How do participants in the criminal justice system view the people who hold power? When leadership wavers, individuals are forced to take charge of their own story. In this two part series, we investigate seemingly opposite experiences that converge to tell a powerful tale of mistrust, loss, and recovery.

“Beyond reasonable doubt is a high bar,” defence lawyer Andrew Tiedt tells the Law Society Journal when asked about the way participants in the criminal justice system see fairness. The Sydney CBD coffee shop around him is buzzing with suits, silks, and wigs, many chatting about the impending outcome of the Chris Dawson murder trial in late August.

Tiedt, Director of J Sutton Associates, has worked in criminal defence for 15 years, representing defendants charged with the full gamut of criminal offences, from driving to sexual assault and murder.

“I once heard someone say that courts aren’t about finding out what really happened, it’s not about trying to get to the truth of the matter,” he says.

“It’s about working out whether the admissible evidence proves beyond a reasonable doubt that person committed the offence. That might mean someone gets off on what some call a technicality. Or it might mean that, even though someone has done something morally reprehensible, they haven’t committed a criminal offence.

“Is that fair? You’re entitled to say no.”

This goes to the heart of the public’s misconception about the criminal justice system, and to the heart of how trust can be built or broken. Tiedt draws this explanation from the thousands of cases he has worked on: an individual’s view of the “system” is coloured by the result.

“Perceptions are filled in through anecdotes. That could mean your uncle went to jail for something he said he didn’t do, or something you see in the media, or some experience you had as a victim or witness.

“My role isn’t necessarily to restore faith in the system. Although that is often a happy consequence. My role is to defend my clients, to ensure they get a fair trial. If I can improve their perception along the way, that is great.”

Research by the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research released in 2020 suggests that confidence in the criminal justice system (CJS) is associated with higher levels of knowledge about it. A random sample of 2000 NSW residents were surveyed, and the results are stark.

Confidence was higher among men, young people, the highly educated, people on higher incomes, and those residing in metropolitan areas. It was lower for people recently exposed to crime and those who mistakenly believe crime rates are rising.

The majority of those surveyed were confident the CJS respects the rights of the accused and treats them fairly. However, two out of every three believed sentences handed down by the courts are “too lenient”, and only 44 per cent expressed confidence that the CJS meets the needs of victims. From 2007 to 2019, overall confidence levels did not improve, and punitive views of the system were common.

Greg Barns, human rights barrister and the national criminal justice spokesman for the Australian Lawyers Alliance, tells the Journal that lawyers need to see themselves as leaders, to find solutions and to advocate for change in the CJS.

“The legal system is difficult for people to understand. Even court houses can be bewildering. It is up to lawyers to communicate with their clients, so they fully understand the process,” Barns says.

“The language of courts needs to be changed and modernised. Terms like ‘adjourning the matter sine die’ put people off. I think wigs and gowns put people off, too. The austerity, the formality, the pomposity of the law, means that people either have a cynical view of it or they are scared.”

THE VICTIM EXPERIENCE

A teenage girl’s bleeding body limp on the asphalt. A family’s desperate attempt to reach her before it’s too late. A killer’s name spoken breathlessly from shaking lips. A murderer sitting stoically in the courtroom dock.

These are the memories Mandy Burgess must compartmentalise to live her life as painlessly as possible, notwithstanding the countless years of counselling, sessions in homicide victim support groups and stints in trauma institutions. “I am not an emotional person. I used to be many years ago. I am the opposite of someone who wears their heart on their sleeve. Because of what happened to us, it is the way I’ve become,” she says.

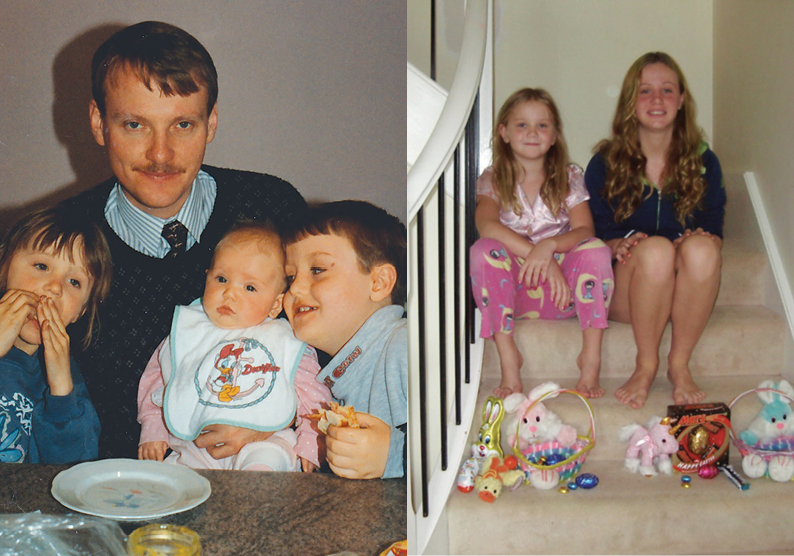

When Mandy sits down with the Journal on a clear day in August, she has recently celebrated her 60th birthday. Sparkly cards sit decoratively atop drawers in the living room of the home she shares with husband Chris in Sydney. Pictures of their three children occupy frames, and colourful artworks line the walls, many painted by her 15-year-old daughter, Tania. A trendy candelabra sits alight in the hallway: a gift from her daughter, now a tribute to her life.

Mandy thumbs through fading photo albums and youthful faces beam back. There are two children now well into their adult life, but Tania will always be a teenager, Mandy says. “Tania is trapped in a time bubble.”

Mandy recalls memories of her daughter’s formative years before they were stolen: “She was extremely creative and loved to make things to give as presents. She was very tall and played a lot of sport, she loved ballet.

“At one time, I looked at a picture of her and I knew the face, but I couldn’t think back to where the memory was from. That is how sick I was.”

Seventeen years ago, on 19 July 2005, the Burgess family were thrust into the criminal justice system. They had returned home to Forresters Beach, a sleepy beachside community on the NSW Central Coast, after a skiing trip. It was the first day back at school for the term.

Tania, the middle Burgess sibling, alighted from the bus at her regular stop shortly before four in the afternoon, as she did on any other day. She took the standard short cut through Forresters Beach Resort car park, planning to walk the short distance to her home beyond it. But a 16-year-old boy who usually caught the same bus as Tania was waiting – he had truanted from school that day. Catching Tania by surprise, he stabbed her 48 times with a knife, puncturing her heart. She tried in vain to fight off her attacker, as proven by the defensive wounds on her legs and arms.

A guest at the beach resort gave evidence she saw a girl lying on her back with a boy sitting on top of her, punching and stabbing. The witness yelled for the boy to stop before he ran off, leaving his victim for dead.

After calling Tania’s phone and being answered by a bystander, Mandy and Chris rushed to help their daughter. As she lay dying in their arms, she summoned the strength to say a few crucial words before she stopped breathing: the name of her killer, his class and his school.

The offender can be identified only as DL; his name is sealed by legislation to protect juvenile offenders, the rationale for which has baffled the Burgess family for the last 17 years.

Where leadership matters

“My trust issues with the criminal justice system go back to before Tania’s murder,” Mandy says, disheartened, at the start of her interview with the Journal.

Four weeks before Tania was brutally murdered and the Burgess’ lives changed irrevocably, Mandy was hospitalised after being assaulted in her home by a boy she didn’t recognise wearing school uniform.

“What are you doing in my house?” she shrieked at the boy. According to Mandy, he responded, “I’m looking for someone.”

The teen left the property and then returned five minutes later. When Mandy confronted him again, the boy allegedly pushed her into a mirror hanging in the hallway, shattering it to pieces. A neighbour heard her screams and came rushing to her aid, trying to catch the boy, but to no avail.

As Mandy recounts the terrifying experience of the youth punching and kicking her as she lay helpless on the ground, she visibly snaps back to the present moment. She speaks with disbelief and frustration about the inaction by NSW police in the weeks following the assault despite her numerous requests to find the person responsible. Mandy says she sees the police as the “gateway” to the criminal justice system, yet when she needed them to step up, they failed her.

Pictures shown at the first identification check yielded no results. And then Tania was killed.

In the days after, Mandy was brought in for a second identification check, and this is when, she alleges, the pieces fell into place: her assailant and her daughter’s killer were the same person. “I had survivor guilt for so long. Tania didn’t live, but I did … If they’d caught him at the time of [my] assault, he may not have gone after her. I always think about that,” Mandy says.

At DL’s trial in March 2008, this evidence was deemed inadmissible due to police error. The NSW Supreme Court jury didn’t hear about the assault, but that didn’t stop them from finding DL guilty of Tania’s murder after only 90 minutes of deliberation.

DL declined to be interviewed by police at the time, and gave no evidence at his trial or during the sentencing proceedings. To the author of the pre-sentence report and psychiatrists who interviewed him, he either denied any involvement in Tania’s death or claimed to have no memory of it.

Mandy and Chris praise the efforts of their prosecutor, who vehemently argued that the “frenzied” murder had a “very clear element of premeditation”, based on DL’s presence at the scene, his truanting from school and his knowledge of Tania’s habits, including the timing of her buses and the way she would go home.

However, on this evidence alone Justice Robert Hulme was “unable to conclude to the high standard of beyond reasonable doubt that the Prisoner’s attack on the Deceased had any degree of premeditation about it”. He found the attack was “irrational”, with “scant evidence” to explain it. “While undoubtedly the prisoner met Tania on the afternoon of 19 July and it was possible that he set out to do so, the evidence does not justify the conclusion that this was his intention,” Justice Hulme concluded.

A former inmate gave evidence that DL spoke to him about stabbing a girl because she rejected him, but the Judge questioned the witness’s reliability, finding no evidence to prove this assertion.

The Judge assessed DL’s character, as described by witnesses, as that of a “shy, quiet boy who wouldn’t hurt an ant”. Three psychiatrists testified, each giving varying explanations for the attack, including that DL had an anxiety attack or was in the early stages of schizophrenia. One doctor couldn’t find any psychiatric reasoning for the murder, but Justice Hulme concluded that DL acted under the influence of psychosis.

Critically, the Judge noted comments from one doctor, who determined: “If one looks at the risk factors that are more likely to be associated with recidivism in the future, [DL] manifests few of those and based on that you would place him at a low risk of future violence.”

“If I approached the Judge five years later, would he have remembered us? Or are we just another case file number?”

DL was sentenced to a non-parole period of 17 years, with a maximum term of 22 years. This was reduced on appeal by four years, and DL has been eligible for parole since 2018. He attempted to appeal his conviction and sentence several times, each time forcing the Burgess family to confront the fact that their daughter’s killer is not remorseful.

“I truly believe he should have got a longer sentence, regardless that he was only 16 at the time. There is so much emphasis on the teen years, but where does a Judge draw the line between a child not knowing they’ve hurt someone and a grown teenager who can contemplate a premeditated murder?” Mandy says.

“If I approached the Judge five years later, would he have remembered us? Or are we just another case file number?”

‘A tightrope bridge’

For more than three decades, Howard Brown has been a victims advocate, looking after 60 families who have endured the worst of humanity: from rapists to paedophiles and murderers. Not having a right of appearance in court, he represents his victims in front of the State Parole Authority (SPA) and the Mental Health Tribunal. Though the now 68-year-old spent six years studying to be a lawyer, a pesky taxation subject prevented him from obtaining his degree, instead propelling him into insurance investigation work.

Brown is described by his clients as one of the most humble, generous, and kind-hearted people they have ever met. He is the leader they needed to navigate the criminal justice system, helping them find light amid the darkness of the court process. Tragically, his skill comes from his own experience as a victim.

In August 1987, Brown’s friend Penny was raped at knifepoint after an ex-lover broke into her unit. The offender was released on bail and breached his conditions on eight separate occasions. Brown, concerned for Penny’s safety, drove her to and from work. But in January 1988 Brown’s father suddenly passed away. While preparing for the funeral, he asked his friend Andrew to drive Penny to work instead. That morning, Penny’s attacker turned up to her apartment with a gun, and when Andrew confronted him he was shot dead.

“The next day, I buried my father. I delivered the eulogy, but if you offered me a million dollars, I could not tell you anything about the funeral because I just don’t remember it,” Brown says.

“Penny’s offender was on the run for 20 months. Police were not making any effort to find him, so I started to … He was found not guilty of murder but guilty of manslaughter on the grounds of diminished responsibility (or temporary insanity). I thought, ‘nobody cares about the victims’.”

From a place of sheer desperation and grief, the Victims of Crime Assistance League (VOCAL) was born. Among many feats, Brown and the team successfully lobbied the NSW government to abolish the term of diminished responsibility and establish victim impact statements.

In the last 32 years, Brown has identified a host of areas where the criminal jurisdiction fails victims, including not being “parties to the proceedings” like in civil cases. “One of the biggest complaints I get is that as a victim of crime, all you are is a witness for the prosecution,” Brown says.

“One of the big things we did in VOCAL was actually prepare witnesses. When I was giving evidence, the Crown said to me, ‘Why did you think it was the accused that shot your friend?’ I was not allowed to say, ‘because he has tried this eight times before’. That evidence was not admissible. You are asked to tell the truth, but you aren’t allowed to.”

Brown’s deep knowledge of the law and lived experience resonated with the Burgess family, who felt completely alone in their journey with the CJS. Brown represented the family at DL’s parole hearing in July this year.

With DL’s sentence ending on 18 July 2023, the SPA was confronted with a difficult choice: to release him on parole under strict conditions or to do so at the end of his sentence unsupervised. Correctional Services reported DL had completed his therapeutic treatment pathway in custody, and accordingly developed a highly comprehensive post-release plan for his supervised reintegration into the community. On 1 August this year, DL was released.

“That is where it becomes problematic for the State Parole Authority, because unless the bloke is Hannibal Lecter, the only option you have is to release a person,” Brown says.

“The last thing any of us want is for DL to walk out at the end of his term without any form of supervision. Hopefully while he is on this 12-month parole period, we will be able to determine how he is assimilating. If he is not responsive to psychologists, psychiatrists, and community corrections officers, we will be able to establish sufficient probative evidence to make an application for an extended supervision order and extend his parole for up to 3 years.”

For Mandy and Chris, the parole hearing was the culmination of an arduous merry-go-round ride they have been on for the last 17 years. “DL couldn’t address us at the hearing and say, ‘I am truly sorry for what I did 17 years ago’. He has never been remorseful about it,” Mandy recalls.

“I remember walking out of the parole hearing relieved to think this part was closing. How many appeals, how many courts we went through! Sometimes we didn’t attend, we were sick of it.”

The criminal justice system is like a tightrope bridge. If we step the wrong way we fall off; that means we stop fighting. But the rope is never ending.”

A veil of anonymity

The Burgess family continues to fight for justice for future victims. They are campaigning for changes to open justice legislation, in particular the prohibitions around concealing the identities of juvenile offenders. An online petition has garnered almost 150,000 signatures.

In July 2022, NSW Attorney General Mark Speakman tabled a 600-page report by the NSW Law Reform Commission (LRC) in Parliament, after three years of robust consultation and research with members of the justice system, community organisations and academics.

Under the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987, any child involved in criminal proceedings in NSW, whether as a defendant, witness, victim or otherwise peripherally attached (for example, a sibling), cannot be identified.

There are exemptions. The legislation aims to compromise between the rehabilitation of child offenders and open justice by allowing a court to determine where the balance lies in each individual case at the time of sentencing. But a court must consider the level of seriousness of the offence, the effect on the victim’s family and the offender’s prospects of rehabilitation. In DL’s case, no application was made when he was sentenced or re-sentenced.

Mandy and Chris made a submission to the LRC, arguing in the interests of community protection, and suggesting the prohibition not apply where the offender is sentenced to more than 10 years, subject to some exceptions such as mental health issues and cognitive impairment.

“It was DL’s name that Tania said just before she died. Can’t everybody else know his name? If she wouldn’t have said his name, he may never have been found,” Mandy implores.

“Our view is that, to be truly remorseful, they must take full responsibility for their crime, and therefore to hide behind the veil of anonymity is not taking full responsibility for the crime. It is not a form of anger or retribution. We have moved on from our anger, but do not wish our daughter’s death to be without some lessons being learned by everyone involved in the administration of justice”.

The LRC’s new proposal hasn’t changed this prohibition, but instead recommends providing new mechanisms for a court to allow the publication of a juvenile offender’s identity after proceedings have concluded.

Prisoner advocate Greg Barns says changing the prohibition to allow for publication would impede an offender’s rehabilitation, potentially throwing them back into an ugly prison cycle. “What we need as a society is for an offender to be able to reintegrate as quickly as possible and live out the rest of their life without re-offending. That is in all our interests,” Barnes tells the Journal.

To this day, the Burgess family are still haunted by what happened to their daughter, as they are by the pain of not knowing why she was taken from them.

Hindsight is a useless tool in this case, but, when asked what would have aided their experience with the CJS, Mandy takes a long time to answer. “It might have been a different perspective if DL pled guilty, said sorry, been remorseful, done all his rehabilitation courses throughout the years,” she responds.

“But we’ve still lost our daughter. There is no justice. Once someone is gone, they are gone. For us, it’s more about keeping the community safe.

“I truly believe that there isn’t much out there for the victims. It is all about the perpetrator’s side: the road they run of rehabilitation, work release programs, and then being sent on their way. But for our side, we have a victim impact statement only. Unless the media steps in and hears our side of the story.”

Coming next week: Part two, insight into offending