A new way of providing pathways to legal services: an Australian-first antiracism chatbot that aims to help people heal from the mental health effects of racism and improve access to justice.

Priyanka Ashraf was shopping for groceries when she was racially abused. It was early in 2020, when Australia was only beginning to understand the significance of COVID-19, that a fellow customer told her to go back to where she came from – and to take the virus with her.

“I still remember my heart was beating so fast. It was very confronting,” Ashraf reflects. “I started experiencing emotional somersaults. First of all you’re in shock, then you’re experiencing shame, then anger and fear, all in less than 30 seconds.”

When the lawyer-turned-entrepreneur decided to call out the racist behaviour, her offender denied the situation and called Ashraf crazy. “The lasting impact of racism on mental health is grossly underestimated and undermined as we are regularly gaslit into thinking that we are imagining things when faced with racism,” she says. “There are so many different thoughts and emotions going through your mind, so it’s really critical that during that time you can process it and know that what you’re going through is real.”

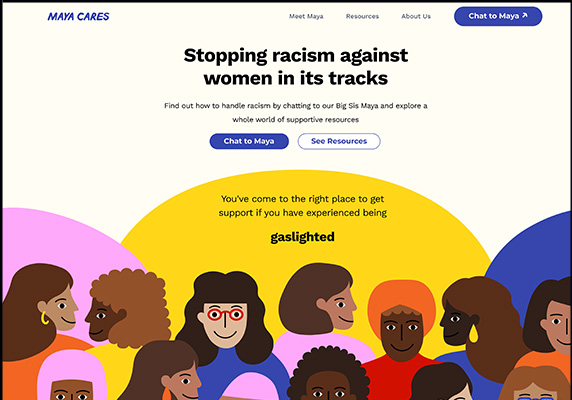

Working to address this problem is Maya Cares, an innovative mental health chatbot and digital platform that supports people to heal from and report instances of racism. It’s the brainchild of creative consultancy The Creative Co-Operative, Australia’s first start-up social enterprise that is entirely owned, led and operated by migrant women of colour, including founder and director Ashraf.

The launch of Maya Cares last month was two years in the making – and for good reason. The first-of-its-kind resource was designed by and for First Nations, Black and Women of Colour (FNBWoC) and involved consulting over 250 community members with lived experience of racism in order to best promote and protect cultural safety. The initiative has received support from the Victorian Department of Families, Fairness and Housing and Humanitech, an Australian Red Cross program focused on the role of technology in meeting humanitarian need.

Maya Cares comprises two key components: the chatbot – called Maya – provides in-time support and validation to help users address their initial response to racism, while the digital library offers more than 100 resources and services from the broader mental health community.

Depending on their individual needs, users can choose to follow three different pathways to understand, process and report racism. “Equip” provides connections to sources of support, including directories of culturally appropriate counsellors, self-care tips and information about legal rights. “Empower” dives into learning, with links to racial literacy podcasts, stories from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and creative works by culturally, racially and gender-diverse artists. Finally, “act” focuses on practical ways to take action and advocate, from platforms to report racism to social justice training and leadership programs.

“We asked people in our communities what they needed to heal from racial trauma, whether that be in the workplace, education settings or even socially,” Ashraf continues. “We heard loud and clear the dire need for access to mental health support services that are specifically catered to supporting the experiences of racial trauma of FNBWoC. Maya Cares provides a safe haven and community support, and for FNBWoC to have their voices heard and experiences validated.”

‘We heard loud and clear the dire need for access to mental health support services that are specifically catered to supporting the experiences of racial trauma.’

The FNBWoC community is disproportionately impacted by issues of discrimination and racism, which are increasingly burdensome to the Australian economy. Racial discrimination cost an estimated $44.9 billion, or 3.6 per cent of Australia’s GDP, every year in the decade between 2001 and 2011, according to landmark research conducted by Deakin University. Meanwhile, the 2021 COVID-19 Racism Incident Report, a collaboration between the Asian Australian Alliance and Osmond Chiu, a research fellow at think tank Per Capita, found women bore the brunt of heightened racial abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A new legal pathway

A critical offering of Maya Cares is the ability for individuals to report incidents of racism to relevant authorities, including the Australian Human Rights Commission, Islamophobia Register and First Nations Racism Register. This was an intentional inclusion to help remove barriers to reporting that currently exist for FNBWoC, including self-doubt, shame, fear and difficulty understanding legal processes.

“When I experienced racism, as someone who was admitted to practice as a solicitor, I had no idea how to report it,” Ashraf reflects. “So if someone doesn’t come from a legal background, they would have, I assume, even less access to that knowledge.”

As an independent third party, Maya Cares occupies a unique position separate from the government, police and even lawyers, affording the platform an increased level of trust among migrants and refugees who may be sceptical of authorities. “Users themselves have stated that Maya Cares feels like a big sister. That’s who you’re going to confide in. That’s what’s going to make it feel easier, psychologically safer, to disclose what happened to you,” Ashraf says.

While Maya Cares does not offer legal representation, by providing a direct pathway to the justice system through its reporting capabilities, the digital platform intersects with the legal sector. Ultimately, it aims to create a network of pro bono lawyers and community legal services that will support its users to make complaints.

The legal services monopoly

Dr Scarlet Wilcock, a lawyer, researcher and academic at the University of Sydney Law School, says Maya Cares is a perfect example of emerging technology that is contributing to a much broader shift within the legal profession – one that is challenging the role of the lawyer “as the sole and exclusive provider of legal services”.

The impact of new technologies in shaping and transforming welfare law, policy and practice is a key focus area of Wilcock’s, who also works as an associate investigator at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society, where she analyses the effects of automated decision making within the social services sector.

While technology changing the nature of legal practice is not “wholly unprecedented”, Wilcock says, the disruption to the legal services market by new players, including private companies and social enterprises, is a new shift. “We’ve got to share some of the work we do with new experts: they’re part of the business of law now,” she explains.

When apps and other technology-based solutions are primarily designed to increase access to justice, particularly for underserved communities, Wilcock says the potential to create positive change for the legal sector is “enormous”. However, on the other side of the coin, the corporate objectives of for-profit organisations entering this space increases the likelihood of unethical and negligent legal services being delivered to vulnerable individuals.

“Legal services and legal assistance chatbots are not created equal; they really can be quite different, and we need to look at them in context,” Wilcock says, citing the US jurisdiction, which has already been privy to a host of artificial intelligence-powered corporate legal solutions seeking to compete with and ultimately replace lawyers. “Depending on who owns or controls [the technology] and their purposes and objectives, the impacts and the potential for negative consequences can be really different.”

The solution, Wilcock argues, is to ensure that technology is used in ways that “supplement, facilitate and complement existing legal services”, particularly for the under-resourced community legal and legal aid sector.

The solution is to ensure that technology is used in ways that ‘supplement, facilitate and complement existing legal services’, particularly for the under-resourced community legal and legal aid sector.

Wilcock says apps and chatbots have a role in improving access and efficiency, and in “reaching people that aren’t getting their legal needs met”, but warns it is critical to be aware of the limitations of technology. “If they are providing legal services, they of course need to pay attention to quality and to effectiveness and to ensuring that practice management is as good as private legal services delivered elsewhere,” she advises.

A question of ethics

Ethical design is equally front of mind for Ashraf, who agrees that the law could become hostage to bias and misinformation if technology, particularly artificial intelligence, is left unchecked. To circumvent this damage, she says, apps and chatbots must be fed data that is prepared and informed by those with lived experience and who come from intersectional backgrounds so as best to represent modern society.

“If those writing the software don’t represent a balanced view of society, instead of the law protecting us, it could really end up being the opposite,” Ashraf suggests. “The flawed data of one individual or a handful of individuals could then impact millions of racialised people at scale, because that is how technology operates.”

The language used by Maya Cares was carefully crafted in consultation with FNBWoC with lived expertise – whereby an individual’s lived experience of racism and trauma intersects with their technical qualifications – before being beta tested by community members. While the chatbot currently relies on pre-written questions and answers, as more people interact with the platform, a larger database of information will be created, which will ultimately be used to support the transition to artificial intelligence.

The chatbot is powered by Josef Legal, a no-code software platform aiming to make legal services more accessible by automating legal tasks. By more efficiently capturing client information, lawyers’ time spent on initial discovery, and the associated costs and back-end administration, can be significantly reduced. Ashraf believes this innovation could contribute to the justice process becoming less “emotionally laborious for victims of crime”, who are often re-traumatised each time they are required to disclose details of their experience.

The bigger picture

Despite the intentions of a platform like Maya Cares, Ashraf believes the justice system as it stands today will continue to hinder the willingness of individuals, especially women of colour, to report racism. The legal system requires reform to better reflect Australia’s diversity.

“Nobody wants to have to go to court,” Ashraf says. “Because when you go to court, your future is in the hands of someone who may not understand your lived experience, especially where we don’t have the appropriate representation of people who are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, Black and Women of Colour.”

“Ultimately, the laws are still not appropriate. While I used my legal knowledge and experience to ensure that through Maya Cares, people will know what kind of rights they have, at the same time that can only take you so far because the laws themselves are not effective today.”

While Maya Cares cannot provide the entire solution, Ashraf feels confident in its ability to push forward public conversations about racism and provide much-needed timely support to individuals. The platform is already exploring new features too, from a translation tool to enable the chatbot to respond in different languages, to adding more accessible imagery and videos, and creating further personalised responses that better acknowledge the situation where the racism has taken place.

“We really hope that the legal community will lean in to assist us,” Priyanka concludes. “Because I think that’s where a lot of the power really sits.”