Just months after the ALRC finished its extensive inquiry into the Australian family law system, Prime Minister Scott Morrison has announced a new inquiry led by a joint select committee. Many lawyers say it will simply add to the cycle of frustration and fatigue.

A multitude of inquiries have sought answers to Australia’s family law woes. The most recent was completed in April, when the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) handed down a 574-page report with 60 recommendations. In the course of its investigation, the ALRC considered the findings of at least 13 other inquiries that investigated family law, as well as 31 reports exposing systemic issues on topics ranging from surrogacy to child support.

Thirty-eight of them have been handed down in the last 20 years.

Most tell a familiar story: Australia’s family courts are drowning under enormous caseloads. The system is overwhelmed and under-resourced. The intense stress arising from long delays and burgeoning costs is a symptom of a system failing to serve those who need it most.

The circle of inquiry shows no sign of resolving any time soon. In fact, the government is yet to respond to the findings of the ALRC report, even though it was specifically commissioned by the Attorney General back in 2017 and has been formally tabled in Parliament.

Instead, Prime Minister Scott Morrison recently announced another inquiry into the family law system, to be co-chaired by Liberal MP Kevin Andrews and One Nation leader Pauline Hanson. The terms are yet to be defined, but it’s expected that family violence and parental rights will be key discussion points.

“There are blokes who are victims, there are women who are victims, and most tragically there are children who are victims. It’s just an awful human mess,” Morrison said in September.

“The reason to do a joint select committee is to able to truly listen to the stories and evidence it can bring forward in a sensible, apartisan way.”

Systemic failures

The legal community has had a mixed response to the announcement. While it is widely accepted that the system desperately needs change, no-one can agree how to take action.

“Systemic failures plague the system. Children and victims of family violence are slipping through the cracks. This cannot continue,” said Arthur Moses SC, President of the Law Council of Australia, in a statement welcoming the announcement of the joint parliamentary inquiry.

“Countless reports have set out the technical recommendations for parts of the system. Yet nothing has changed. Why? Because policy-makers have not stepped back to see the forest, not the trees. We all know too well the problems. We need to get agreement among our politicians on the solutions.”

Meanwhile, Law Society of NSW President Elizabeth Espinosa is calling for urgent action. She wants the committee to consider the ALRC’s recommendations and address key issues immediately.

“Everyone who works in the family law system is only too aware of the significant financial and emotional stresses on families caught up in lengthy court disputes, the consequences of which can have a life-long impact on physical and mental health, housing, careers and future relationships,” she says.

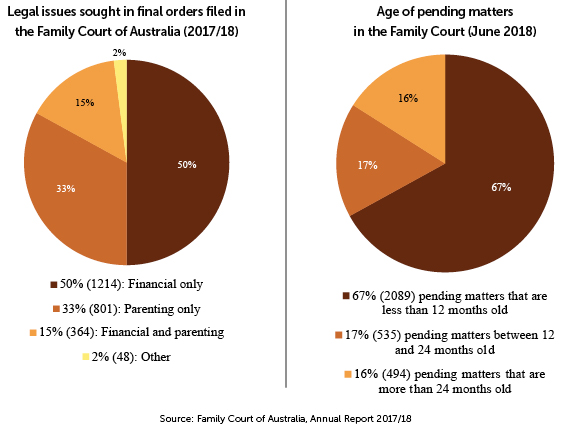

Indeed, it can take years to navigate the family law system from beginning to end. Family Court of Australia figures from 2018 show that 17 per cent of pending matters have been in the court system longer than one year, while a further 16 per cent of cases have been pending for at least two. Practitioners tell LSJ that some of these may languish in the system for up to three or four years.

Ongoing gender war

The balance of men’s and women’s rights is unique to family law. In addition to the intensely emotional nature of the subject matter, it’s a key reason why conflicts are so drawn-out and acrimonious.

Diana Bryant AO QC served as the inaugural Chief Federal Magistrate of the Federal Magistrates’ Court of Australia, as the Federal Circuit Court was previously known, and as Chief Justice of the Family Court of Australia from 2004 until 2017. She tells LSJ the most important thing is that the system puts the rights of children first.

“We have in Australia an ongoing gender war which needs to stop,” she says. “It abates for a while and then breaks out again, the pendulum goes from gender to gender over the years. I don’t know why; I expect it’s reflective of our political leadership. One group gets a champion, and then another. Cycle after cycle, it doesn’t seem to get any better. The reality is that children have rights – not just their parents.”

Former Justice Bryant also expressed concerns over recent comments Senator Hanson made to the media in which she alleged that some women were lying about domestic violence events in order to win custody battles. The remarks, made on ABC radio, caused widespread concern.

“[This inquiry] could mean we won’t see the changes from the ALRC reports that perhaps we ought to. I think it’s obviously unfortunate that Senator Hanson made the comments she did and communicated that she clearly has an agenda, because that raises expectations, and if those are not met, it puts the government in a difficult position. You end up making bad laws under pressure.”

Zoe Durand is a nationally accredited mediator, family dispute resolution practitioner and lawyer. Last year, she published a book called Inside Family Law, which features a series of interviews with judges, barristers and solicitors, in a bid to demystify family law.

“I do understand why people want to question the family law process, but I’m wondering if we’re going about it in the right way if we keep having more inquiries – especially when [the government is] yet to respond to the last one, which cost a lot of time, effort and money. It’s like Groundhog Day,” she says.

On the question of gender, she pauses.

“When I speak to women, they say [the system is] biased against women; when I speak to men, they say it’s biased against men. They’re both able to give reasons. Is it possible it can be more difficult for men in one way and women in another way, because of societal expectations about how we think men and women should behave? Both sides are suffering, but differently.”

Key issues for women

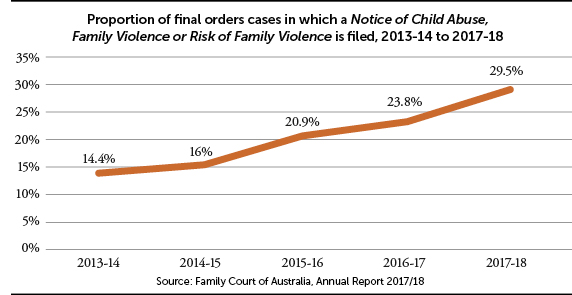

Family violence affects women at a much higher rate than men. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, one in six women and one in 16 men have experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of a current or previous partner.

Hayley Foster, CEO of Women’s Safety NSW, is advocating for immediate change.

She says a standard risk assessment process for family violence, improved information-sharing amongst family service providers, and specialist case management for high-risk matters are essential changes that will get all stakeholders on the same page, and help cases resolve more efficiently.

Her reasoning is that faster resolution will ultimately increase safety for parties.

Foster explains that a key problem with recurring inquiries is that the process can be traumatising and fatiguing for abuse survivors who share their stories again and again. Additionally, she says there is a fear women with legitimate experiences of violence could be painted as liars in a public setting.

“Anyone who has experienced violence or abuse in a domestic setting has been disbelieved many times before, and that has a significant impact. It’s not an illegitimate fear,” she says.

“What we really want to see are better functioning courts. That will help everyone, including the fathers. We don’t want to hold equality back or take away their rights, we just want to see safety first.”

The stress that comes from the delays, the costs, the anxiety and most particularly the uncertainty of outcome – and the timing of that outcome – means everyone is under pressure.

Justin Dowd, Director, Watts McCray

Key issues for men

James Stokes is the Director of Men’s Legal Service, a not-for-profit firm at Underwood in Brisbane, and is welcoming the inquiry. He tells LSJ the biggest issues facing men are custody of children and access to justice and says the family law system is in desperate need of attention.

“If you do have an obstructive spouse, and you’re not a custodial parent, it can take a long time to get the matter resolved – during which time you’re disadvantaged because that becomes the new normal,” he says.

“Our clients might be on $60,000-$80,000 a year, but once they start paying $5,000-$10,000 a month in legal fees [at traditional firms], it becomes an issue. If you’re in a situation where, rightly or wrongly, they consider the children are being withheld, there is no legal system for them to get access outside the courts.”

Stokes also raises family violence and safety considerations. The trouble with protective orders, he says, is that it’s not uncommon for parties to accidentally breach them because they haven’t fully understood the terms. This can cause further delays and be detrimental as matters progress.

“If you take the gendered element out of it and just look at the problems being faced – some issues affect men more; some affect women more – there are a lot of measures that could be put into place,” he says.

“The sooner it’s over, the sooner the healing can begin and the normalisation of the new relationship between the parties and the kids.”

The biggest hurdle

Family law issues are much more complex than people might think, but there are critical practical issues that must be addressed before the courts can delve into questions of gender, says Justin Dowd, who has been a director at family law firm Watts McCray for 20 years and a solicitor for 40.

“The stress that comes from the delays, the costs, the anxiety and most particularly the uncertainty of outcome – and the timing of that outcome – means everyone is under pressure. People going through a divorce, a separation … it’s hard enough as it is without dealing with all the legal stuff,” he says.

“[This inquiry] is going to be a polarised debate about family violence that’s not actually going to improve the family law system, because there are so many things that need to be dealt with first.”

The most pressing issue facing the family law system is a lack of court resources.

“It’s been under-funded for a long time, not least because there have been two different courts competing for resources. The whole system has been short-changed,” says former Justice Bryant, referring to both the Family Court and the Federal Circuit Court.

“This under-funding is reflected in the significant delays. That’s totally unacceptable and it puts families at risk. We need more resources, more judges. We need to get the government to understand that even if you don’t appoint judges, appointing more family consultants and more registrars will help.

“They have huge dockets they can’t really give attention to, but if you have more resources, you can do more work along the way to get people to settle at an earlier stage. You don’t want people settling for the wrong reasons just because they’ve had enough.”

In 2017-18, 2,427 final order applications and 3,400 interim order applications were filed in the Family Court. Meanwhile, 17,241 final order applications and 21,710 interim order applications were filed in the Federal Circuit Court over the same time period. The workload is relentless.

Kate Riskalla, a partner and accredited family law specialist at Robertson Saxton Osborne, tells LSJ she often spends more time thinking about the system than the law itself.

“I definitely have sympathy for the judges – I mean that respectfully, it’s a very hard job in very hard circumstances. In Sydney, they have hundreds of cases at any given time, and since there are only 365 days in a year, the workload is insurmountable. It’s relentless.”

Alternative approaches

Aside from increased funding, another solution is alternative dispute resolution.

The ALRC report noted that family dispute resolution is currently the most popular pathway for parenting matters. The 2006 reforms, which made attempts at dispute resolution compulsory (with exceptions), have stimulated a 25 per cent drop in the number of parenting matters that reach court.

“It’s extremely rare that you can’t get at least a partial outcome,” says Durand, who runs Mediation Answers. “Say we’ve got three issues to talk through – parenting matters, property matters, interim issues – even if we just resolve some of them, we narrow the gap.

“Sometimes you can reach conclusion and sign consent orders. Sometimes you might have partial or interim agreement. Ultimately, it’s about progression.”

In 2017-18, 58 per cent of the 10,066 applications for final parenting orders made in the family courts were settled without judicial determination. The ALRC report indicated the settlement rate for financial and property matters is higher again, at 80 per cent of the 7,386 matters filed. The numbers indicate that this has been a very good thing for courts, lawyers and clients.

A broader issue for society

Janis Donnelly-Coode is a solicitor at Novus Law Group in Sydney’s western suburbs. For the past seven years she’s been running sessions to teach local students about respectful relationships.

She believes we need to accept that family violence is not just a legal problem, but a societal one.

“The average person in our society has a pretty shallow view about what is and is not domestic violence, and what does and does not cause it. It’s a very complex problem,” she explains.

“One of the commonalities in abusive relationships is a lack of respect – not just romantically, but in work relationships, family relationships, with friends. It’s a conversation we need to be having.”

Donnelly-Coode knows that statistical change won’t happen overnight, but she says if everyone has a frame of reference and uses the same language, it will help society move forward.

“Divorce isn’t pretty. No-one gets married expecting to get divorced, that’s not how it works. It’s one of the most stressful experiences of people’s lives – with or without domestic violence,” she says.

“We can make laws, we can make rules, but we can’t make people communicate.”