“There are some positive benefits of anonymity, whether you’re a young LGBTQI person from a conservative family, you want those people to be able to reach out. If you’re experiencing domestic violence, you’re a whistleblower, you’re a dissident, it’s not the answer. The issue we want to solve here is the perception that you can abuse people with impunity.”

The internet has long been a place where Australians unleash their worst behaviour. Now a landmark law is set to change that.

“Social media has become a coward’s palace.” Prime Minister Scott Morrison didn’t mince words in a recent media address flagging proposed changes to social media regulations. “People can just go on there, not say who they are, destroy people’s lives, and say the most foul and offensive things to people, and do so with impunity. Now that’s not a free country, where that happens. That’s not right.”

Morrison declared people can’t just say whatever they like in normal civil discourse while hiding behind a veil of anonymity, and the same standard should apply online – people should have to identify who they are and be responsible for what they say, whether that’s vilification, harassment, bullying, or defamation.

Earlier this year, Australia enacted world-leading legislative change on cyber protections. Australia’s eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant says laws need to keep pace with rapid changes in technology and the increased risk of threats. For children spending ever-increasing time online during the pandemic, reports in online bullying threats rose by 30 per cent from 2019 to 2020.

Landmark reforms

Attorney General Michaelia Cash released the exposure draft of the Privacy Legislation Amendment (Enhancing Online Privacy and Other Measures) Bill 2021 in late October. It introduces a number of new requirements designed specifically to protect children, including a requirement that companies take “all reasonable steps” to verify a user’s age, obtain parental consent for users under the age of 16, and ensure all personal information obtained is used only in the best interests of the child.

Data and privacy protections will be dialled up across the board to promote transparency, with tougher penalties and enforcement powers available to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. The reforms could impose fines up to $10 million for serious breaches and non-compliance.

The proposed laws are largely considered to be positive. Dr Rys Farthing, Director of Children’s Policy at digital policy think tank Reset Australia says it’s unrealistic to say young people shouldn’t be on social media because their lives are digital.

“The problem is we’ve got these enormous tech platforms that are hugely exploitative and whose business models are risky for kids,” she tells LSJ. “If an awful thing goes up, why is it that Facebook’s algorithm promotes that and shows it to millions of people? We’ve always had idiots in the corner, but now we give them a microphone. It’s designed to amplify the most divisive, harmful, awful content and put that in people’s feeds, including children’s. That’s all driven by data.”

Julie Inman Grant, eSafety Commissioner

Julie Inman Grant, eSafety Commissioner

Farthing says it’s important the new legislation raises the standard of proof to require companies to demonstrate not just that harm is being avoided, but that data is being used only in the best interests of children. Australia is uniquely placed to create laws that could genuinely change the shape of the digital world. However, Farthing says there’s some important fine print. The new code is set to be co-developed by the Australian Information Commissioner and the social media industry, which she says is a concern.

“If Facebook wanted to be good with children’s data, it would be and we wouldn’t need this code,” she tells LSJ. “Australia loves a co-regulatory approach and this has worked in other industries, with good actors, to ensure those being regulated are represented. But here we’re saying hey, perpetrators of the largest breaches of children’s data rights, help us so we can protect them from you.

“We’re asking a group that is systemically harming children to help write these laws. You literally couldn’t make this up. It’s not a case of poachers becoming gamekeepers, it’s a case of poachers still being allowed to poach.”

Real-world consequences

An interesting fact is that social media causes harm. Dr Kristy Goodwin, a technology researcher and digital wellbeing expert, tells LSJ there actually isn’t a lot of research that proves causation – rather, a lot of studies indicate a significant correlation between the amount of time people spend online, particularly on social media, and poorer mental health outcomes. It’s a chicken-and-egg scenario.

“The problem in this field is because the platforms are changing so quickly, it’s hard to do any sort of experimental study that says, yes, this platform causes these adverse consequences,” she explains. That said, there is robust evidence that social media displaces other needs such as sleep or exercise, we do compare and despair when we see someone else’s glossy A-roll, and we do mirror behaviors we see online. Children are particularly vulnerable. Goodwin cites examples of young people following pseudo health advice to present to their GP with ADHD-like symptoms so they can be prescribed stimulants that suppress appetites, or mimicking potentially dangerous behaviors they’ve observed in pornography.

“On the surface level, I think [these laws] are a step forward,” she says. Goodwin has reservations about kids-only platforms that capitalise on data mining or groom them to use bigger sites in future, but she says it does provide an opportunity to educate kids about what social media is and how it works – particularly on the data side of things, where an algorithm can filter your view of the world.

“We basically toss kids in the social media world and say they’re tech savvy and they’re digital natives, but it’s like tossing them into the ocean and never giving them swimming lessons,” she says. “We’ve never explicitly talked to them about what are the ramifications of sharing a nude or semi-nude photo, or the consequences of posting something really unkind. We’ve never had those conversations.”

World leaders

Australia has taken a world-leading stance on cyber protections and it’s attracting attention overseas. The same week eSafety Commissioner Inman Grant speaks to LSJ, she has attended virtual conferences in the US and UK and announced tougher laws on image-based abuse at home. Inman Grant is not afraid to exercise her powers, if necessary, but says she prefers to channel American President Theodore Roosevelt, who famously said “speak softly and carry a big stick”.

“I don’t think we should take a sledgehammer with a nut approach,” she says on the issue of anonymity, explaining few people are truly unidentifiable online anyway.

“There are some positive benefits of anonymity, whether you’re a young LGBTQI person from a conservative family, you want those people to be able to reach out. If you’re experiencing domestic violence, you’re a whistleblower, you’re a dissident, it’s not the answer. The issue we want to solve here is the perception that you can abuse people with impunity.”

Trolls are high on sadism and low on empathy, she says. If the worst thing that happens is their accounts are suspended, they’ll just start new ones. It raises some important questions: why are people allowed to create multiple fake accounts in the first place? Where abusive accounts can’t be identified, why isn’t there a requirement to provide verifiable documentation? Why are accounts merely suspended with no other attempts to prevent recidivism? Inman Grant says these issues show why collaboration is so important. “I’m not foolish enough to think we’re going to regulate this massive industry into submission,” she says.

Fighting online trolls

Journalist Ginger Gorman, author of Troll Hunting: Inside the World of Online Hate and its Human Fallout is a key player. A story she worked on in 2010 led to a tsunami of trolling, including a death threat.

“It was like being skinned alive,” she once said in an interview. Once the online storm subsided, however, Gorman got curious and began talking to experts, tracking down her trolls, and finding out who was writing these comments and why. Unfortunately, she tells LSJ she is no longer doing interviews on this topic, but she has been a key player in advocating for change and better protection of victims.

Erin Molan, a radio and TV sports presenter, has also been a major contributor. Molan endured months of threatening and intimidating online abuse while pregnant with her daughter. Molan faced years’ worth of vile behaviour, including death threats, threats of physical violence, and threats of harm against her child. Initially, she put up with it, but the intensity increased until it affected her everyday life.

One man was eventually convicted and Molan pursued the issue all the way to Canberra. The Online Safety Act was passed in June and comes into effect in January. It contains penalties of up to $110,000 for individuals who abuse, threaten, intimidate, or bully online. The key, Molan says, is to make sure people know there are real consequences for the things they say and that they can no longer hide behind anonymous profiles.

“The old attitude of, ‘just get off social media’, doesn’t cut it anymore,” she says. “Social media is how millions of Australians stay in touch with their loved ones, run their businesses, do their jobs, stay connected during pandemics. Even if it’s not your cup of tea, you are still vulnerable to attacks.”

Platforms or publishers

The platforms versus publishers debate has also advanced protection of children. This was most notably discussed in Fairfax Media Publications v Voller, heard in the High Court of Australia in September this year. Dylan Voller is an Indigenous man who became a household name in 2016, while he was a minor, when footage of his treatment in a Northern Territory detention centre was broadcast on ABC’s Four Corners. The story sparked widespread media coverage and a torrent of hateful comments.

The High Court upheld the NSW Court of Appeal’s decision that news outlets were liable for comments made by third parties – including anonymous users – on their social media platforms, despite the fact that they hadn’t written or authorised the comments. Chief Justice Susan Kiefel, along with Justices Patrick Keane and Jacqueline Gleeson, noted in a joint judgement that because the media companies facilitated and encouraged comments from third-party users, they were to be treated as publishers. The court rejected an argument that the companies were passive victims of Facebook’s functionality.

“This is an historic step forward in achieving justice for Dylan and in protecting individuals, especially those who are in a vulnerable position, from being the subject of unmitigated social media mob attacks,” says Peter O’Brien, Principal at O’Brien Solicitors, who represented Voller. “[It] puts responsibility where it should be, on media companies with huge resources, to monitor public comments in circumstances where they know there is a strong likelihood of an individual being defamed.”

‘Making hate worse’

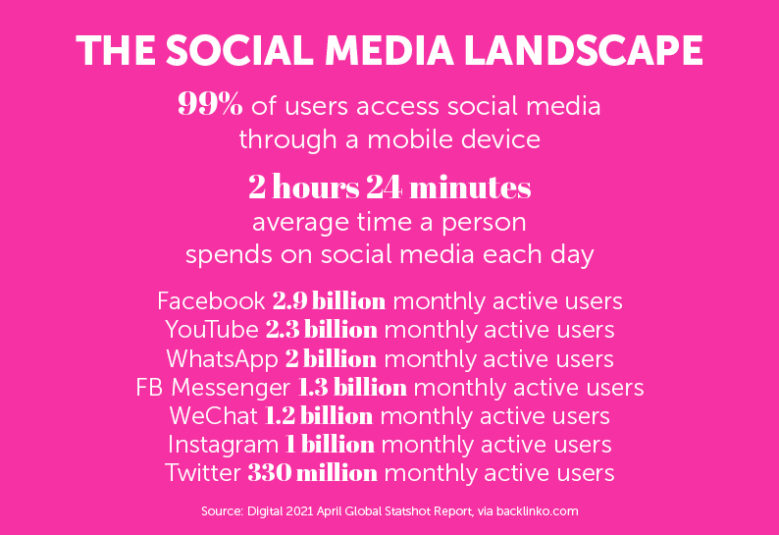

While trolls can be hunted, and perpetrators found guilty of crimes such as cyber bullying or defamation, social media companies have largely eluded regulators. They move fast and can wield enormous power, such as when Facebook (which recently rebranded its corporate arm as Meta) banned Australian news content in February, ending an impasse with the government over proposed media bargaining laws.

Meta’s business model allows users to sign up to its platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram, for free. It then mines user data to create highly targeted advertisements with a sophisticated business suite that allows sellers to adjust their content in real time to guarantee sales. Everything about it is designed to make users stay longer, scroll further, and spend more. Primarily, this means only showing content that makes them engage. This has serious ramifications, such as polarised politics, radicalised groups, and rampant misinformation. Meta’s profits rose 17 per cent to US $9.2 billion (A $12.5 billion) last quarter.

As the new bill was announced in Australia, whistleblower Frances Haugen was creating shockwaves in London. The former employee told the British Government’s Online Safety Bill committee that the social media juggernaut is “unquestionably making hate worse”. The group is consulting on a proposed law that will increase the power of Britain’s national media regulator to conduct online safety checks. Her testimony included an avalanche of confronting information, such as internal research that compared young social media users to addicts who can’t stop using the service even though they know it causes them harm.

However, in a statement to LSJ, Facebook says it supports the development of codes.

“We’ve been actively calling for privacy regulation and understand the importance of ensuring Australia’s privacy laws evolve at a comparable pace to the rate of innovation and new technology we’re experiencing today,” says Mia Garlick, Facebook’s Director of Public Policy for Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands.

“We have supported the development of international codes around young people’s data, like the UK Age Appropriate Design Code. We’re reviewing the draft Bill and discussion paper released today, and look forward to working with the Australian Government on this further.”