“We [lawyers] haven’t done our job nearly as well as we could have or should have. Because the law is not very well known at all. The law is not very accessible at all.”

The Law Society of NSW’s Future of Law and Innovation in the Profession (FLIP) Conference was held virtually on 13 October. In a sign of the times, in which remote working and digital access are becoming the norm, the online-only, immersive digital experience attracted a record crowd of more than 600 legal professionals from across Australia. Local and international experts outlined key areas of growth for the future of legal practice.

Repair the rule of law

Up to 88 per cent of legal problems never wind up on a lawyer’s desk, make it to court, or are dealt with in any official capacity.

That’s according to internationally renowned legal analyst and industry consultant Jordan Furlong, who delivered the keynote speech to the Law Society of NSW’s 2021 FLIP Conference in October. Furlong, who has spent more than 20 years studying new developments and emerging patterns in legal services told an audience of more than 200 lawyers that innovation was enabling lawyers to deliver the best legal advice in history. New tools such as artificial intelligence and online solutions are enabling law firms to deconstruct vast amounts of information much faster than human, and to mount increasingly complex class actions or corporate litigation. However, the unintended downside is most legal assistance has become too complex and expensive for everyday people to access.

Furlong qualified as a lawyer in Canada in 1994 before becoming a legal journalist then pivoting into consulting and research work, said lawyers had “overdone it on quality, at the expense of access”. This meant lawyers were largely failing in their overriding duty to protect and advance the rule of law.

The rule of law is broken, he said, and it is up to innovators of the future to fix it.

“The rule of law is something that every lawyer, no matter where you go in any country where there’s an organised legal profession, every lawyer takes seriously the concept of the rule of law,” he said.

“It’s the pillar, it’s the cornerstone of our democratic system. But if it’s so important, what are we doing as lawyers to ensure that the law is known, and it is accessible? … we [lawyers] haven’t done our job nearly as well as we could have or should have. Because the law is not very well known at all. The law is not very accessible at all.”

A study by the Law Council of Australia published in 2015 found that, over the preceding five-year period, 45,000 Australians had been forced to represent themselves in court because they were unable to qualify for legal aid. Many of them fell through the cracks between government-assisted and private legal help: earning more than the cap on income to qualify for legal aid allows, but not enough to afford a private lawyer’s advice. As former Attorney-General George Brandis said in 2012, “Unless you’re a millionaire or a pauper, the cost of going to court to protect your rights is beyond you”.

Jordan Furlong

Jordan Furlong

A paper presented by Queensland legal assistance centre LawRight to the National Access to Justice and Pro Bono Conference in 2017 found self-represented litigants who could not afford a lawyer were on the rise across Australia. These litigants are not only disadvantaged by complex or formal court practices but weigh heavily on court time and resources as they take longer to complete processes. The same paper pointed out that Australia ranked 14 in the world for civil justice out of 113 countries under the Rule of Law Index Report 2016, behind New Zealand and Singapore in the East Asia and Pacific region. Out of all factors measured in civil justice, the accessibility and affordability of the Australian justice system scored the lowest.

Furlong suggested more affordable, accessible ways of delivering legal assistance could utilise the convenience of the internet and include informal “online justice hubs”. These would be websites or apps where people could go online and present their legal problem in broad terms, and artificial intelligence systems could automate responses and direct people to where they can find information to deal with their issue.

“I would like to see a system that not only allows people to know what their rights are, but to actually obtain the remedies directly. So, if you as a worker are a victim of wage theft, you can begin a process online to have that employer investigated; to perhaps even have your wages automatically increased to receive the backpay that you’re entitled to,” he said.

“I recognise some of these things can kind of feel like radical solutions but I think we’re in the neighbourhood of wanting to try radical things … Because this [the rule of law] isn’t just a minor quibble. This isn’t just an inconvenience. This is fundamental, this is the core of who we are and what we do.”

Contracts are changing for the better

One technological innovation canvassed at the conference was the use of blockchain in creating contracts.

Blockchain, at its simplest, is a collection of information held on a digital ledger shared between all relevant parties. It paves the way for truly smart contracts because it provides a mechanism by which they can collaborate, securely share data, and make sure everyone is on exactly the same page about what was agreed to and when. This comprehensive and complete record also means automation is much more efficient and cost-effective, which means self-executing contracts are a real possibility.

Michael Bacina, a digital law expert and partner at Piper Alderman, said it was time for lawyers to “come to grips” with this technology. Merging the highly technical world of programming with end users such as lawyers and their clients is a challenge, but Bacina said there are an increasing number of low-code and no-code solutions available.

Camilla Anderson, a professor of law at the University of Western Australia, highlighted an alternative option. Comic book contracting, an idea that sees consumer contracts laid out in a simple and engaging visual format, is an idea that she said has “brought about a hunger I’ve never seen in the legal industry”.

Her interest in this area began when she was presented with the challenge of finding a way to make non-disclosure agreements comprehensible for university engineering students in Brisbane. The idea was not just to create a contract to which people would click “agree” without having read the terms, but to create something that users would actually understand so they could uphold their obligations.

Fast-forward, and comic book contracts are now being rolled out in a multitude of contexts, including employment contracts at software companies like Orocon and user agreements at financial institutions such as BankWest.

So far, she said research suggests that people who receive comic book contracts are far more likely to understand what’s going on, feel positive about the agreement, and remember what’s in it.

Subscription payment models on the rise

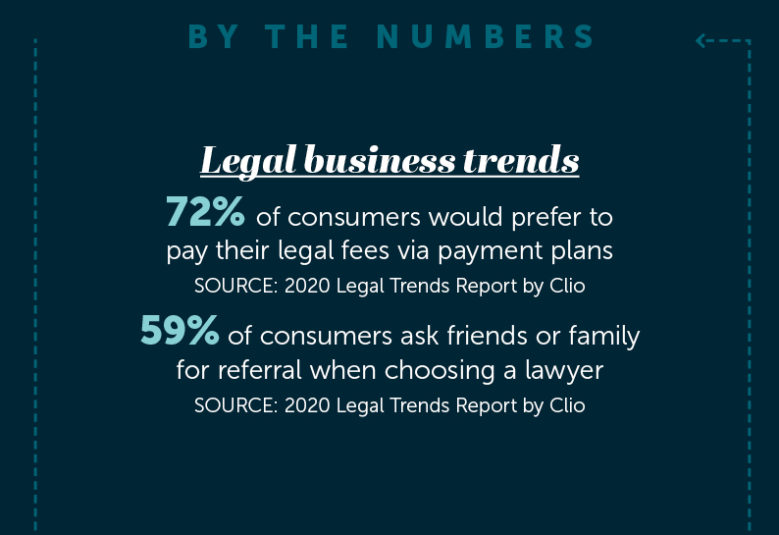

Legal service delivery is diverging significantly from traditional practice models.

“Eyeball law” is one new variation, where lawyers cast their eye over self-service documents clients have prepared and tell them how to fix them. “Horseback law” is another emerging model, in which lawyers act like a sheriff riding up on a horse to survey the landscape, make a quick assessment, and move on to the next task.

In a panel session discussing emerging legal markets at the conference, Liz Harris, Principal at Harris Cost Lawyers, said pricing is also changing significantly, with option pricing and subscription pricing emerging as the most viable alternatives to six-minute billing.

Option pricing gives clients the chance to select the services that are most important to them, Harris explained. For example, video advice instead of written advice or the level of contact they require. Subscription pricing, meanwhile, is essentially a retainer. Individuals agree to pay $X per month for the duration

of the matter, which creates certainty about their expenses so they can budget, while companies can retain law firms for an annual subscription on an “all you can eat” basis.

This model has been rolled out to great success at SprintLaw. The firm’s target market is small business and start-ups, and in its early days it conducted market research to identify what clients really needed.

The team found that lawyers were seen as too expensive, too time consuming, and too much of a headache.

Principal and co-founder Tomoyuki Hachigo, who joined Harris on the panel, said it became clear that the billable hours model could be seen to incentivise inefficiency and complexity, so SprintLaw developed a suite of standard products that are sold online with an eCommerce-style shopping experience.

This includes everyday items like setting up companies and developing shareholder agreements, created by lawyers who work online using proprietary automation software. Its services are a fraction of the cost of a traditional firm.

“We dissected the chain of legal service delivery and looked at what could be automated, or at least systemised.

The issue with most firms is that too much routine work is being done by humans,” he told conference attendees. “Anyone who’s done an all-nighter fixing formatting in a document will understand this.”

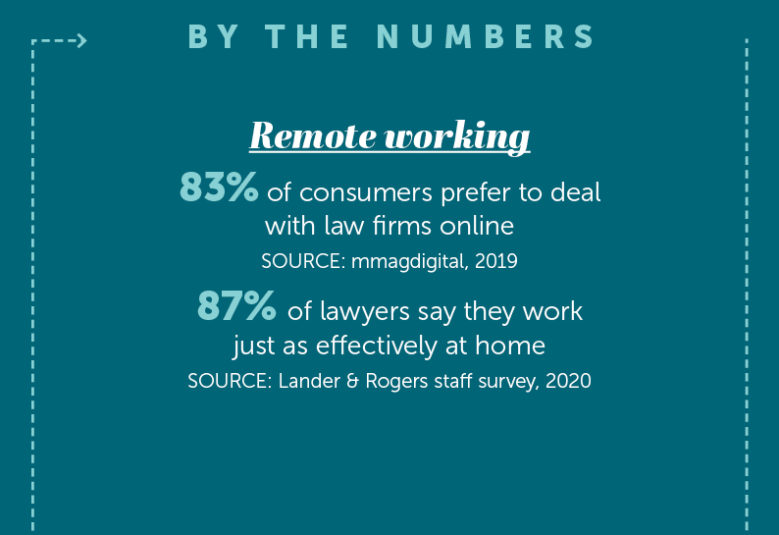

Remote hearings are here to stay

Courts provide an essential service, so shutting down during the pandemic wasn’t an option.

Conference attendees were told of how the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia, which had 120,000 listings in the last financial year, became fully virtual in just three weeks. “It was a huge challenge,” Chief Justice William Alstergren told an audience in a panel session on the future of online and remote hearings post pandemic. “The most important person in the court wasn’t the Chief Justice, but the head of the IT department.” Upgrading technology was a huge effort. The court leaned on Microsoft Teams and issued a multitude of new practice directions to speed up processes, including the filing of e-signed documents.

“It was a great learning curve for all of us,” the Chief Justice said. “Access to justice for remote and regional Australians was a great benefit. We are now a proper national court. This will reduce costs for parties and lawyers travelling to court. It provides safe access for those who may have felt unsafe being in the vicinity of the other party… this is an efficient use of judicial resources on a national basis.”

However, improvements can be made. Anne-Marie Rice, the court’s Executive Director of Dispute Resolution who sat on the panel with Chief Justice Alstergren, said assessing risk is challenging because moving online doesn’t necessarily reduce the fear or stress of a party who has experienced family violence – despite the safety of the environment. Moving the court into someone’s home can also be difficult, particularly if there are children present.

Professor Michael Legg, Director of the NSW Future of Law and Innovation in the Profession Stream, added that all participants must have adequate technology and functional bandwidth for remote hearings to be viable, which will require further investment from the government.

“There’s no point having a court that has great technology if the participants do not,” he said. “The system fails at that point.”

More research is required to evaluate the success of virtual courts from a user’s perspective. However, a survey of nearly 50 judicial officers and commissioners in NSW, conducted by the Law Society of NSW and presented in summary at the FLIP Conference, found that a clear majority supported the continued use of remote procedures for matters other than full trials or hearings. This support was conditional on the proviso that virtual courts continue to uphold the principles of open justice, procedural fairness, and impartiality.

View the conference in full, on demand, by purchasing a pass here.