Since the Taliban took over in Afghanistan, Afghan women judges have lost their sense of security. Three of those women, who have sought asylum in Australia, share their stories here.

On 15 August 2021, almost 20 years after the US and Allied forces invaded Afghanistan in October 2001 to forcibly remove the Taliban, the Sunni Islamic fundamentalist regime returned to power.

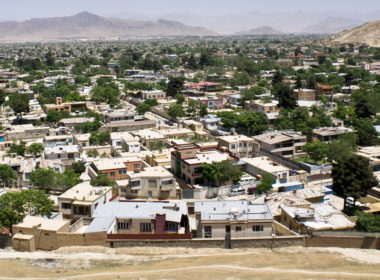

A mere fortnight before the official US withdrawal deadline, the Taliban overtook Kabul, announcing later that day that they had established control over the capital. President Ashraf Ghani fled the country, the government collapsed, and in the following weeks suicide bombings and Taliban attacks on citizens seeking to flee the troubled country resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Afghan men, women and children.

Women judges were among those who were particularly terrified for their lives. After the foreign troops withdrew, the Taliban released thousands of prisoners, including Taliban leaders, murderers and drug traffickers whom the judges had sent to jail. This left these women vulnerable to reprisal.

A home in Australia?

For governments worldwide, accommodating an influx of asylum seekers, many with fear for their lives, was a sensitive issue – and a logistical crisis. As of August 2022, authorities in Canberra have received more than 200,000 applications from Afghan asylum seekers, but almost half are still awaiting consideration.

Andrew Giles, Australia’s Immigration Minister, ordered a review into Australia’s handling of the asylum crisis, acknowledging that the processing system has been overwhelmed. On 15 August 2022, a year after the Taliban takeover, Giles announced: “Australia will offer 31,500 places to Afghan nationals under the Humanitarian Program and the Family stream of the Migration Program over four years, and Afghan citizens will continue to be prioritised for processing within Australia’s Humanitarian Program”.

The world’s largest humanitarian crisis

Following its legal reconstruction in 2001, informed by US, Japanese, European and UN input into training judges, reinstituting tribunals and recodifying law, Afghanistan experienced the greatest increase in the number of female judges in its history.

By 2020, the country had between 250 and 300 female judges (comprising 8 to 10 per cent of the judiciary), mostly working in Kabul.

By 2021 those judges were fleeing their homes in fear of their lives.

Today all Afghans are living in the midst of the world’s largest humanitarian crisis, according to the United Nations. In August this year the UNHCR declared that six million Afghans were on the brink of famine.

Hundreds of thousands of citizens have fled Afghanistan and have been granted refugee status in countries across the world.

According to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia evacuated approximately 4,100 people from Kabul between 18 and 26 August 2021, including hundreds of Australian Defence Force members and government officials.

Not expecting to return alive

Judge Nellab Hotaki Talash left Afghanistan on 22 Oct 2021 for Athens, Greece, and arrived in Australia on 24 Jan 2022.

Judge Talash was a judge in Kabul for more than ten years. She says, “I have worked in different courts: the supreme court, internal and external security courts, administrative corruption court, and, finally, the court of investigation of [criminal] violence against women in Kabul city.”

Prior to the Taliban takeover, Judge Talash received threats. “There were letters, phone calls, warning messages and some other type of threats, but in the final two years it got very serious,” she reveals.

Judge Talash would like to pursue work in Australia as a judge, but she concedes that she has a limited understanding of the judicial system here, and she is still working on her fluency in English.

Of her colleagues at home, with whom she remains in regular contact, she says, “They are all hopeful, as the International Association of Women Judges is linked with them and attempting to get them visas for evacuation.”

Via an interpreter, Judge Shakila Abawi Shigarf recalls her 26 years working on criminal and civil cases as a judge in Kabul.

“I worked with different courts and court departments, including the family court, the children’s court, and the court’s branch for crimes against national and foreign interest and security of the country,” Judge Shigarf says.

Her life had already felt endangered prior to the Taliban taking over Kabul, but once they released the prisoners the threat to her and her family was exacerbated, she explains.

“Two of our female judges were targeted and killed by Taliban in 2021 when they were going to their offices. We were terrified and worried as the Taliban had identified us and we were not able to go to the courts easily. Their warnings and threatening messages were officially notified to us by the legal and judicial authorities and the security units. We were leaving our homes in the mornings for our offices, but we were not [expecting] to return alive.”

‘We were leaving our homes in the mornings for our offices, but we were not expecting to return alive.’

When the Taliban took over the country on 15 August 2021, Judge Shigarf says, “They immediately terminated all the judges, froze our bank accounts and started a house-by-house chase and search. It made it very difficult for us to stay in Afghanistan.”

She and her family received Australian humanitarian visas with the support of the International Association of Judges and the Australian Association of Women Judges, and eventually arrived in Australia via Frankfurt, Germany.

The Australian government has provided support with housing, Centrelink payments, and free English language courses. Judge Shigarf is aware that this is not a freedom experienced by many women in Afghanistan, including many women Judges.

“The Taliban are a manufactured terroristic group who do not have legal knowledge and understanding. They are currently prosecuting and sentencing people in public areas based on their own perceptions and personal understanding, and not based on any legitimate laws or the Sharia, and their practices have been against the human rights of Afghan people,” she says.

“The Taliban after taking over the control of the country didn’t only destroy the judicial branch but also the executive and the legislative branches, and the national army, national police and the intelligence, which were all established on the basis of a democratic regime.

“I believe that if an inclusive government is formed that includes different tribes and ethnic groups, and is based on democratic elections, [with] women are a significant part, the rebuilding of the judicial system will certainly become a reality again.”

An unclear destiny

Judge Sayeda Wasiq outlines her work history via interpreter: “I worked as a judge for six years with different courts and court departments of Herat Province in Afghanistan, including the Children’s Court, and the Public Security and Criminal Justice Departments of the Appellate Court of the same province.”

She left Afghanistan with her family on 24 Oct 2021 and arrived in Darwin on 17 November 2021. Two weeks later, they moved to Melbourne.

“According to my experience of a court trial in Melbourne, which I was invited to, and the discussions I had with Australian judges about the laws of Australia and Afghanistan, I can generally say that there are similarities between the Australian and Afghanistan laws. However, there are some differences as well,” Judge Wasiq observes.

“I am very interested in working in the Australian judicial system in the future.”

She is less optimistic about the current state of the judicial system in her homeland.

“It is in the worst situation now, and the judges are suffering an unclear and ambiguous destiny. Judges are collectively terminated [from their positions as Judges in Afghanistan], and they must [engage in] hard labour and casual work to feed their families. Yet they cannot come out of their homes and breathe freely as they are suffering threats to their lives.”

Judge Wasiq adds, “I hope that all relevant Australian organisations who are working on humanitarian causes will provide more support and help to Afghan judges who are still in Afghanistan.”

Read more about the 2001 legal reconstruction in Afghanistan here.

The author would like to thank and acknowledge the support of Frances Atkinson and Robin Astley of Victoria University for arranging the interviews for this story, and Ahmad Shiwa for his expertise in translating Dari into English.