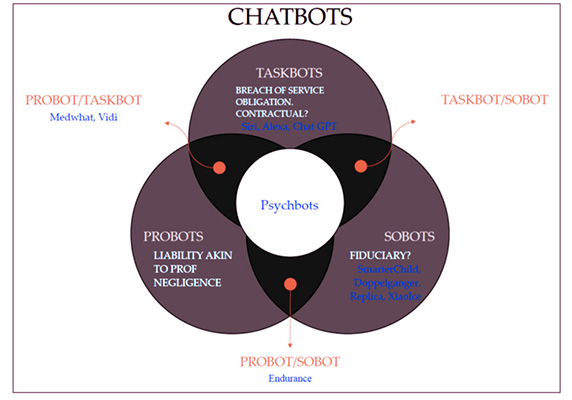

Understanding the type of chatbot is crucial to any legal analysis. Srivastava argues consumer chatbots can be loosely divided into three different categories, which he demonstrates with a Venn diagram.

First, there are taskbots. These include Siri-style assistants, which are basic in their application and execution. Srivastava explains: “You just ask it to do something, and it responds. Either it does it well or it doesn’t do it well. The legal analysis is basically limited to whether or not it has done a good job – something like a breach of contract analysis.”

Second, there are social chatbots. These are chatbots that act as friends, trying to build a relationship with users. XiaoIce and Replika seek to provide friendship, and sometimes love. XiaoIce already has over 660 million users. There is a concerning possibility that this could centre power in the chatbot, which could then misuse the power, Srivastava says. The relationship aspect may lend itself to a fiduciary-type analysis depending on the nature of the relationship.

Third, there are professional chatbots. Srivastava emphasised that these aren’t professionals, and don’t claim to be able to provide the same standard of assistance as professional psychologists, doctors or other service providers, but they do claim to act as a sort of ersatz substitute. Here, professional negligence principles may help.

Srivastava is particularly interested in the use of chatbots in mental health, which he calls ‘psychbots’. Psychbots are one of the first apps to be ‘disrupting’ a profession. About 40 per cent of all current healthcare chatbots are psychbots, according to the researcher; they include Tess, Wysa, and Woebot. Tess alone has eight million subscribers.

Trust issues

These are the sorts of bots that might provide you with suggestions of treatments in lieu of a professional. But they differ markedly from a trained health professional. Health professionals have standing in the community and if something goes wrong patients have recourse via, for example, suing for malpractice.

Conversely, consulting a bot is very different to seeing a person in a clinic or even googling one’s symptoms (we know you do it too!). What these bots do have though, is the ability to generate a relationship with those using them. According to Srivastava, “psychbots appear to compensate for the trust deficiency by building a relationship with users”. Psychbots will, through prompts and actions, become a friend and professional advisor, asking questions to “get to know” a user before spitting out a proposed solution.

But if they’re going to act as a professional advisor, they should adhere to something like professional standards, Srivastava contends. If they abuse a “trust”, that too may have legal consequences.

An extra layer of complexity is added to the issue when you consider that anyone, of any age, can interact with a chatbot. In some medical emergencies, a chatbot can cause more harm than good.

Using the example of child abuse, Srivastava draws a comparison between how a psychbot would react, and how a professional psychologist would react.

“If a child disclosed that they were being abused to a psychologist, the psychologist would be under an obligation to deal with the matter. [Now] you’ve got chatbots that are wading into this space. They’re building a relationship with the user so that the user starts to trust it,” he explains.

But a chatbot isn’t obliged to report any disclosures to it. And this can lead to horrific consequences, like continuation of the abuse or alienation of victims, who, with no positive action taken to stop the abuse, may feel lost, confused and hurt.

“Real harm can result,” Srivastava says. He points to a BBC exposé in which psychbots failed to spot disclosures of child abuse.

“You’ve got professional standards being potentially diluted. It’s probably happening right now, even if people aren’t talking about it.”

‘A chatbot isn’t obliged to report any disclosures to it. And this can lead to horrific consequences, like continuation of the abuse or alienation of victims, who, with no positive action taken to stop the abuse, may feel lost, confused and hurt.’

Much of Srivastava’s work focuses on how common law can act as a backstop while legislators grapple with regulation and monitoring of chatbots.

General principles, or targeted legislation?

“What I’m trying to do is identify general principles that [can apply] when you look at [chatbot liabilities] in the absence of regulation.”

The common law has a role to play, he insists. He uses a soccer analogy as an example: tailored legislation is like the defenders on the team, and common law acts like the goalie, the last line of defence.

“Just because there’s no tailored legislation doesn’t mean that you don’t have protections. Common law … responds by [creating] general principles. What are the basic general principles that we can apply that are chatbot-neutral, that can apply to any chatbot? That’s the way the common law can really help. Then you’ve got these basic protections in place, and then for those chatbots that require specific legislation, that can be developed. The emergence of negligence in the early 20th century is an example of the law responding in a neutral way to technology by focusing on procedure.”

Srivastava says appropriate checks have to be in place. Professionals, and not just techies, need to be an integral part of the design and construction of professional chatbots. For example, mental health professionals should be involved in the design of psychbots.

The second aspect, according to Srivastava, is oversight and monitoring of the chatbots when they’re out in the field. This would ensure that if – or when – serious issues do come up, a professional is there alongside to take a moral action. The extent of supervision depends on the potential risks.

This leads to the third aspect that Srivastava argues for: an escalation protocol for when something goes wrong.

He believes that the principles of Australian Consumer Law (ACL) can be applied:

“Under the ACL, services have to be provided with due care and skill. That’s kind of like the equivalent of negligence, and what’s really important about that is it’s non-excludable. What I’m saying is, if you talk about due care and skill, and take it to include proper design, supervision, and escalation for chatbots, then liability may arise.”

Professionals, and not just techies, need to be an integral part of the design and construction of professional chatbots. For example, mental health professionals should be involved in the design of psychbots.

There is definitely room for chatbots within the health space, Srivastava says – but they need to be appropriately monitored and regulated.

Value and use of psychbots

Using the mental health space as an example, he points to the global mental health crisis and a chronic service gap. He adds that delays in accessing the mental health system are a factor that may drive people to interact with chatbots online, seeking answers as to why they don’t feel well.

Psychbots are also multilingual, so they can be deployed across regions. This could be useful in the case of large-scale destabilising events like wars, providing basic, low-level assistance to those who needed it.

“It’s not that they don’t have a role; it’s that their role at this stage is at the lower level and there needs to be a mechanism when things get more serious, to escalate,” he explains.

“Otherwise, they’re not fit for purpose.”

He’s pushing for quality control of these apps, alongside stronger legal policy frameworks around their use. He acknowledges that for some tech developers and service providers this extra layer of responsibility may be put in the too-hard basket – but he stresses that they should instead see it as an investment that will make their product better, more productive and trusted, and more widely used. Quality can be a competitive advantage.

So what do we do? Is it time to pause further developments in AI and chatbots until we can work out where we’re going and what we’re doing?

Srivastava says that’s probably unrealistic. But it may not be necessary. With general principles in play, especially in key areas like health – which he believes may be the fastest-growing chatbot arena – for now, there is some recourse for any harms that may be done.

Nevertheless, targeted legislation is needed, but Srivastava acknowledges that this will take time.

To lay the groundwork, the legal sector needs to start with the foundations and develop clarity around those foundations. Who would be liable for harm caused by a chatbot – the chatbot developer? The ACL helps in that the person who provides the service is liable. Others may be liable too. Even so, the money might be housed overseas. Addressing the problem may take international coordination.

But recognising that there are general principles, rather than a legal vacuum, may in itself give tech behemoths pause to confront the products they are developing and how they could be improved for the benefit of the wider community, he adds. Ensuring new legislation targets chatbots through their business model could therefore encourage a change.

Defamation woes

When it comes to bots like ChatGPT, the issues of defamation and plagiarism have occupied many column inches and podcast hours in recent months. Srivastava says there is no reason by “in principle or at least in theory”, the owners of chatbots like ChatGPT couldn’t be liable for defamation if the bot says something that is defamatory.

One argument in support of chatbots is that they are no different to Google or social media. Srivastava disagrees. ChatGPT is housed within an app or a standalone, while Google is “plugged into the matrix”, he explains. For Google and social media, a defamatory statement can disperse quickly on the internet. ChatGPT is different.

In addition, a google search “doesn’t purport to provide accurate information; what it purports to do is give you a really good search from which you can find the answer.” In contrast, ChatGPT purports to give you the answer. “That raises different questions about how responsible it is for the truth,” Srivastava says.

As for social media, Srivastava argues that ChatGPT isn’t “hosting” third party content, but producing it.

However, he cautions that there is a high bar for defamation.

“One of the essential requirements for defamation is serious harm. And I’m not sure how much serious harm ChatGPT is causing right now, even if the information is inaccurate. I don’t take what ChatGPT says too seriously. If that is generally true, how do you show serious harm?’