Women are delaying pregnancy, and egg freezing is being promoted as an option by IVF companies, and offered as a benefit by some employers. But the process doesn't guarantee success.

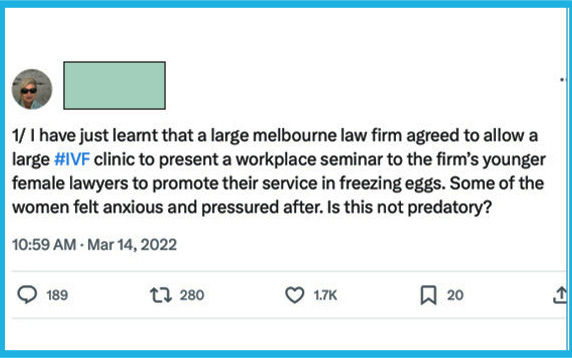

Back in March last year, when Twitter was still Twitter, one particular tweet caught my eye.

The tweet blew up, and the response was visceral. In the eyes of most who replied, the firm’s action was “utterly creepy”, “sexist”, “bizarre”, and “gross”; responses also included “sleazy”, and “outrageous and needs to be investigated”. Most people to whom I showed the tweet agreed.

By hosting a presentation for its young female employees about egg freezing, was this law firm pressuring young women to delay pregnancy? Was it encouraging them to prioritise their career above their own (potential) family? Was it asking them to delay motherhood to protect their corporate master’s bottom line?

There was something rather dystopian about it.

Young employees, especially those who are women, and especially those in traditional corporate environments, are sceptical that bosses have their best interests at heart. What counts is what’s commercial — and stories pervade of women who missed out on promotions or were treated less favourably because of a pregnancy or a request to take family leave. Most of these stories hark back to years ago but they are not easily forgotten; few people perceived the law firm’s decision to invite the IVF clinic to present a seminar on egg freezing as well intentioned.

Sentiment was similarly cynical when people heard that many large US companies and some large UK law firms cover the cost of their employees’ egg freezing. As early as 2015, Federal MP Karen Andrews decried these overseas developments as “boss-sponsored delayed motherhood”. She said companies should invest in efforts to make it easier for women to pursue both their family and career instead of encouraging women to prioritise their career and postpone having a family. In Australia, where employee-sponsored egg-freezing is almost non-existent, one commonly expressed sentiment was that these incentives send an implicit message to women: there is no excuse for starting a family on company time.

‘Companies should invest in efforts to make it easier for women to pursue both their family and career instead of encouraging women to prioritise their career and postpone having a family.’

This impression is reinforced by the relentless marketing of some IVF companies, which many view with equal distrust.

In October 2012, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine removed the ‘experimental’ label from the egg-freezing procedure. What was previously a rare procedure performed only for medical reasons gradually became widely available, including for non-medical (or ‘social’) reasons. Slowly, and then quickly, the number of IVF clinics offering egg-freezing grew, and so did their advertising budgets.

In 2017, the technology website Wired published an article titled “Hey Instagram, Don’t Tell Me When To Freeze My Eggs” — a response to the relentless targeted advertising towards 27-45-year-old women, with captions like: “When you freeze your eggs, you #freezetime. How many chances do we have to do that? [a clock emoji followed]”

In 2020, the Daily Mail reported on IVF clinics in London behaving like companies at a careers fair. One held a ‘Prosecco evening’, another an ‘egg-freezing party’ where ‘indulgent desserts’ were served at the Sheraton Grand Hotel in Mayfair, and another still offered wine and cheese at a discussion on female fertility.

On 10 November, The Sydney Morning Herald asked in an op-ed: “Do I want to freeze my eggs? Or does Instagram want me to?”

Michelle Peate is an Associate Professor at the University of Melbourne and the Program Leader for the University’s Psychological Health and Wellbeing Research Unit at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. She is an expert in reproductive health and works closely with doctors who offer egg-freezing services.

Peate says several studies have analysed IVF companies’ websites and found their material quite misleading, and the same applies to their advertising.

“At the end of the day, there are no guarantees, and freezing eggs may not result in a baby,” she says. “It’s not an easy process, there’s a rollercoaster of emotions, and it’s something big to take on”.

Each IVF cycle offers on average a 27 per cent chance of a live birth for people who froze their eggs before the age of 35, and the chances diminish with age. Marketing the procedure as ‘insurance against the biological clock’ is misleading. An insurance policy guarantees payout; egg-freezing increases one’s chances of becoming pregnant with no guarantee of success. Such deceptive promotion risks encouraging women to make a deeply personal choice without proper awareness of the costs.

Despite this, Peate is not too concerned. She says that companies are indeed profit driven, but that in her experience the doctors and other medical specialists who work at those companies — the people who meet with the patients and perform the procedures — provide them with the information they need to make an informed choice.

“Most doctors say: ‘If you want to have a baby, you should try to have a baby now’”, Peate says. “If the woman says, ‘I can’t’ or ‘it’s not the right time’, then egg freezing is an option.”

Despite the perception that many of these women say it’s not the right time because of their career, Peate says this is not supported by the evidence.

Earlier this year the Yale University anthropologist Maria Inhorn published the book

Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs. Inhorn’s research found that the majority of women froze their eggs because they were “single or in very unstable relationships with men who were unwilling to commit to them”.

“Contrary to the commonly held notion that most professional women were freezing their eggs so they could lean into their jobs”, Inhorn wrote, this was simply not the case.

‘The majority of women froze their eggs because they were single or in very unstable relationships with men who were unwilling to commit to them.’

Peate co-authored a 2017 study that found similar conclusions in Australia:

“Although there are suggestions in public and professional discourses that women ‘delay motherhood’ because of personal ambition, to achieve financial security, or for selfish reasons, there was no evidence in this research to support these assertions as reasons for [egg freezing].”

The study surveyed mostly women in their late 30s, and it is possible younger women have different motivations. But, while many more young women are freezing their eggs than was the case five years ago, and while they may be influenced partly by IVF businesses’ relentless advertising, Peate says there is no evidence that career is a strong motivator.

This certainly matches up with my (limited) experience. A close friend of mine who is currently freezing her eggs (aged somewhere between her late 20s and early 30s) is doing so because she is single, would like to have kids in the future, and is aware that fertility declines with age.

Peate refers to this as “proactive egg-freezing”, a result of “less stigma, lower prices, and more accessibility”.

I spoke to several people whose friends are undergoing the procedure and others who are considering it. Most of these women are single and unsure when they will be ready to conceive. Others are in relationships but not yet ready to conceive, and others still have already conceived but are concerned about the age at which they intend to conceive for a second or third time. Career was not a significant motivating factor for any.

In 2019, the popular American legal website Law.com published an article titled: “Busy Lawyers Are Freezing Their Eggs to Focus on Their Careers.”

The lead paragraph reads:

“Elizabeth Brown and two of her law school friends all plan to freeze their eggs in the next few years if they’re single. The 29-year-old associate at New York real estate firm Rosenberg and Estes loves her job and doesn’t want to tear herself away from it. ‘Knowing that you can freeze your eggs, it takes so much of the pressure off’, she says, adding of the need to go on a random date: ‘I’d rather go home and have a glass of wine and watch Netflix.”

The article is full of hyperbole. There is no mention of Brown’s two law school friends, nor any of the other ‘busy lawyers’ freezing their eggs to focus on their careers. The main story, at least as the headline (and many other headlines) would have us believe, is not based on the evidence.

But while Brown’s main motivation for freezing her eggs might be uncommon, her demographic — that is, a highly educated, professionally-employed single woman in her late 20s — is increasingly commonly opting for the procedure. This is the true reason for the rise of proactive, non-medical egg-freezing.

Four decades ago, Australian women on average first gave birth at 25. In 2021 that number was 29.7.

“Life circumstances mean that people are having babies later,” Peate says. Women are more likely to attend university than they used to be, more likely to undertake postgraduate courses, and more likely to be professionally employed. The age at which they are ready to have a baby is therefore much older.

‘Life circumstances mean that people are having babies later … The age at which they are ready to have a baby is therefore much older.’

The problem is that men have become less likely to do all the things that women have become more likely to do.

Jane Fisher is the Professor of Global Health at Monash University. She recently gave a speech where she described the average single, childless, unmarried woman as a highly educated professional. The average single, unmarried childless man, on the other hand, is a blue-collar worker. These people are rarely going to meet, Fisher said.

The Yale anthropologist Maria Inhorn refers to this mismatch as “the mating gap”. She says it is the main reason why women are freezing their eggs, and Peate agrees. The problem, at least for women, is the men.

Within this context (which most people who read the March 2022 tweet were not privy to or did not immediately consider), I ask Peate how she feels about employers inviting IVF clinics to present on egg-freezing.

“Every individual, if given the right information and the right tools, will make the right decision for themselves,” she says. Provided that the talk was voluntary to attend, and the speaker(s) spoke about facts, Peate thinks it might have been useful for women to learn about the availability of egg-freezing. Others who have experienced the process agreed, including one who said she wishes she had such an opportunity at a younger age:

“By the time I sought the information I needed, I had no eggs left to harvest or freeze.”

My close friend is currently in her second cycle. She says that education is crucial: “A lot of people think it’s much harder than it actually is.”

None of this excuses IVF companies that promote the procedure with the misleading and deceptive message that women can “freeze time”. Nor does it exculpate companies if their reasons for promoting or paying for egg freezing are cynical attempts to encourage staff to delay family leave absences. Employers would be far better supporting women to make choices by ensuring flexible work arrangements, increased acceptance and support, generous family leave arrangements and an environment where men too are encouraged to take time off.

But providing accurate, sensitively delivered content about egg freezing options may be one additional way to back women’s choices. Some women not yet ready to conceive may find the information and financial support beneficial.