Open justice is crucial to maintaining community confidence in courts and the administration of justice, but it is not an absolute principle. Intense public interest in recent tragic events involving children has cast a spotlight on the complex legal restrictions surrounding publication of criminal investigations in NSW.

Media lawyer Jake Blundell is almost considering a career move into private investigation. He recalls countless times from his five years of practice in the space of open justice, where he’d don a hypothetical trench coat and deerstalker cap, hunting down defence lawyers and judges’ associates trying to find documents.

“I’ve drunk the Kool-Aid on open justice. I’ve done enough non-publication orders and cases involving children now, I truly believe deep down inside, open justice is an important concept and principle,” Blundell tells LSJ via Zoom from his office at boutique intellectual property and media law firm Banki Haddock Fiora in Sydney.

The principle of open justice is central to the rule of law and democracy. It creates transparency, public oversight and knowledge of how the legal system operates. But there is always a line that must be drawn.

Blundell acts for a range of news media organisations, including Nine Entertainment and News Corp, in relation to defamation litigation and advice, non-publication and suppression order matters. He is also involved in policy and advocacy work, including the recent defamation reforms and the current NSW Law Reform Commission review of open justice and access provisions.

The death of nine-year-old Charlise Mutten in the Blue Mountains in early January sent shockwaves across the country. The moment her stepfather Justin Stein was charged with her alleged murder, Blundell describes non-publication laws kicking in like an “artificial curtain”, halting further media reporting on the story.

When an accused person is charged with a crime involving a child in NSW, legislation prohibits publishing the child’s name, photo and any information that could identify them. This applies even when, like in the case of Charlise and many children who go missing, the name may have been plastered across television screens, social media and newspapers. The prohibition extends to children who are no longer living.

A senior available next of kin can give the media permission to identify a deceased child. However, this often results in an illogical situation where media go knocking on doors to obtain consent during a time of unthinkable grief. In Charlise’s case, a family member gave the media approval.

Under the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987, any child involved in criminal proceedings in NSW, whether as a defendant, witness, victim or otherwise peripherally attached (for example, a sibling), cannot be identified.

“It’s complex and difficult to navigate because there are so many different layers. The child might also be in care and there’s a different provision for that, or they might be involved in an adoption context and that brings its own prohibitions, and then there might be non-publication orders over the top,” Blundell explains.

There are strong arguments in favour of the prohibition, including that it reduces potential community stigma for child defendants, facilitating their rehabilitation and reintegration into society. It also protects victims and other children connected to criminal proceedings from the stigma of being associated with a crime. Principal of Rafton Family Lawyers Kate Rafton says this outweighs any argument to amend the legislation.

“The laws are working exceptionally well. I understand we are looking at legislation that perhaps has to move with the times. But when children are involved, protecting them is the focus.”

Blundell’s firm supports the rationale for prohibition but argues the “broad legislation” impinges on the principle of open justice.

“The wheels fall off our society to some extent when we keep things secret for the wrong reasons. Sunlight is the best disinfectant. Pouring sunlight on what happens in a courtroom is important so we can see if perhaps judges get it wrong or where defendants are trying to shut things up for the wrong reasons.”

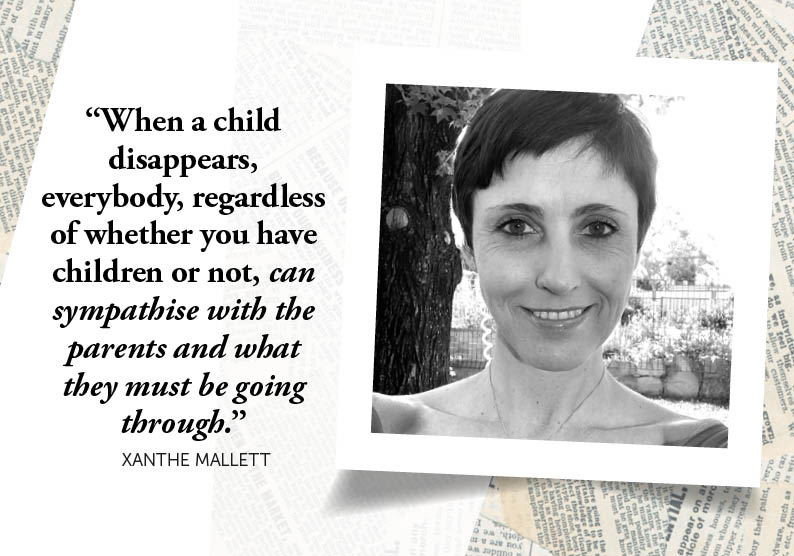

Criminologist Xanthe Mallett, an Associate Professor at the University of Newcastle, has been involved in some of the biggest missing children investigations around the world, including William Tyrell, Cleo Smith and Madeleine McCann. Mallett initially stopped answering calls about Charlise Mutten once Justin Stein was charged, because she was cautious of legal consequences.

“Everybody stopped talking about it. It prevents the truth being put out there because suddenly everybody is gagged and fearful of repercussions later in the criminal process,” Mallett tells LSJ.

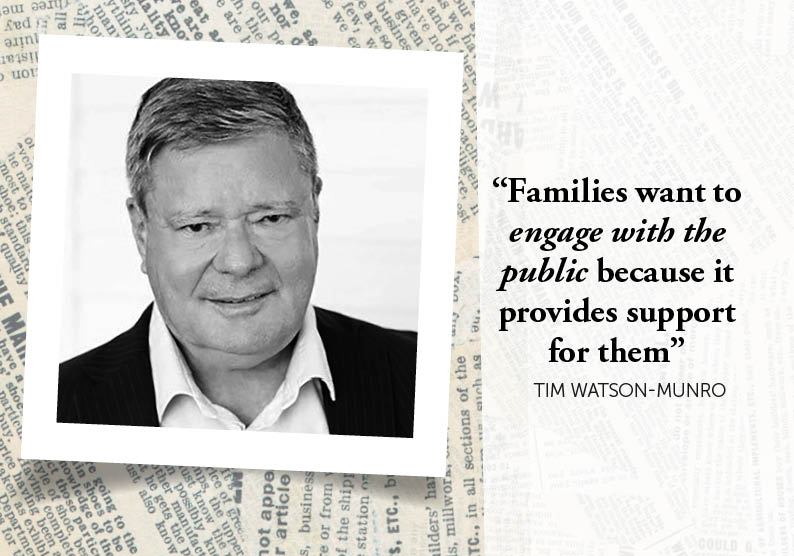

This premise is echoed by distinguished Criminal Psychologist Tim Watson-Munro, who has spent a great deal of time coming face-to-face with murderers, rapists and other heinous individuals. While Watson-Munro respects some families choice to remain anonymous, the majority of people he deals with want their stories publicised.

“If you bury the story, you bury the child and it’s like the child didn’t exist … Families want to engage with the public because it provides support for them. They feel less alienated from what’s going on and it enlivens the process,” Watson-Munro says.

Drawing a line

While the basis for open justice has multiple dimensions, it’s grounded in a need to preserve public confidence in the judiciary. Justice should not only be done but should be seen to be done and recognises the media’s significant role in facilitating that.

Mallett tells LSJ the fear induced by “totally random, situational events” involving children “that could happen anywhere” is what captivates the public. “We see children as vulnerable, as individuals that need protecting. When a child disappears, everybody, regardless of whether you have children or not, can sympathise with the parents and what they must be going through.”

The idea of protecting vulnerable groups is a key consideration of the NSW Law Reform Commission’s (LRC) current review of the laws that impact the concept of open justice. There are multiple laws that govern access to court information, non-publication and suppression orders.

Following a robust consultation process with members of the justice system, community organisations and academics, the LRC sought submissions on a draft proposal for reform in 2021. The NSW Police Force, the Law Society of NSW and the Children’s Court of NSW were among almost 100 submissions.

While various elements of open justice were addressed in these submissions, the laws relating to children implicated in criminal investigations garnered the most attention.

The information ‘black hole’

The laws in NSW against identifying children involved in criminal proceedings go further than any other Australian state or territory. It’s the only state that explicitly restricts publication of identifying a deceased child in this context. The LRC recognises this disparity and wants to make these provisions more consistent with the rest of the country, including by removing this prohibition about deceased children.

The LRC has proposed a new law allowing for publication of a deceased child’s name in NSW, so long as the publication doesn’t identify another living person whose identity is protected (for example, a sibling).

Rafton is concerned by the practical impact of such a legislative change. Rafton is a dual-Accredited Specialist in Family Law and Children’s Law, and her Parramatta team run one of the largest child care and protection practices, besides Legal Aid, in the state.

“I think we have to tread very carefully if we are looking at reforms that supposedly protect children. We can see ways that other children, like siblings, aren’t going to be protected,” Rafton tells LSJ. “There is so much access to information now with social media and the internet, so the chance of the siblings remaining anonymous won’t happen.”

Rafton’s view is supported by the Law Society of NSW’s submission to the LRC’s draft proposal. The submission expressed the view “there would be little or no public interest in publishing the identity of a deceased child in criminal proceedings” and are mindful of the privacy and cultural considerations for the family of the deceased.

Blundell and his firm Banki Haddock Fiora, support removing this polarising prohibition.

“The rationale for protecting their identities is about allowing them to rehabilitate, allowing them to reintegrate into society, you make mistakes when you are young and need a chance to move on with your life. But none of that applies, sadly, to a deceased child,” Blundell says.

“We have to keep in the back of our minds, as do the NSW Law Reform Commission, that the overarching principle is open justice. We need to balance it against important considerations like the welfare of children. There’s always a line that has to be drawn because those two things oppose each other to some extent.”

Mallett has closely examined the disappearance of William Tyrell since the three year old went missing in 2014. The picture of the little boy in the Spiderman suit is regularly splashed across the media when there are developments or leads in the case.

Mallett tells LSJ she is aware, because of the current legislation in NSW, that if anyone is ever charged, the entire public-facing operation will stop.

“There will be this black hole of information in a case that’s been high profile. The whole media and commentary will shut down and people will make up hypotheses which can end up being a problem later if it goes to trial.”

In the recent case of Charlise Mutten, Mallett argues by taking away the ability to say her name, it removes her from the situation entirely.

“To me that seems more disrespectful because suddenly you’re not allowed to talk about that little girl anymore, what went wrong and the opportunities to step in and prevent it from happening.”

Opposing forces

The prevalence of new media has disrupted the status quo. Members of the public share names or images of missing children on social media without awareness of the legalities, challenging the courts’ practical ability to supress information.

Police and investigative authorities rely on the public for information, especially in missing children cases and their names and photos are often published on official channels.

Another LRC proposal is to extend the existing statutory prohibition on identifying children connected to criminal proceedings to cover the entire period of investigation before charges are laid. This was inspired by similar legislation in the United Kingdom. The LRC has received backing for this proposition, and the NSW Police Force says it “supports this amendment in principle”.

Blundell argues it will create more problems than it solves. “It’s going to hamstring police. There will be an exception if the safety or wellbeing of the person is in danger but who makes that call? There are criminal sanctions attached to breaching these things. Do the police want to run the risk of committing a criminal offence?”

“Our act is the broadest in Australia already. To make it broader, by now extending it to investigations, creates another level of complexity for journalists to try and work out. It’s going to have a chilling effect.”

Watson-Munro deals with all jurisdictions in Australia through his work and wants to see the laws in NSW brought into line with the rest of the country. He says the current discrepancies between states is counter-intuitive, and this proposal to put a “blanket ban” on investigations will exacerbate that.

“It seems to be a misguided attempt to protect people, but they may be paradoxically interfering with the investigation and the natural progression of solving a crime and justice. I think it’s potentially very destructive and dangerous.

“How do you define the beginning and the end of the investigation? The end of the investigation might be a needless tragedy because people weren’t engaged on the way through,” Watson-Munro tells LSJ.

Greater accessibility

Public awareness of these current prohibitions is low. The NSW LRC wants to improve how open justice, and breaches of it, is monitored and penalised. But the greatest barrier is the current state of the legislation.

The LRC outlines in their proposal that statutory offences are not clearly and consistently framed, there is no central agency to investigate and enforce violations and investigation of breaches can be difficult and time-consuming.

Jake Blundell has extensive experience with the latter. The LRC has proposed a register of non-publication, suppression and closed court orders that is searchable by journalists, legal representatives of news media organisations, researchers and publishers. This, Blundell tells LSJ, will be a game-changer.

“I’ve had District Court judges who have said they were down in the archives themselves digging around in boxes on the weekend trying to find documents going to orders that might have been made,” Blundell says.

Mallett teaches her criminology students at Newcastle University to always keep an open mind, especially when dealing with cases involving children. Mallett says on an academic level, the unpredictable nature of crime is what lights her fire.

“You can look at all the cases you’ve ever looked at to make educated guesses about what’s happened and why, who may be involved. Then, something like Cleo Smith happens and it blows everything out of the water.”

“I work with victims of crime a lot and the families left behind from missing persons and murder cases that haven’t been solved. For the public, it’s a sound bite on the news and its gone. But for the families, 10, 20, 30, 40 years later, it’s just as raw as the day it happened. Having conversations in the media that are respectful, victim-focused and keep the attention off the offender and giving the victims the autonomy in that space is really important to me.”

The LRC hopes to transmit its final report on open justice to the Attorney General this year. But there are calls to make the legislation more accessible and easier to digest for the wider community.

“Legislation should be able to be understood by everybody. It governs everybody’s actions; it shouldn’t just be the realm of lawyers to analyse,” Blundell says.

Mallett agrees: “How many people in the public genuinely knew that [there was a submission process]? Charlise Mutten’s grandmother might have thoughts on this now, and people who have been directly impacted. But does she know the laws might be changed? I doubt it, and those are the people it’s going to impact.”