“It seemed like an attack on the law … because there was every chance a lawyer would be in there”

This week marks 10 years since the Lindt Café siege. It is understandably an anniversary few in the legal, police or intelligence communities wish to commemorate. Yet it remains a seminal moment worthy of reflection and analysis.

Mistakes were made, reputations diminished, and friendships fractured during, and in the aftermath of, the 17-hour siege in the heart of Sydney’s legal district on 15 and 16 December 2014 when gunman Man Haron Monis held 18 people hostage at gunpoint.

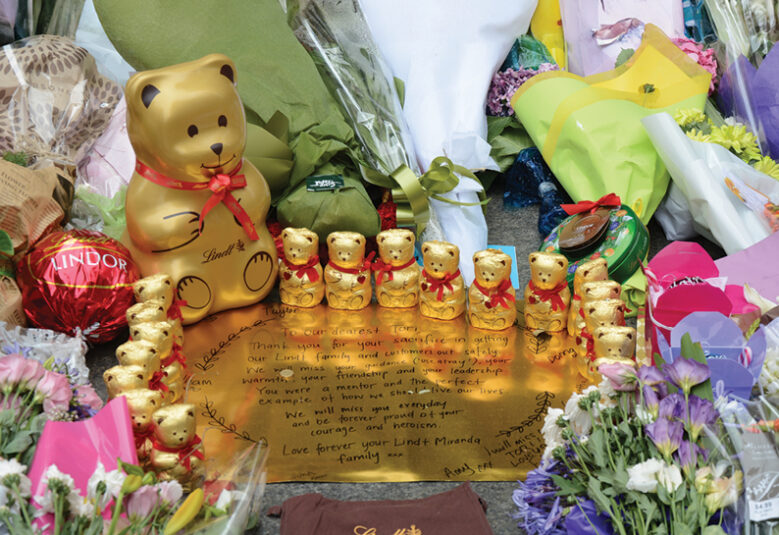

More importantly, two promising, young people loved by many in the law – barrister Katrina Dawson, and café manager Tori Johnson – died in the final moments of the traumatic event when the NSW Police Force’s Tactical Operations Unit officers finally stormed the café.

While the images of hostages wanly pressing their hands against the strengthened windows of the former bank branch in Martin Place are seared into Sydney’s memory, for the legal fraternity, the memories are so much sharper.

The Lindt Café on Phillip Street was a local. Phillip Street remains home to the Law Society of NSW, the NSW Bar Association, the Selborne, Wentworth and St James Hall chambers, and is only a Long Matters List away from the Law Courts Building on Queens Square.

The then-President of the Law Society, Ros Everett, recalls people working in the precinct “were all a bit jittery at the time” due to the heightened risk of an imminent terrorist attack on an iconic Sydney landmark. When news alerts started coming through of a terrorist attack at the Lindt Café, “It was just so personal to us because it seemed like an attack on the law.”

“We went into lockdown, trying to assess where everyone was because there was every chance a lawyer would be in there,” Everett says.

Understandably, many in the law do not wish to revisit the event or its aftermath. And a number of hostages have maintained their silence for nine years, including the two barristers accompanying Dawson at the cafe. Even NSW Police did not wish to provide any comment for this feature despite their subsequent improvements to procedures and resourcing.

“Anyone who had anything to do with it wants to bury it institutionally and personally, in many cases,” notes Deborah Snow, a journalist whose account of the event, Siege, was published in 2018. The need for change after the event was quickly obvious. But 10 years on, the desire to remember is weak, even though there are important reflections to consider. What have we learned from the event as a society but more particularly in the law, intelligence, police and media sectors? How has the justice system changed and has the legal profession recovered? If in the unfortunate circumstance of something similar happening again, how would we react? Operationally, many things would be improved but broadly, the answers are not as simple, or as reassuring, as one would hope.

Recollections of tragedy

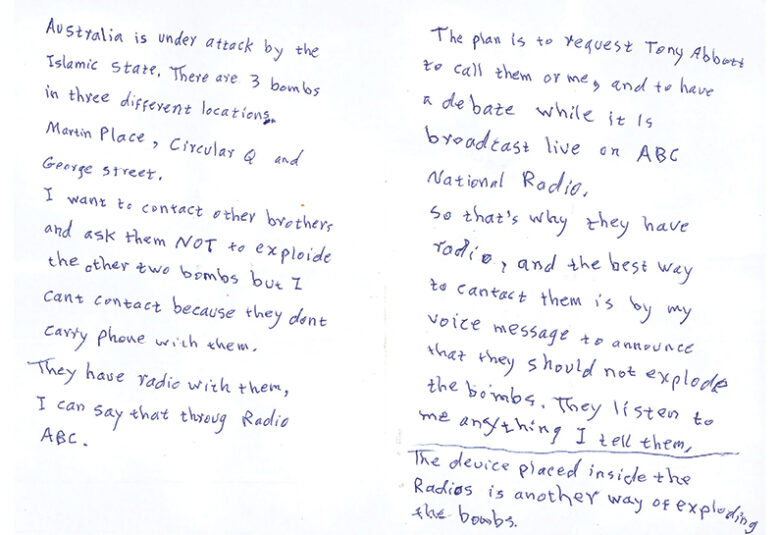

Within hours of Iranian political refugee and alleged sexual offender and accessory to murder accused Monis entering the Lindt Café, it became apparent this was an unfeasibly complex event. The nature of 18 people being held hostage in a small and well-fortified former bank branch was a logistical problem, exacerbated by the fact a television network (Seven) was broadcasting live from its newsroom only 20 metres away across Martin Place. Monis’s public display of a Jihadist flag confused matters, seemingly confirming fears this was a terrorist attack by Islamic State (IS). Yet when his name circulated among media, many relaxed somewhat because this serial pest’s vexatious grandstanding was infamous in Sydney.

“He had pulled many stunts before in public, he loved the media attention. So we genuinely thought he would walk out of there,” recalls Chris Reason, a senior reporter for Seven who covered the event.

But Monis did not walk out. Events descended so quickly that another journalist, Snow, would see the gravity. She has covered the security, intelligence and police rounds for decades and was intrigued how it was being managed as she watched it unfold from home.

“I was horrified at the way it ended, watching the flash bangs and thinking: Geez, this doesn’t look very clinical or controlled,” she recalls. “I knew enough to know this didn’t look like a very well-executed entry.”

That was confirmed in the days following as she spoke to security and intelligence contacts who all said the same thing: It was bungled.

And the event – and the bungling – would be of greater importance because “it involved high profile members of the legal community in their supposedly safe space, right on the doorstep of the courts and a TV station.”

The live, up-close coverage of the siege and the tragedy of the two innocent deaths, and Monis’s, meant the aftermath would include great legal, political and media scrutiny and heightened states of grief, adulation, and blame.

The federal government, led by Tony Abbott, and Mike Baird’s NSW government issued terms of reference for a joint review within three days of the attack. It was delivered within two months with 16 broad recommendations on immigration, firearms, and identity, among others. The speed of its delivery and reticence to step on the toes of the pending investigation by the NSW State Coroner possibly lessened its effect. The benign finding that during the incident “the judgments made by government agencies were reasonable and that the information that should have been available to decision-makers was available” was reassuring rather than instructive.

Ros Everett

Ros Everett

The NSW State Coroner’s ‘Inquest into the deaths arising from the Lindt Café siege’ would be an altogether different process. State Coroner Michael Barnes’ opening remark on 29 January 2015 that “it may be necessary to balance competing interests” would prove prophetic.

“It was an extremely difficult case,” says Barnes, now the NSW Crime Commissioner. “There were so many parties coming from so many different perspectives, and there were so many possible outcomes.”

Investigating deaths in police operations is fraught because police are inevitably doing their duty, which in this instance involved putting themselves in danger knowing Monis threatened to be carrying a bomb.

“But at the same time, two citizens end up dead while the police are there, so you have to ask the question could they have done it better?” Barnes says.

The long search for answers

The inquest’s first hearing began on 25 May 2015 and the fourth segment concluded 17 August 2016. Coroner Barnes delivered his 472-page report and 45 recommendations seven months later, on 24 May 2017, under some duress to conclude before the awful prospect of another terrorist attack. Two weeks later, the NSW Government accepted and supported all 45 recommendations and a fortnight later, the Government presented the Terrorism Legislation Amendment (Police Powers and Parole) Bill 2017 to NSW Parliament.

Of major consequence was Barnes’ affirmation Monis was a terrorist. This fact clarified some aspects of the legal and political response to his actions, yet some prefer to still believe he was merely a mad man and not a terrorist.

At the time of the incident, Monis was on bail, with 40 charges of indecent or sexual assault of seven victims pending, alleged to have been committed whilst he professed to be a “spiritual healer.” He was also charged with being an accessory to the murder of his former partner and his professed status as a Shi’a Muslim cleric was bogus.

Middle East terrorism expert Rodger Shanahan, who spoke at the inquest, accepts Barnes’ judgement but argues it was not an act of terrorism because Monis’s mental health issues overrode that.

“I didn’t think he did it for political or religious reasons. He did it for himself; he was a violent narcissist who was facing a raft of very serious charges,” Shanahan notes. “He was fixated on a whole range of things, and he was just a nasty horrible person.”

Barnes remains adamant “having obsessive behaviour doesn’t mean you’re not a terrorist.”

“There used to be a false dichotomy that you were either mad or bad,” Barnes says. “Most people would think ISIS fighters who slice people’s heads off in the desert for their religious or political cause, are crazy but that doesn’t mean they are not terrorists.”

Indeed, submissions were made for the inquest to go to Iran to investigate Monis’s background, a request deemed unfeasible.

What makes a fixated person?

The diverse and dangerous nature of Monis’s behaviour elevated scrutiny of a number of criminal and judicial issues, some of which have been addressed (incident assessment and surveillance), while others remain vexed (sexual assault as violence) or political footballs (bail).

Barnes considers a key issue emerging from the inquest remains the appropriate risk management of people like Monis, who clearly was a threat. “How do we deal with these people who are borderline?” Barnes asks.

Monis’s prior behaviour was public and radical, yet security agencies had made adequate assessments of him. Still, the idea agencies such as ASIO should have such people on constant watch persists. Yet even when they do, public safety can’t be guaranteed, as was shown in 2021, when a “violent extremist” under heavy surveillance by New Zealand police, stabbed six people in a West Auckland supermarket. He was shot dead at the scene by the police who were only 20 metres away monitoring him.

In April 2017, former Police Commissioner Mick Fuller established a Fixated Persons Investigations Unit (FPIU), pre-empting the inquest’s findings and recommendations. Following UK and Queensland models, the unit aims to monitor extremists and fixated persons who may not fall under Australia’s counter-terrorism laws but nonetheless pose a risk of serious violence. The definition of a fixated person as someone with “an obsessive preoccupation, pursued to an excessive or irrational degree” is broad. So, eyebrows were raised when the FPIU arrested Kristo Langker, the 21-year-old producer of YouTube enfant terrible Friendlyjordies’ (Jordan Shanks) in 2021 for allegedly stalking and intimidating NSW Deputy Premier John Barilaro. All charges against him were later dropped.

Shanahan argues police generally do an effective job monitoring threats and using their experience when dealing with people for extended periods of time.

“The siege didn’t really change the way police looked at individuals but legislatively and organisationally it was how to deal with somebody like Monis,” he says.

“It was a strange thing looking back on it because he was unique because he was so hard to define. Looking back, would the police have paid more attention to him (with a FPIU)? I don’t know if they would have.”

Societal mores have tightened in one definition of behaviour though. Despite Monis’s 40 charges of indecent or sexual assault of seven victims pending, the police response on the day to his hostage-taking was driven by a view that he was not violent, or likely to be.

Hostage Louisa Hope is still incredulous at this “gendered worldview” that influenced patience rather than action at the Lindt Café.

She recalls the inquest testimony “went through me like a knife because I realised the whole way the police managed the siege was on the assumption he was not going to be violent. What man makes a decision that a man that sexually assaults someone is not violent?”

Certainly, the unnamed consultant psychiatrist advising police didn’t, even ask whether Monis “had the ticker” to kill. “Imagine if 10 years ago they’d thought, he’s up on sexual assault charges, we should take this seriously,” Hope asks. “Imagine what a difference it would have made to the siege.”

The fact Monis took hostages while he was on bail awaiting trial became a public cause celebre but it was not a focus of the inquest. Barnes recalls stirring up concern among the legal profession with his decision to examine the Director of Public Prosecution’s handling of Monis’s bail application while he was awaiting trial on serious sex offences. He understood the argument it wasn’t within scope but believed “it was such a key element (the fact) they had not opposed the bail application.”

Rodger Shanahan

Rodger Shanahan

“I didn’t think he did it for political or religious reasons. He did it for himself; he was a violent narcissist who knew the jig was up and he was going to go down for all the charges”

“I thought it was an issue that the families of the victims deserved some answers on and how and where were they going to get them if it wasn’t done in the inquest?”

Everett, the President of the Law Society at the time of the siege, recalls a major review of NSW bail laws had only recently concluded in 2014 and after the siege “it was all thrown up again. It happens all the time, every couple of years,” she says.

Her then-colleague at the NSW Bar Association, Jane Needham SC, agrees and notes a more personal consequence.

“Most of the time the bail system works well, so it’s unfortunate this blew up in the days afterwards because our members were getting death threats and judges were being personally attacked,” she recalls.

For the law, issues in a subsequent review of bail beyond merely the mechanics, became how to protect judges and lawyers and how to defend the legitimacy of bail laws in the media and public sphere.

A trigger for change

The NSW Terrorism Legislation Amendment Bill 2017 addressing police powers and parole was the most substantial legislative reaction to the siege. Essentially the Bill clarified responsibility for when and how police could use lethal force. It also removed them from criminal responsibility by allowing the Commissioner of Police to authorise the use of force reasonably necessary to defend anyone threatened by a terrorist incident or to secure the release of hostages.

In practice, this clarification of responsibility has aligned with a quantum change in the way NSW police respond with force. In 2014, any officer who pulled the trigger of a gun had to have justification that if they didn’t, they or another person were likely to die or come to serious harm. That placed enormous pressure on the high-stress decision-making process police encounter.

Certainly, police had a narrow, even cautious, view of their power and believed they could not kill unless there was an immediate threat.

Depending on who you ask, that tempered the police response to disable Monis. Incredibly, and to the later dismay of the hostages, during the siege, the NSW Police Force (NSWPF) raised the threshold for entering the cafe to be the killing or serious harm of a hostage.

The new law has eased the responsibility on individual officers by saying senior management can declare the power to use deadly force, transferring responsibility to where it should sit, at a higher level. Supposedly the change was welcomed by the rank and file, who had questioned the operational capability of some of their high-profile seniors. And the result became apparent 10 years later, in April 2024, when the murderer of six people at the Westfield Bondi Junction was shot dead by the first police officer to approach him. Today, an active shooter is neutralised as safely as possible, as soon as possible.

This is a major pendulum swing from the previous “contain and negotiate” police strategy for such situations. That itself was a consequence of decades of opprobrium directed at police for being too trigger happy and charging into incidents with stun grenades and hot guns. The current medium considers how police need to keep the community safe while keeping themselves safe too, by keeping as far away from the threat as they can.

It was easy for newly-appointed Police Commissioner Mick Fuller to acknowledge that police took too long to breach the café. His predecessor and Commissioner during the siege, Andrew Scipione, retired in April 2017, one month before the inquest’s publication.

The inquest was scathing of the police decision-making process and of the lack of skills and resourcing required for the negotiation. The negotiation was unnecessarily obdurate, not providing Monis anything to calm or appease him, which ratcheted up his fervour. The lack of proper resourcing also meant police didn’t know this. They were unable to monitor accurately by a listening device or visual surveillance what was going on in the café. “He was getting more and more agitated but they weren’t picking this up properly,” Snow says.

Furthermore, the inquest heard the chief police negotiator was engaged in up to four other incidents around NSW simultaneously as they attempted to resolve the siege inside the Lindt Café.

Sources suggest the many operational recommendations for police operations, including an overall review and reengineer of the Negotiation Unit, were promptly instituted, often with ease and relief.

The NSW Police refused to comment to the Journal and its unwillingness to reveal operational matters is clear. Nevertheless, it is known the Negotiations Unit within its State Protection Group has new leadership, staff and practices, including a new ‘Negotiation Bus’, even if they won’t confirm it.

Seven Network senior reporter Chris Reason agrees the secrecy remains a bugbear for the media. “The cover and cloak of terrorism has always been a deeply held secret but at some point they should reassure the community and say yes, they have learned,” he says.

One officer unauthorised to speak says the changes were brutal. “They sacked everyone involved in all levels of negotiation and started again. They got lots of new equipment, got a competent female officer to run it, and I’d suggest the negotiators are far better than they were, and they have a terrorism team on full rotation.”

Louisa Hope and other hostages gave feedback to the police, and she’s subsequently observed changes with police operations. “There’s a lot of very good work the police, including the negotiating team, have done and that is to be commended,” she says.

The frontline response

The cross-jurisdictional co-operation during the siege also proved clumsy. Commonwealth agencies took the view management of the operation was well within the capacity of the NSWPF, which was a logical assumption given the field of action was so contained. Nor did the NSWPF feel the need to call on the ADF.

Yet without the surveillance capability to get eyes or ears in the café, more sophisticated help could have changed the operation. Snow believes the later revelation that the NSWPF refused to accept an offer of help from ASIO, of a sort that we don’t know, was “really important because it goes to the longstanding rivalry in this country between federal and state agencies.”

As it happened, the Coroner recommended the ADF confer with state and territory governments about applications for the ADF to be called out under the Defence Act 1903 (Cth), which the NSW Government supported.

An odd tangent emerging from this assessment of the cross-jurisdiction malarkey would be of great consequence elsewhere. Given the public discussion about whether army special forces should have been brought in to deal with the terrorist act, Australian Special Operations Commander Major-General Jeff Sengelman commissioned an assessment of whether his soldiers had the skills to do a better job and whether, indeed, the army would be welcomed.

He engaged sociologist Samantha Crompvoets to discuss with a range of agencies, including ASIS and police forces, what the potential of any future role in domestic counter-terrorism might be. Her interviews uncovered damning reflections of the special forces, which she included in an appendix to her report on agency views of military involvement in “civil events such as sieges”.

Stories emerged of illegal atrocities committed by the Special Operations Task Group in Afghanistan, which were escalated to Army Commander Lieutenant General Angus Campbell before Justice Paul Brereton was commissioned to investigate war crimes allegedly committed by soldiers in Afghanistan.

The Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force Afghanistan Inquiry Report released in 2020 found evidence of 39 murders of civilians and prisoners by (or at the instruction of) members of the Australian special forces. The dramatic ramifications, including ADF reforms, disgrace for Special Operations Command, and possible prosecution of war crimes, are ongoing and often secretive.

Transparency and suppression remain festering issues in the wake of the Lindt Café Inquest. The necessity of closed court hearings and publication restrictions will never satisfy those who desire utter transparency, particularly as state and federal agencies sometimes use confidentiality as a convenient cloak.

Opinions are divided on whether the two senior police officers in charge of the Forward Command Post – possibly the two most important people outside the café – should have been named.

Certainly, the man who ultimately shot Monis during the extraction, ‘Officer A’, is now fighting to have his name made public. His lawyers made the initial suppression order in case of reprisal, and another was made by the NSWPF.

“Since that time, there’s no real worries for me regarding ramifications and I want to put my name to my story,” he says. Not for self-aggrandisement but to help others dealing with the same issues he encounters.

Yet despite an application to lift the suppression, he’s been advised the State Coroner can’t do so without another inquest.

“Does that mean a suppression order in any coroner’s matter is enforced forever?” he asks. “It doesn’t make sense, does it?”

Officer A told the story of the NSW Tactical Operations Unit in his book Tiger! Tiger! Tiger!, published in 2022 and, to his credit, he’s done the right thing and maintained his anonymity. But he’d like his agency back.

Reporting close to home

On the day, the media vacillated for some time on whether to identify Man Haron Monis as the suspect when they knew, quite early on, that it was him. Police warned them off doing so, not knowing how disclosure might affect him.

Chris Reason recalled US TV show Fox and Friends asking during a live cross whether they knew the hostage taker’s identity. Reason replied yes, but that journalists had agreed not to reveal the name at the request of police.

“And the American hosts went into meltdown! ‘Are you telling me you’re being controlled by the police?’” he laughs. “They turned it into a press freedom in Australia story, but Australian reporters were able to work in a responsible way.”

“There were boundaries set for us on the day; when I walked in, they said you can’t show this site live, or the gunman live, and we agreed to all of those.”

It doesn’t always work though. The Seven Network this year settled with a man it erroneously identified as the murderer of the six people stabbed at Bondi Junction.

“Journalists will take any licence they’re given, so it’s really up to those who are managing these situations to strike the balance between the public’s right to know and the safety of hostages while not endangering those hostages or others in the front line like officers, or ambos,” Snow says. “It’s not up to journalists to self-police.”

Reason says the relationship between police and media during the siege was as good as it could have been although 120 staff had to evacuate the Seven newsroom and studio opposite the Lindt Café, so Seven had to broadcast nationally from its Melbourne studio.

“One of the biggest stories of my career ended up happening 30 metres from my desk,” Reason notes.

“We went away and had some serious learnings about what we could do better, but the nature of news is no two events are identical.”

Seven has since left Martin Place but it has also created a redundancy studio so it can continue to broadcast from Sydney if an event were to disable its Eveleigh studios.

Louise Hope

Louise Hope

“What man makes a decision that a man that sexually assaults someone is not violent?”

The fallout

Ultimately, changes to laws, police practice or media and security matters seem trivial to those dealing with the personal fallout of such an event.

Officer A, who shot Monis, says his is a “typical PTSD story: went off on workers comp, got divorced and all that jazz.” Many police officers have left the force subsequently and so many reputations were damaged.

The hostages have dealt with their experience separately. Some have not and will not speak. Certainly, there appears to be no enduring bond between the hostages collectively or the families of the two victims, with some animosity lingering about individual behaviour during the siege and afterwards.

Louisa Hope, who has become a spokesperson and victim’s advocate preaching forgiveness has raised money for charities and is in the early stages of establishing a support group for the victims of terror in Australia and New Zealand. “There’s a whole lot more than people realise,” she says.

“For me personally, after the siege, I knew we had to get something good out of it because quite frankly I thought there’d be race riots on the street the next day. So, for me, post-siege, I went up instead of down,” she adds. “I think I had post-trauma euphoria, just so grateful to be alive, but there’s been subsequent trauma I’ve had to deal with.”

In the shadow of tragedy

The impact on the legal profession has been mixed. Initially, amidst the shock, the sector quickly bonded. Needham recalls in the days following the siege the Bar Association found “people were really looking out for connection, and it seemed to really affect women a lot”, so they offered a number of events where people could assemble and attempt to cleanse, grieve or decompress.

Everett agrees “the aftermath was a great coming together for all of us”, including candlelight vigils and a heart-breaking service held at St James’ Church.

“What was remarkable was the sense of community and how tight the Phillip St and legal community is,” recalls Michael Tidball, then CEO of the Law Society.

But it was difficult to leave behind; one lawyer describes how “confronting” it was passing and smelling the mass of flowers in Martin Place every morning on their way to court. And Dawson’s chambers overlooked this public display of grief.

Our BarCare program had a line asking, ‘why did you come?’, and the ‘siege’ response was a focus of quite a lot of our wellbeing and care afterwards,” says Needham.

“It was just such a powerful time for all of us and I can’t believe it’s been 10 years since then,” adds Everett.

In an inquest in which blame would be apportioned, reputations would be defended and many pained people would want an outlet or justice, conflict among interested parties and the counsel representing them was perhaps to be expected.

“By the time it got to the inquest, everyone had their own lawyers,” said one source unwilling to speak publicly. “And the police knew they had to limit the damage. You had the Commonwealth saying there’s nothing to see here and the state government and police saying we did everything right.”

Hope concedes she was ignorant of the law “so to be there was really astounding to watch.”

“I believed we were there to discover how things could be done better next time collectively (but) I went in and discovered not everyone was playing on the same field. That was a shock,” she says.

The inquest was very long and very difficult for everyone involved and, at times, counsel could be disingenuous, aggressive, or spiteful defending their clients. Also, some parties attempted to avoid giving evidence on their actions, which elevated animosity and even led to some conspiratorial beliefs. The proceedings clearly fractured some relationships and eroded some mutual respect. It’s instructive no counsel approached by the Journal wished to talk about the proceedings.

“By the time it got to the inquest, everyone had their own lawyers. And the police knew they had to limit the damage. You had the Commonwealth saying there’s nothing

to see here and the state government and police saying we did everything right”

As one party says, “It was very difficult but it also says the pursuit of the truth and interrogating facts and the process of making findings speaks to the heart of the rule of law and what it does and it’s to society’s benefit that that overrides the relationships within the profession.”

Many are still haunted by the siege. This December anniversary, and the commensurate media attention and re-analysis, will be bracing. As one lawyer notes, “I still think people are unhappy about it.”

More broadly, despite widespread praise for Barnes’ inquest, findings and recommendations, and, more quietly, for the police and government response and improvements, there appears to be a general unwillingness to remember or discuss the Lindt Café siege. And any acknowledgement of it is reticent.

Seven cameraman Greg Parker, who set up a camera inside the Seven studio and updated police, received a Police Commissioner’s Award in February this year, nine years after the event. Similarly, 28 members of the NSWPF’s Tactical Operations Unit, Negotiation Unit, Rescue and Bomb Disposal, Dog Unit and Highway Patrol, and four ambos, will receive Group Bravery Citations from the Governor General later this year for their work during the siege. Officer A, if his name remains suppressed, will not be able to attend.

Even the memorial in Martin Place, with 200 hand-crafted flowers inlaid into the pavement – is subtle, and one block from the former café. People still walk over it today.

“For me it speaks to something, they’ve tried to not hide it but put it a block away,” says Reason. He adds the cafe site remains a constant reminder for everybody in the legal community. “It’s stacked with implication and mourning and the heaviness of that day. It’s a standing memorial in that sense.”

The memorials to the legal life lost remain the most tangible and ongoing. “The law lost such a legal mind,” with Katrina Dawson’s death, says Everett. “In such a short time she touched so many lives in such a positive way.”

A spokesperson for 8th Floor Selborne Chambers said in a statement “the Lindt Café siege and the loss of Katrina Dawson were shocking and devastating events, the effects of which are still being felt today. In particular, the loss of Katrina Dawson was an immeasurable loss to her family, to the legal profession, and to her friends and colleagues.”