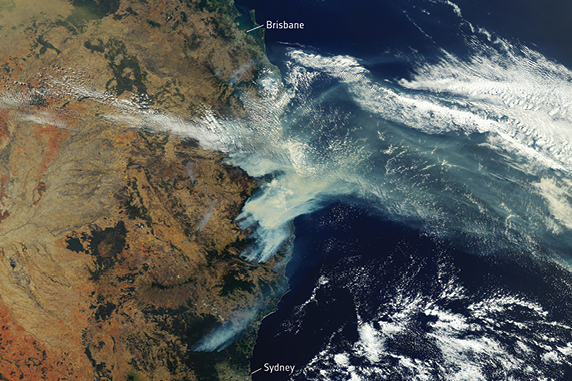

After a summer of bushfire devastation and years of drought, our regional communities are facing a steep road to recovery. Lawyers at the coalface of the disaster response tell how they go about caring for clients who’ve lost everything.

A man forced to choose the shortest wall of flames through which to drive his tractor. A woman sheltering from flooding rain in a caravan after losing her house in a bushfire. A family in tears as debt collectors demand the keys to their property. Farmers wrenching dead stock from empty, muddy dams.

These are the stories lawyers in drought- and bushfire-affected communities will remember forever as they help others navigate the trauma of disaster.

Hearing and responding to encounters of suffering, loss, and escaping death can take a toll. And according to the Centre for Rural and Remote Mental Health, those in “helping professions” – like the law, emergency services, and social work – are at the highest risk of suffering vicarious trauma.

One of the centre’s Rural Adversity Mental Health Program coordinators, Steve Carrigg, says work in disaster recovery can be rewarding, but sometimes that’s not enough.

“I recently heard an expression which sums it up well: ‘The expectation that we can be immersed in suffering and loss and not be touched by it is as unrealistic as expecting to walk through water without getting wet’,” he tells LSJ.

According to Carrigg, managers and workers need to recognise in themselves and their colleagues the symptoms of trauma, including anxiety, social isolation, withdrawal, and difficulty regulating emotions like anger.

Ways to combat stress and vicarious trauma, he says, include regular team debriefs and encouraging workers to take breaks and use their leave entitlements. Small things like having a bright and colourful workplace can help, along with exercise and spending time with people who uplift you.

LSJ spoke to lawyers around NSW who have helped drought, bushfire and flood victims about how they look after their clients and, importantly, themselves.

Choking on dust

Stephanie Hughes is blunt when describing the misery of the drought.

“The heat, the dry, the dust – it’s very real when you walk out your door and you’re smacked in the face with a mouthful of dust,” Hughes says.

“The animals have no water and are getting smacked with the same dust. The land that you farm is blowing away, literally.”

Hughes, the director of Hughes and Co in Forbes and Parkes in the central west, sees drought-affected clients daily.

There are those struggling with finances and debt, some in the midst of family breakdowns, and others trying desperately to sell land no one wants to buy.

“A lot of these people are out in the dust all day, or out in the dry. They get up and feed stock and then they come home and have a dirty, dusty house. Then they open their emails and try to work out how they’re going to pay their bills. It’s a vicious cycle all day long,” she tells LSJ.

Hughes farms on a property near the Lachlan River, so can relate to her clients. She knows never to broach the weather, as rain forecasts bring patchy falls, or disappear altogether.

“These people are coming in and I’m changing the subject. I’m distracting them for 10 minutes. I’m doing what I need to do with them and I’m giving them some light at the end of the tunnel,” she says.

“The biggest part of a country practitioner’s role is more of a psychological one than anything else. You’re helping people through some very difficult times.”

Hughes says she gets through by doggedly holding on to her positive attitude.

“I’m thankful every day for the things that I do have, rather than dwelling on the things that I don’t have. I try to convey that to clients: let’s be thankful for our health, let’s be thankful for our family, let’s be thankful for our friends.”

Men in black

Doug McKay was eating Easter Sunday lunch with friends when a client called him in distress.

It was in the middle of a drought many years ago, which was affecting irrigators around Warren in the state’s northwest.

“[He said], ‘There are some men in black suits and sunglasses here and they’ve told me I need to hand over the keys to the farm and all the vehicles’. It was dreadful. His wife was inconsolable, they were being locked out of their house,” McKay tells LSJ.

McKay was a farmer in Warren before, at age 30, he decided to study law and was admitted in 1979.

His farming clients are often large-scale operators with enough assets to keep them going through a drought. But McKay saw plenty of people pushed to the brink during his time as a director of a financial counselling service in Bourke.He says the best way to help people is to drop formalities and have a conversation.

“It helped that I’d been a farmer and a grazier just like them. When they were talking about day-to-day things on their properties, I could relate directly to them. It was just part of country town practice,” he says.

“Some lawyers are different, but I always dressed relatively casually. I only wore a suit when I went to court.

“It was part professional and part social, too. I went to the pub like everyone else on Friday afternoon and I was partly one of them, partly their lawyer.”

McKay now works part time at Peacockes firm in Dubbo, and says he thinks about his work all the time. Golf, restoring vintage cars, going to the pub, and visiting the coast helps take his mind off things.

“I’ve enjoyed what I’ve done. It’s become a part of me,” he says.

In the line of fire

Regional lawyers frequently confront the same terrifying situations as their clients. Kyrie Couch was at her job as a Legal Aid solicitor when she heard a bushfire was getting close to her Port Macquarie neighbourhood.

As she pulled up to her house that Friday in November last year, she saw flames near the park where her children like to play.

Couch packed some bags and left, taking with her some family photos and the clothes her daughters wore home from hospital as newborns.

She and her husband, their daughters and the dog spent the weekend in Taree, wondering what might become of the home they’d built.

But by Monday, with her house still standing, Couch went back to the office and started working on the bushfire recovery effort.

Couch attended emergency community meetings for Legal Aid, advising people who had lost everything in the fires, including some who were uninsured.

She says she approached people slowly and with care, allowing them to unload while processing their trauma and shock.

Couch was taken aback by the strength some were able to muster at open-forum meetings.

“People were being vocal with the council … they were quite resilient and standing up for each other. A blatant state of shock and not knowing where to start is how they present to legal services,” she says.

“Attending the bushfire recovery community meetings, you are reminded of how fragile life is and the notion that this all ends. And, at the end of it all, what will matter is whether we made a difference.”

She says a supportive workplace, which offers access to an Employee Assistance Program and regular debriefings, keeps her afloat. Exercise, and talking with friends and colleagues also helps.

“I think self-care and wellbeing is a discipline that I owe not only myself but also to the people I live and work with, too,” she says.

Offering comfort

As a senior solicitor in the consumer law team at Legal Aid, Dana Beiglari is used to working with vulnerable people.

But the bushfires have left even more disadvantage in their wake, and Beiglari can hear it in the voices of those calling the Disaster Response hotline.

“I spoke to a woman recently who is insured for the value of her home, but not for elements of her farm like sheds and machinery and livestock,” she tells LSJ.

“Her home and farm were destroyed in the recent fires and since then she’s been living in a caravan. She’s trying to manage the claims process without a computer.

“In the extreme heat and smoke and heavy rains, living in a caravan is a very intense experience in addition to managing the devastating loss of your home and your farm. That really stuck with me.”

Beiglari is based in Sydney, on a team taking calls from south and north coast residents about insurance issues, financial hardship, and property safety concerns.

She says the key is to listen to clients’ stories and respond to their legal questions quickly to bring them some level of comfort.

Beiglari says her trauma-informed training at Legal Aid helps her be compassionate and supportive, but also to draw professional boundaries.

She says managers encourage employees to find a balance, which for Beiglari involves French classes, Pilates, and spending time with her husband and rescue dog.

“When everyone is at work, they work hard, but after that your managers want you to go home and leave your work behind,” she says.

“Support from the management level means you can feel confident booking in a class after work, or a dinner. Those kinds of activities fill up my cup and make me energised to go to work the next day.”

Safe spaces

Beneath a bright painting splashed with bold colours, Orange solicitor Kirsty Evans recalls an intense year.

As the drought raged on in 2019, she saw many distressed clients who needed urgent financial assistance.

Some had lost their crops, leaving them without an income, while others wondered whether their long-held family farms would survive.

“These people are coming to see you for a 9am appointment and you may have gotten up and had the busyness of getting kids off to school, but they’ve been up since sunrise pulling sheep that have perished out of dams,” Evans says.

“You’re getting them to come in and talk about their financial situation, which has kept them up all night and you’re getting them to relive it.”

Evans says it’s crucial to keep clients looking to the future.

“You don’t want to bring them in and say, ‘What do you owe?’ and run through a list, because they don’t want to see that number,” she says.

“It is really important that you’re letting them know the whole community is there … and we will help them find ways to keep moving forward.”

Evans, a director at Cheney Suthers, says the bright and welcoming office is a deliberate effort to calm clients andstaff alike.

“We want to create a space where everyone is happy to come to work the next day,” she says.

The partners exercise together and make sure they debrief, taking 15 minutes to walk and get coffee. The firm recently held a team-building day to talk and share creative ideas about their practice.

“It’s about nice spaces, surrounding yourself with good people, and putting value in them.”

Weathering the storm

Legal Aid solicitor Julie Maron says she became an accidental expert in disaster recovery after floods hit Wagga Wagga in 2010.

Maron’s experience was soon put to use after floods in Brisbane and Lockyer Valley, and in countless bushfires that followed.

“I think we’ve done a tornado as well, so we’ve learnt a lot about how people are after a really traumatic experience,” Maron tells LSJ.

“We make sure we train all our lawyers going into disaster recovery centres about trauma-informed practice and how to talk to clients.”

Maron says asking disaster victims, ‘Tell me what’s happened at your place?’ is a better approach than launching into questions about insurance policies and housing.

“It can be exceptionally traumatic for people to tell those stories because we’re asking about insurance claims and what you’ve lost. That might be the first time they’ve realised what they’ve lost,” she says.

Sometimes danger still lingers when a Disaster Recovery Centre is set up, like during the bushfire that hit the Warrumbungle National Park in 2013, destroying homes near Coonabarabran.

“People were talking to us at the Recovery Centre while there were still helicopters being filled up on the showground,” Maron says.

She says hearing repeated stories of escape from death can take its toll.

“A story about a farmer picking the shortest wall of flame to drive the tractor through … will probably sit with me forever. Anytime somebody is telling us about near-death experiences, the vivid details of that can really stick with you.”

When she’s travelling, Maron finds the nearest swimming pool or the flattest, longest road to run on to help her manage. She also makes sure she keeps in touch with the people she loves.

“It can be really easy just to get caught up in the work and work non-stop. But then you’re no good to anyone,” she says.

“You can’t help people if you’re not OK.”

Maron says one of her proudest achievements is lobbying insurance companies to stop asking disaster victims for detailed lists of everything they’ve lost. Those lists were often impossible to make, and retraumatised people.

“Everybody in Australia wants to help people who have been affected by disasters,” she says.

“I’m just so pleased that I’m qualified to help them in this wonderful way.”