The newspaper is a great power, but just as an unchained torrent of water submerges the whole countryside and devastates crops, even so an uncontrolled pen serves but to destroy.

Three new Australian laws seriously undermine media freedom.

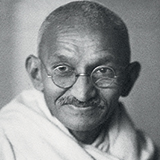

Mahatma Gandhi has become something of a two-dimensional figure, almost a caricature of himself that does him no justice. He is as mythologised as he is misunderstood, but quite rightly he also is lionised as one of the greatest political thinkers and peace-makers of the 20th century.

Gandhi was first and foremost a lawyer and politician. But few people know that he was also a journalist and in that regard I feel a particular admiration for Gandhi. He began his professional life in South Africa, defending the Indian community against the injustices of the apartheid state and to support that cause he launched and edited a weekly newspaper, explicitly aimed at informing South African Indians and encouraging debate. He continued as an editor in India with two more publications. And, while all his papers were aimed at supporting his political ideas, they all were underpinned by an unwavering commitment to fact.

If we can boil down Gandhi’s philosophy to one fundamental idea, surely it must be that peace, security and dignity can be guaranteed only when we respect the human rights of all. It’s an idea that underpinned his strategy of non-violent resistance.

Gandhi was no fool. He might have been a pacifist, but he understood profoundly just how powerful non-violence really was as a way of confronting the British authorities who controlled Indians with their military and police.

“The first principle of non-violence is non-cooperation with everything that is humiliating,” he says. He knew how infuriatingly impossible non-cooperation would be for the British to manage. But he also understood that fundamental respect for human rights is the only way to produce a stable, prosperous system that doesn’t require continued violence to survive.

I would argue that, even for Gandhi, the most fundamental right – the one that underpins all others – was the freedom of speech, the right to self-expression. Without that, Gandhi would be unknown to us. He would never have launched his newspapers. His voice would have been rendered useless. The power of his words would have evaporated.

Gandhi understood this when he began his newspaper career in South Africa. The papers became a tool that helped him inform the Indian community, as a way of encouraging debate, and, most crucially, as a way of challenging and questioning the Apartheid state. But as an editor he also understood the power of the media, both as a democratic tool, and also as a destructive force.

Here is what Gandhi said about journalism: “The newspaper is a great power, but just as an unchained torrent of water submerges the whole countryside and devastates crops, even so an uncontrolled pen serves but to destroy.”

MAHATMA GANDHI

MAHATMA GANDHI

Democracy 101

Now, we have the “War on Terror”. A good friend once dryly quipped that it is a war on an abstract noun. It means whatever anyone wants it to mean. We in the West think it’s pretty clear what this is about. It’s about stopping the slaughter in places such as Paris or random bombings in Kabul and Baghdad, or closer-to-home incidents such as the Lindt Café attack.

But consider what some of the Islamists I met in prison told me. For them, the War on Terror means stopping the drone strikes that hit a hospital in Afghanistan or wedding parties in Waziristan, the barrel bombs that fall in Alepo, and yes – the random arrests, the beatings, and torture in Cairo’s prisons.

This is not a war over anything tangible, with clear lines and distinct uniforms. This is a war over competing world views. It’s a war between western liberal democratic ideas and a particular branch of radical political Islam. And in that war of ideas, the battlefield extends to the place where ideas themselves are prosecuted – in other words, the media. Journalists are no longer simply witnesses to the struggle. We are, by definition, a means by which the war itself is waged.

But let’s go back to Democracy 101. We are familiar with the usual three pillars – the executive, the legislature and the judiciary. But in the classic model of democracy, the media is the fourth estate. It’s there to hold the other three to account, to keep the public informed of the policies that are being enacted in our name and to help oil public debate. It is an integral part of a properly functioning democracy.

I suspect that won’t come as much of a surprise to those of us who happen to live in one of the most stable, harmonious and prosperous places on the planet. And yet in the “War on Terror” we seem to be losing sight of that key idea.

Governments the world over are using that “t” word to clamp down on the very freedoms that made us so successful in the first place. There are the easy examples, of course. Last October, police in Turkey raided the headquarters of a media group and closed two newspapers and two television stations that had been highly critical of the government. The group’s owners have been charged with supporting terrorism.

In China, North Korea and Russia – all the usual suspects – we’ve seen similar attacks on press freedom.

And then there is Egypt. My two colleagues and I were arrested and charged with being members of a terrorist organisation, of supporting a terrorist organisation, of financing a terrorist organisation and of broadcasting false news to undermine national security. What we were actually doing was covering the unfolding political struggle with all the professional integrity that our imperfect trade demands – and that included reporting that was both accurate and balanced. And in this case, balanced reporting involved interviewing members of the Muslim Brotherhood, who six months earlier had been ousted from power after forming the country’s first democratically elected government. In other words, we were talking to the opposition.

I couldn’t have objected to being imprisoned if we had actually committed some offence, if we had broadcast news that was false, or if we really had been members of a terrorist organisation. But at no stage in the trial did the prosecution present anything to confirm any of the charges. Once again, this wasn’t about what we had actually done so much as the ideas we were accused of transmitting. Egypt has gone on to introduce new legislation that makes it a criminal offence to publish anything that contradicts the official version of a terrorist incident. If you check the facts, discover that the government has been trying to cover up some inconvenient truths, and publish what you know, you can be hit with a fine equivalent to $50,000.

Concern in the UK

In case you think this is happening in places with less developed democracies, think again. In the United Kingdom, the ruling Conservative Party has pledged to introduce what it calls Extremism Disruption Orders (EDO). These will restrict the movement and activities of people the government thinks are engaged in “extreme activities”, even if they haven’t broken any law. Innocent people could be banned from speaking in public, from taking a position of authority, or restricted from associating with certain individuals simply because they hold views that run counter to what the government thinks are “British values”, whatever those are. News organisations could also run foul of the law simply by quoting someone who is the subject of an EDO.

And lest we start to feel a little bit smug about our own country, let’s go back to three pieces of legislation introduced by the Australian Government over the past few years that all seriously undermine media freedom in ways I don’t think have been properly understood.

The first was section 35P of the ASIO Act – the new section that deals with the disclosure of information relating to Special Intelligence Operations (SIOs).

Essentially, this prohibits reporting of any undercover operations involving security agents. No responsible journalist wants to expose an ongoing operation, or put security agents at risk, but the new law goes far beyond that. The 35P offence carries a five-year jail term and double that for “reckless” unauthorised disclosure if we ever report on an SIO. And, because there is no time limit on an SIO designation, you can be imprisoned for reporting on one regardless of how far in the past it happened. And that’s despite the fact that reporters will never know what operations have been designated an SIO because that little detail is also secret. So simply looking for information about the work of the security services runs the risk of breaking the law and landing you in prison.

The second piece of legislation is known as the Foreign Fighters Bill. The killer line here is the new offence of “advocating terrorism”. The media union – the Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA) – argues that it suppresses legitimate speech and advocacy, but the MEAA is worried particularly that it could include news stories that report on banned advocacy or even fair comment and analysis.

The third legislative tranche is the Data Retention Bill requiring telecommunication companies to keep metadata for at least two years so it can be accessed by a variety of agencies, including security organisations and the police.

The problem for journalists is that it gives the authorities both the tools and the legal cover to explore their contacts with sources. The government has introduced a fig leaf protection that establishes public interest advocates who are supposed to help judges decide whether to issue a search warrant to investigate a journalist’s data, but the journalists themselves won’t be consulted because the whole process is done in secret. And, anyway, there is no provision requiring the authorities to seek a warrant for a journalist’s sources.

If you’re a public servant and you have information on some misdeeds within your department, and decide that you have a moral obligation to expose it, simply picking up the phone and calling a newspaper makes you a potential target of the security services. It makes confidential whistle-blowing almost impossible without risking a prison term.

The government keeps claiming that none of these measures is directed at silencing the media. That may be true, but each in their own way has a corrosive effect on the ability of journalists to do the job that basic democratic theory demands of us.

How can we, the public, keep track of the government’s security policies – surely one of the most critical areas of the government’s work – when the media can’t report on abuses of that policy for fear of winding up in jail? How can we have a rational public debate about what constitutes Aussie values when we can’t quote people who hold views from across the social and political spectrum? How can we encourage insiders to blow the whistle on government misdeeds when we can’t ever guarantee that our sources will remain safe?

While the media has a responsibility to lift our game and restore some measure of public confidence, politicians also must recognise what we stand to lose if they are too swift to criminalise free speech or limit the work the media does. It is about nothing less than defending one of the most fundamental pillars of our democracy.

Let me quote Mahatma Gandhi: “In a true democracy, every man and woman is taught to think for himself or herself.” This cannot happen if the media isn’t allowed or simply is incapable of giving every man and woman the information they need to think for themselves, and take part in our democracy.

The danger of our laws

PROFESSOR GEORGE WILLIAMS explains how a number of new Federal counter-terrorism laws impinge on the freedoms of press and speech.

Section 80.2C of the criminal code

This makes it an offence, punishable by five years’ imprisonment, to advocate the doing of a terrorist act or terrorism offence where the person is reckless as to whether another person will engage in that conduct as a result. The offence is triggered merely by a person’s speech, with no further conduct required. The law states that a person advocates terrorism if he or she “counsels, promotes, encourages or urges the doing of a terrorist act or the commission of a terrorism offence”. In doing so, the law goes well beyond the traditional proscription of incitement to violence.

The Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Amendment (Data Retention) Act 2014 (Cth).

This establishes a regime for the mandatory retention of metadata for two years by communications service providers. Metadata refers to information other than the substance or contents of a communication – such as the time, date and location of a phone call, email or SMS. By accessing metadata, agencies are able to learn whether a suspect was in a particular location at a particular time, or communicated with a particular individual. This data may be accessed by enforcement agencies without a warrant where access to metadata would be reasonably necessary for the enforcement of a criminal law, to find a missing person, or to enforce a law that imposes a pecuniary penalty or protects the public revenue.

Metadata can be used to reveal the identity of journalists’ confidential sources. The law provides only weak protection against this. A “journalist information warrant” must be sought where a communications service provider knows or reasonably believes that metadata relates to a person who is a journalist working in a professional capacity. Access to a journalist’s metadata may be granted by an issuing authority if “the public interest in issuing the warrant outweighs the public interest in protecting the confidentiality of the identity of the source”. This test is likely to be readily satisfied where criminal sanctions are in issue.

Section 35P of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979 (Cth).

This provides a penalty of five years’ imprisonment where a person (a) discloses information, and (b) the information relates to a special intelligence operation (an undercover operation approved by the Attorney-General in which officers from the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) are granted immunity from civil and criminal liability). There are no other elements to this offence, such as an intention to prejudice security or defence. The person need not know that the information relates to an operation, so long as they are reckless as to that fact. There is no exemption for disclosing information in the public interest.

By criminalising the disclosure of any information relating to a special intelligence operation, 35P directly impacts on the ability of media outlets to report on ASIO’s activities. Journalists will face years in prison for revealing information that relates to an operation, even if they reveal that ASIO officers were involved in dangerous, unlawful or corrupt conduct.