5 March marks the International Day for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Awareness, LSJ speaks to Melissa Parke, Executive Director of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) about the reasons Australia has not signed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), and what the consequences may be.

Australia has signed up to both the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and the 1986 Rarotonga Treaty. Yet despite assurances from the Albanese government that it would do so, Australia has not signed and ratified the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

Further, Australia and Japan jointly established the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI) in July 2010 with the key objective of promoting the implementation of this action plan. The NPDI is a cross-regional group of 12 countries: Australia, Canada, Chile, Germany, Japan, Mexico, Nigeria, the Netherlands, the Philippines, Poland, Türkiye and the United Arab Emirates.

The TPNW prohibits the manufacture, production or acquisition of nuclear explosive devices; research and development relating to their manufacture or production; the possession or control over such devices; the stationing of nuclear explosive devices in their territories; and testing of nuclear devices.

The NPT requires nuclear weapon states who are signatories of the treaty (US, Britain, China, Russia and France) not to pass nuclear weapons or technology to non-nuclear weapons states. However, as per Article 4 of the treaty, this requirement specifies a prohibition on the use of nuclear materials associated with nuclear weapons. It makes allowances for the provision of nuclear materials for “peaceful purposes” which is how Australia is defending its AUKUS plan to purchase, build and maintain a fleet of nuclear submarines.

Progress and promises falter

At the United Nations in October 2022, Australia ended a 5-year period of voting in opposition to the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) in favour of abstaining to vote, so it was far from endorsing the treaty which ensures a framework of verification and enforcement of the NPT.

Australia’s fence-sitting position had mixed responses. While Indonesia and New Zealand governments praised the end to Australia’s opposition to the treaty, the US claimed that Australia was risking the existing and prospective defence agreements, deemed necessary “for international peace and security”.

The choice to abstain aligned with the Labor Party’s commitment to sign and ratify the TPNW during its national conference in 2018, a resolution made by Anthony Albanese that he reasserted in 2021. When Labor parliamentarian Susan Templeman attended the first meeting of states parties to the TPNW in June 2022, she was galvanised by a joint letter from former Australian ambassadors and high commissioners to the prime minister in support of signing and ratifying the TPNW.

Nevertheless, Australia has not ratified the treaty based on its excuse that the government is continuing to consult with partners and stakeholders while it examines and gathers information. It is a position that jars with the many organisations and political parties advocating for ratification of the TPNW. These include the Australian Red Cross, the Australian Medical Association, the Australian Council of Trade Unions, and more than 40 councils from cities including Brisbane, Canberra, Hobart, Melbourne, and Sydney.

China claimed that the AUKUS deal will eventuate in “the illegal transfer of nuclear weapon materials, making it essentially an act of nuclear proliferation”

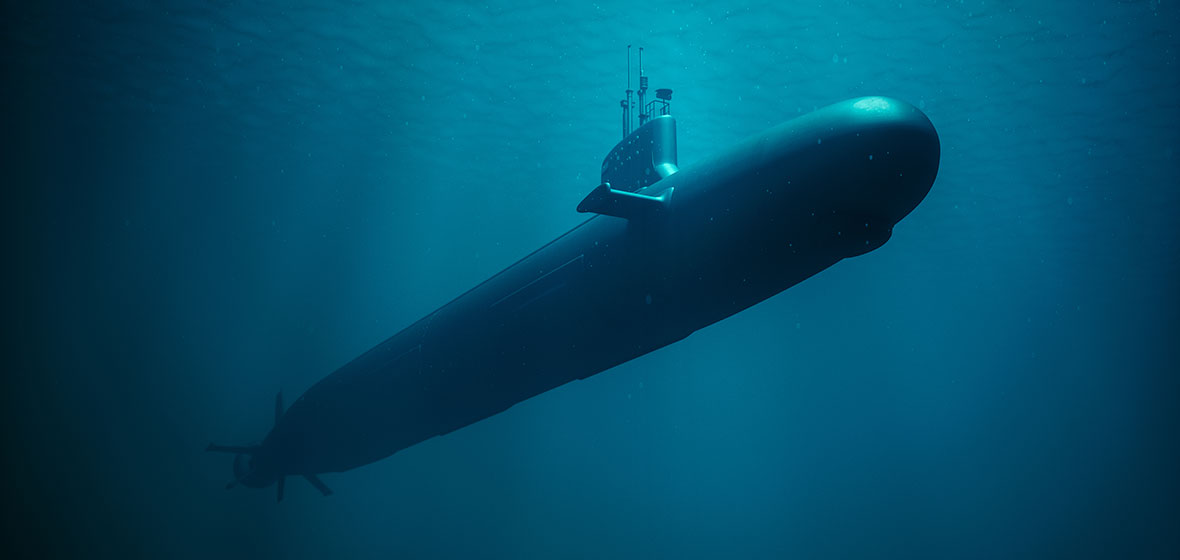

The AUKUS plan for nuclear submarines

In February 2023, consequent to the AUKUS plan, Australia announced the deal to purchase three Virginia-class nuclear-powered, conventionally-armed submarines before the 2030s, and plans for Australia to build nuclear-powered submarines aided by US nuclear technology by the 2050s. Australia is the first party to the NPT to own and maintain nuclear submarines beyond the weapons states (US, Russia, China, Britain and France).

The AUKUS plan had already raised alarm both domestically and within the Pacific region. China claimed that the AUKUS deal will eventuate in “the illegal transfer of nuclear weapon materials, making it essentially an act of nuclear proliferation” in a position paper sent to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) member states during the September 2022 quarterly meeting of the IAEA’s 35-nation Board of Governors.

Australia responded that the fuel in its nuclear submarines could not be used to make nuclear weapons, since this would require chemical processing facilities that Australia was unable and unwilling to accommodate. Australia has defended its position on owning nuclear submarines as a party to the NPT based on an allowance for marine nuclear propulsion where necessary arrangements are made with the IAEA.

The 1986 Rarotonga Treaty which Australia is party to requires that no “nuclear explosive devices” can enter the nuclear-free zone within the South Pacific. It specifies limitations on the distribution and acquisition of nuclear fissile material. While New Zealand does not allow vessels carrying nuclear weapons to visit its ports, Australia does allow this, which the treaty has provisions for.

ICAN perspective

Established in 2007, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) represents a coalition of non-governmental organisations that advocate for adherence to the United Nations nuclear weapon ban treaty.

In September 2023, Melissa Parke commenced her role as Executive Director. Parke is a former United Nations legal expert and Australian government minister with over two decades of experience in international development, human rights, law, and politics. In her capacity as an ICAN Australia ambassador, she campaigned for Australia to ratify the TPNW. She was the former Minister for International Development and former Member of Parliament for the Labor Party for Fremantle between 2007 and 2016. Prior to entering parliament, Parke served as an international lawyer with the United Nations in Kosovo, Gaza, New York and Lebanon between 1999 and 2007.

Parke says, “I first got involved with nuclear issues when I joined a campaign to stop the international nuclear waste dump being established in Western Australia by a company called Pangea Resources.”

She is referring to a high-level radioactive waste repository proposed in 1998 by Pangea Resources Australia Pty Ltd, the joint venture of British Nuclear Fuels Limited, Golder Associates and Swiss radioactive waste management entity Nagra. The proposal was ultimately rejected, and two parliamentary acts were subsequently introduced: Western Australia’s Nuclear Waste Storage (Prohibition) Act 1999, and South Australia’s Nuclear Waste Storage Facility (Prohibition) Act 2000.

Parke was also inspired by former Australian MP and Deputy Labor Leader Tom Uren AO.

She says, “He’d been a prisoner of war in Japan during the Second World War, and he witnessed the atomic bomb being dropped on Nagasaki, because the POW camp was just outside Nagasaki. He came home and spent the rest of his life campaigning for peace and nuclear disarmament. And ultimately, I’ve spent my life campaigning on human rights issues and environmental issues, and I think there’s no greater injustice against humanity and the planet than nuclear weapons.”

Parke has just returned to her Geneva base from a trip to Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Tokyo.

“It was quite extraordinary to be in the only places where nuclear weapons were used in cities during conflict. While I was working for the UN, based in Kosovo, Gaza, Lebanon and Cypress in 2002, I saw the impact of war on civilians. I attended a commemoration for Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the Gaza Harbour and saw hundreds of Palestinian children who’d made paper boats that they lit alight and set afloat on the harbour. These children in a conflict zone were remembering children in another time and place that had been bombed. I’m really reflecting on that now.”

During the trip, Parke says, “The elderly Japanese survivors of nuclear weapons that I met told me about watching their family and friends die in front of them, and they experienced radiation sickness. These were the people who had been remembered by the children of Gaza in 2002. These elderly Japanese people were organising nightly rallies in support of Gaza. It’s reflective of the fact that nuclear weapons have an impact across space and time.”

A small nuclear war would not only kill 120 million people but send soot into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and causing mass crop failure that would result in starvation for up to 2 billion people. That’s just a small nuclear war.

Australia’s nuclear future

Parke says, “I think Australia can play a really important role, as it has in the past, in nuclear disarmament. It’s in a key position to do so. Australia already has a legal obligation in the 1968 NPT to never acquire nuclear weapons and it’s also accepted the Treaty of Rarotonga requirement never to allow another state to carry nuclear weapons into this territory. The 2017 TPNW contains broader prohibitions. Most notably, upon becoming a party Australia would need to refrain from allowing any other state to use, threaten to use, or possess nuclear weapons.”

She continues, “In order to comply with this prohibition, changes would be needed to Australia’s military cooperation arrangements with the United States, because the US possesses more than 5000 nuclear weapons. For example, the joint US-Australian military and intelligence facility at Pine Gap near Alice Springs could not be used for nuclear targeting and Australia could not allow visits to its territory by US aircraft or submarines carrying nuclear weapons. In addition, Australia could not continue to claim protection from the so-called US ‘nuclear umbrella’ because maintaining a military doctrine that envisages the possible use of nuclear weapons by the US on its behalf would be incompatible with the TPNW. Extended nuclear deterrence, which is the doctrine that Australia relies upon, is simply the threat to have the United States murder millions of innocent people indiscriminately. So, that’s not acceptable legally, or morally. In addition to the fact that it’s very unlikely that the United States would sacrifice Los Angeles for Sydney.”

Further, Australia would be required to provide financial assistance to victims of past nuclear testing if it signed the TPNW.

“There are no obstacles to Australia signing the TPNW,” states Parkes. “It was negotiated in 2017, adopted with the support of 122 countries. The US vocally discouraged allies from joining the treaty under the Trump administration, and while Biden has maintained opposition, the US is no longer telling countries not to sign it, according to US state department.”

She adds, “Nothing in ANZUS would prevent Australia becoming party to the treaty, nor would AUKUS. We’ve raised proliferation concerns relating to AUKUS but it doesn’t conflict with TPNW as long as nuclear powered submarines never carry weapons or contribute to the making of such weapons.”

As far as threatening the US alliance with Australia, Parke says that history would suggest that our two nations can have contrasting attitudes to treaties on weapons without damage.

“We have already ratified the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and the 1997 Ottawa Treaty which prohibits anti-personnel mines. We don’t have to mirror the US.”

Parke says, “Australia shouldn’t become an outlier. Anthony Albanese routinely expressed his support, along with most Labor MPs who support the TPNW, and so we think now is the time for action on that promise. Australia’s joined treaties prohibiting other inhumane chemical and biological weapons, so it just makes sense to join the treaty that prohibits the most destructive, insidious weapons of all. A nuclear war can never be won and should never be fought.”

Parke refers to a study reported in Nature Journal in August 2022.

“A small nuclear war would not only kill 120 million people but send soot into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and causing mass crop failure that would result in starvation for up to 2 billion people. That’s just a small nuclear war. A major war, such as between Russia and the US, could kill five and a half billion people through nuclear starvation during winter. A TPNW is the only place where any disarmament action is happening, the only glimmer of light in a dark, strategic security environment. Australia needs to be part of this democratic shift.”

The broad ratification of the TPNW has already resulted in divestment of around a trillion dollars from the nuclear weapons industry. Large pension funds and other major investors have opted out, “which makes a big difference” explains Parke. “New York City, for example, has joined ICAN Cities Appeal along with Paris, Los Angeles, Sydney, Geneva and others to take actions to divest from nuclear weapons.”

Divestment is a powerful tool, but so is pressure from the public and raised awareness of the TPNW via media and social media has had an impact.

“The TPNW, like other conventions, is about prohibiting weapons that can’t be used in any way consistent with international law or morality. Once banned, those weapons become delegitimised. We can’t force nuclear states to disarm but we can make it legally and morally unacceptable and those countries may, in time, choose to disarm for the sake of its international reputation. Even though the US ultimately provided Ukraine with cluster munitions, there was a lot of media and protestation about it. The US could still do that, but not without cost to its reputation. That’s the intention of the treaty.”

Parke concludes that nuclear weapons are a recipe for “indiscriminate mass murder, and that’s simply unacceptable. Over the decades, there have been more than 60 accidents that we know of as the result of mistakes. These nuclear near-misses over the decades could have ended in global catastrophe, which were averted through nothing other than dumb luck, and luck is not a strategy.”

She says, “It’s an existential risk to the planet, and any risk above zero is unacceptable. The more they exist, the more chance they’ll be used. Ratifying the TPNW is in the best interest of the collective security of humankind and the environment.”