“People are being incarcerated many times and things aren’t changing. One of my goals is to get these reports embedded in legislation, because currently this is optional. We want to do more work with politicians to highlight the importance of diversionary measures”

How do participants in the criminal justice system view the people who hold power? When leadership wavers, individuals are forced to take charge of their own story. In the first part of this series, we explored the victim experience, and now, we investigate the seemingly opposite side - the experience of offenders.

INSIGHT INTO OFFENDING

Every fortnight, Keenan Mundine attends counselling. But he admits that the exercise feels like an anomaly. He tells the Law Society Journal that, had his younger self had access to the care and guidance he now has as a 36-year-old, it could have changed his trajectory.

The proud Aboriginal man is still coming to terms with his childhood trauma: a little boy who grew up in Redfern, notoriously known as “The Block”, orphaned and homeless. He is working to understand how the choices he made as a juvenile – that propelled him into a vicious cycle of crime, drugs, and incarceration – were heavily influenced by his circumstances.

Mundine lost his mother to an overdose when he was six. His dad passed away – by suicide – a year later. He was subsequently placed into care and separated from his two older brothers.

“As a young boy who experienced early-childhood challenges, I never asked to be born into such a life … I was expected to grow into a pro-social young person without counselling or support,” he says.

On a bluebird winter day, Mundine sits down with the Journal in the backyard of Deadly Connections, the Aboriginal community-led not-for-profit he co-founded with his wife, Wiradjuri woman Carly Stanley. It’s an unassuming yellow brick building on the corner of Enmore Park in Sydney’s Inner West, but the work that goes on there is nothing short of lifechanging.

Deadly Connections, Australia’s only justice agency controlled by the Aboriginal community, was formed in response to the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in both the child protection and justice systems. Since the organisation’s humble beginnings in a space in their home in 2018, Mundine and Stanley have offered holistic, culturally safe programs that combine lived experience with professional support.

Through these services, children and young people are prevented from entering the criminal justice system by education, connection to culture and mentoring. For adults, it’s about diversion. Despite resourcing and funding shortfalls, Deadly Connections reunites families, engages primary-aged children in traditional dance programs, helps disengaged youths return to school, and drives down re-offending.

“You can see what we have built in there,” Mundine says, motioning to the office. “It is hard for me to sit still and enjoy it. No matter how far I remove myself from my experience, no matter how successful I am, I still see the world through the eyes of that little boy.”

A study by the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) from March 2022 reveals that Aboriginal children are 17 times more likely to be in both child protection and youth justice supervision than non-Aboriginal children. It’s no surprise that as a teenager Mundine saw the criminal justice system as an inevitability. He was first locked up at 14 for breaking into a car to steal a laptop, beginning his lengthy involvement with the CJS. Then he was incarcerated repeatedly for petty theft, varying from two-week to six-months stints. By 16, he was labelled a recidivist offender. His 18th birthday was spent in a boys’ home, a trend that continued until his late 20s.

“I had more of a life in prison. My two older siblings, all my uncles, and the majority of the boys that lived on my street in Redfern were in prison with me,” he says.

“Within the space of eight months, I went in front of the Judge no fewer than eight times. The way judicial officers delivered their language made me think I was a recidivist offender. They’re the experts, and they were telling me: ‘This is the label we’re going to give you because of a, b, and c’. I did those things so I must be a recidivist offender, was my attitude. I thought there was no other way to intervene at that point.”

The conversation takes an emotional turn when Mundine reveals his children – boys aged five and six – are now the age he was when he lost his parents.

“Nobody ever said, ‘Keenan, you’re 14 and you’re in pain and when you become a father you are going to have to push through it to talk to your children. Nobody I know got out of the criminal justice system. Even now, I pinch myself. Once you’re involved, the only thing is jail and death.”

‘An idle mind is a devil’s playground’

“One of the major failings of our legal system is that it’s not inclusive. We have to take greater ownership of the process,” victims advocate Brown says.

“We tend to typecast all the players. For example, if you’re in the dock, you’re automatically a scumbag. But a lot of people who are in the dock aren’t scumbags,” Brown adds.

While Brown is on the side of victims in the criminal justice system, he has a cyclical perspective of the process. Until December 2021, he was a foundation member of the NSW Sentencing Council, an independent body comprising judges, prosecutors, criminal defence lawyers and police who advise the Attorney General on sentencing matters and trends. Creating educational and vocational pathways to make prison sentences more fulfilling was a key focus in Brown’s time.

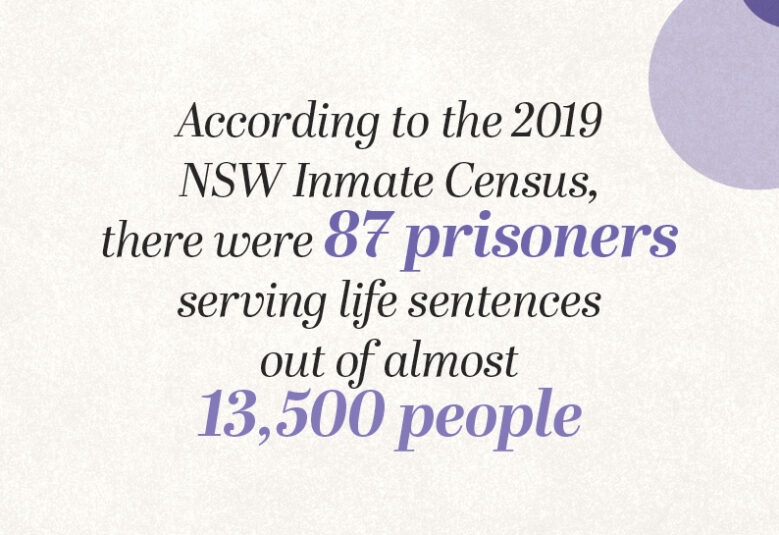

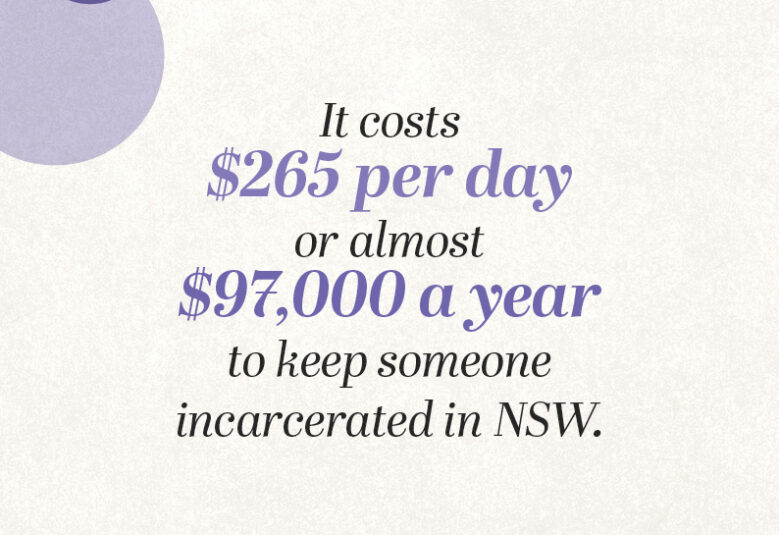

It costs $265 per day, or almost $97,000 a year, to keep someone incarcerated in NSW. According to the 2019 NSW Inmate Census, of almost 13,500 prisoners, 87 were serving life sentences. While the overall prison population has declined slightly since then, Brown tells the Journal the logic in these statistics is that everyone who isn’t serving life behind bars is going to be released.

“We are putting people in halfway houses with 15 other offenders. We can’t place barriers like this on people returning to a normal civilised life.” Brown says.

“It’s going to cost more money to put solutions in place, but it is always going to be cheaper than what it is costing us per prisoner for every year they are in custody.”

“In the Tania Burgess case, when you are talking about people like DL who have substantive sentences, you not only have to counteract their offending behaviour, but also accommodate their needs in relation to being institutionalised.”

Mundine was entrenched in the criminal justice system. Each time he was released, he returned to the same poor socio-economic circumstances, saddled by the stigma and unemployment challenges that come with a criminal record. With nearly one in three Aboriginal people living below the poverty line, for Mundine prison meant he never had to worry about a meal, a bed, paying rent or electricity, because these were provided for him. “The system does nothing to build independent young people,” he says. “I lost all trust in any of the orthodox approaches to working with someone like me, because they let me down. In jail, I got my forklift licence, a Certificate II in warehousing, a white card for construction, and I was a bonded asbestos removalist. But I couldn’t get a job when I was released. I assigned my pathways over to professionals and it didn’t get me to where I need to be.

“The other messed up thing about being entrenched is that I didn’t have to worry about committing offences in prison. It was a place where I could rest, live life, and not worry about having my door kicked in.”

Mundine saw an opportunity to take back control of his life and break out of his toxic prison cycle in 2013, after committing a robbery while on parole and “high on ice, pills and heroin”. As an alternative to a sentence of a decade behind bars, a rational and humane judge heard Mundine’s plea to attend an internal drug treatment program at Parklea Correctional Centre in Sydney, giving him access to intensive therapy and eventually day leave.

“The judge wanted to throw the book at me. He said, ‘This is the same parole you’ve violated twice. You haven’t done anything to rehabilitate’. I said, ‘Let’s stop talking about reintegration because that is for people who have a life to reintegrate back to. I came to jail at 18, unemployed, homeless, no bank account, no tax file number, no social welfare benefits, and never lived independently. While I was in prison I needed to build a life to come out to.’”

In his experience on the NSW Sentencing Council and from appearances in front of the State Parole Authority, Brown says most of the participants who end up back in the system are released without a connection to community. “There is an old saying in the Catholic Church, ‘an idle mind is the devil’s playground’. If we’re not giving prisoners skills to live in the community, we need to do more to secure employment for them. With unemployment at rock bottom, we’re in an ideal situation right now. We desperately need people to do mundane work. We have prisons full of people who can fill those positions.

“We see how many law-abiding people are struggling with cost-of-living pressures. We are asking prisoners to adopt that lifestyle and say, ‘by the way, you’re on your own’.”

The criminal justice process isn’t set up to treat anyone. It’s a punitive approach. You are accused of said crime, which equals said amount of time in custody; the process doesn’t care if you’re homeless and your father killed himself. People are told, ‘just make better choices and don’t break the law’

Understanding recidivism

Almost 24 per cent of adults found guilty in 2020 re-offended in the following 12 months. In September 2018, reforms gave judges and magistrates access to new, flexible community sentencing options – including curfews, home detention, electronic monitoring and community service. But an evaluation of the reforms by BOCSAR found this didn’t reduce re-offending, bringing home the points made by Brown and Mundine about reintegration.

Corrective Services NSW uses a compendium of 30 rehabilitation programs for offenders both in custody and in the community, designed to address specific offending behaviours and the risk factors for re-offending. The EQUIPS programs target the largest number of offenders across NSW at a medium to high risk of re-offending. It addresses aggression, domestic abuse, and addiction. High-risk male offenders serving more than two years in custody for a violent offence can access the 12-month Violent Offender Treatment Program (VOTP).

Barrister Greg Barns is a patron of the Justice Reform Initiative, an alliance that advocates for alternatives to incarceration and pathways out of the prison system. But he tells the Journal that many of the rehabilitation programs are tokenistic. “Prison is simply warehousing people with mental illness, people with acquired brain injuries, people who have had extraordinary disadvantage in their lives. Rehabilitation efforts in prison are subject to political whim and underfunded, and in any event the prison environment is not conducive to people being able to focus on rehabilitation.”

Brown says greater access to programs will ultimately give victims greater trust in the court process and prison system. “The VOTP is an excellent program, where you get one on one treatment with psychiatrists and psychologists. But the problem is they can only run it in units of about twenty,” he says. “In contrast, in Mandy and Chris Burgess’ case, when your daughter has been stabbed forty times by an offender, how are you supposed to know what a VOTP is? That is why I see my role as so important, because people are concerned about a person’s potential release to parole. They want to know if the person has done something to try to deal with their offending behaviour.”

Offenders are assessed for programs when they first enter the prison system, using a tool called the Level of Service Inventory – Revised (LSI-R). It considers criminal history, education, employment, family background, financial circumstances, and alcohol and drug problems. It then ranks an offender on a scale from low to high based on their likelihood of re-offending.

“If you identify as homeless or unemployed, that is a risk of re-offending … The madness on top of that is that just by identifying as Aboriginal your risk of re-offending is elevated,” Mundine explains.

Brown is also an advocate for day leave and work release programs that allow offenders to readjust slowly back into the community. Mundine praises this structure for helping change his trajectory and allowing him to confront his demons. “I was able to go back to Redfern with a bracelet and navigate my community. I practised not engaging in destructive behaviours and seeking out anti-social people … It triggered me, but I had to do it without participating,” Mundine says.

“The structure was not culturally safe. It didn’t connect me back to my history or my understanding about the things I had lost and what led me to addiction. I had to rebuild that myself. But in terms of the LSI-R, I was red hot favourite to fail my drug program. Two guys who had a lower risk than me overdosed and died. If you had bet a dollar on me, you would have lost it. Carly supported me and I took control of my integration to keep myself away from drugs, crime and anti-social people.”

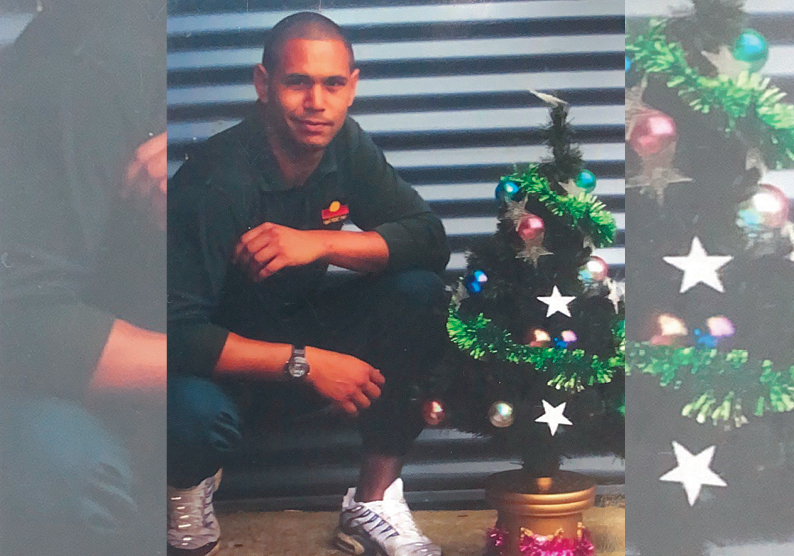

Bugmy Justice Project lead, solicitor Trent Shepherd

Bugmy Justice Project lead, solicitor Trent Shepherd

Holding space

Deadly Connections advocates for culturally safe and holistic sentencing approaches for Aboriginal adult offenders. It partnered with the National Justice Project to pilot an experience report that amplifies the voices of Indigenous people and their community in the courtroom. In Bugmy v the Queen 2013, the High Court considered the issues involved with sentencing Aboriginal offenders and stated it was necessary to have “material tending to establish” an individual’s background and history.

The Bugmy Justice Project implements the principles from this landmark case by identifying the racial, cultural, and historical factors specific to Indigenous people. The reports provide a set of background factors for judges and magistrates to consider on sentencing, and outlines alternative pathways to incarceration and wrap-around support available from therapeutic services like Deadly Connections.

Bugmy Justice Project lead, solicitor Trent Shepherd, is in the process of working with Legal Aid, the Aboriginal Legal Service and private solicitors to take referrals for the project. To be eligible, offenders must be over 18 and have been incarcerated on more than one occasion; have pled guilty and be awaiting sentence or applying for bail; and have at least eight to 12 weeks before their next court date in the District Court or higher. “People are being incarcerated many times and things aren’t changing. One of my goals is to get these reports embedded in legislation, because currently this is optional. We want to do more work with politicians to highlight the importance of diversionary measures,” Shepherd says.

Mundine adds: “We are directing this program to where the data tells us the most entrenched people are. The criminal justice process isn’t set up to treat anyone. It’s a punitive approach. You are accused of said crime, which equals said amount of time in custody; the process doesn’t care if you’re homeless and your father killed himself. People are told, ‘just make better choices and don’t break the law’.”

Mundine leverages his newfound leadership role in the Aboriginal services space to elevate the voices of his community to national and global platforms. He lectures on a subject called Indigenous Perspectives on the Criminal Justice System at UNSW, delivered a speech at TEDxSydney in 2020, and was invited to speak in front of the United Nations Human Rights Commission, to address world leaders about the unjust minimum age of criminal responsibility in Australia.

“It’s screwed up that I had that experience, but at the end of the day, when I sit down with my kids, I can say, ‘I grew up to be the person I wanted to be’. The people that I was surrounded by growing up were still involved in the criminal justice system. I never had a strong black man to say, ‘you can do better’.”

“I needed someone to hold space for me, to not write me off for the poor decisions that I made. I never knew what adult I wanted to be, but I am now the adult that I needed.”