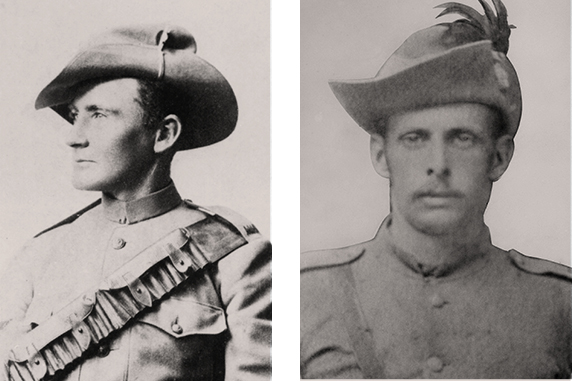

James Francis Thomas achieved notoriety as the lawyer who represented Harry “Breaker” Morant in his controversial trial for murder during the Second Boer War. Lawyer JAMES UNKLES has spent a decade investigating the case and hopes to secure posthumous pardons for Morant and his co-accused. As the 118th anniversary of Morant’s arrest falls this month, Unkles shares an exclusive extract from his new book, Ready, Aim, Fire.

All photos courtesy of the Australian War Memorial.

There is a haunting image of James Francis Thomas standing over the freshly dug grave of [Harry “Breaker”] Morant and [Peter] Handcock.

The photo (main image) was rescued from a rubbish dump in Tamworth along with some other papers relating to ‘The Breaker’. Though the photograph is faded and sepia toned, it did not detract from the power of the image, giving it a surreal, dream-like starkness. It shows a tall, thin, dapper man standing over a freshly-dug grave. The body language says it all. The deep regret caused him to stoop sorrowfully over their grave almost as though he was racked by some physical pain.

Thomas, who previously practised in wills, probate and contracts, found himself serving as an infantry officer and then by accident as legal counsel desperately trying to represent three of his countrymen – Morant, Handcock and [George] Witton.

Morant and Handcock both paid the ultimate penalty on the charge of being accessories after the fact to murder, when they were both shot by a firing squad at the direction of British Commander-in-Chief Lord Kitchener.

On 27 February 1902, when Thomas witnessed the execution of Morant and Handcock by firing squad and the imprisonment of Witton for life, his work as a country solicitor could not have prepared him for that experience in South Africa and the profound effect that it had on his life.

It remains one of Australia’s and Britain’s most enduring military and political controversies. For 116 years, the issue of whether Morant, Handcock and Witton were tried according to British law and treated fairly when convicted and sentenced for shooting Boer prisoners during the Anglo Boer War has been disputed. Since 2009, a dogged war of a legal nature has been waged by this author in an effort to persuade the British and Australian Governments to comprehensively review the case.

The trials of these men in South Africa between January and February 1902 ruined Thomas’ life. Thomas might as well have been shot on the veldt with Morant and Handcock. At least their deaths were mercifully quick, but his was slow and lingering. His entire value system had been destroyed and it took him 40 years to die from the mortal emotional and physiological wounds he received in those Courts Martial. It is noted that people die of a broken heart and although it is not a recognised medical condition, in some cases there appears to be no other explanation. Something similar happened to Thomas, possibly post-traumatic stress disorder from which he never recovered.

The first charge of killing [Boer soldier] Josef Visser concerned his execution without arrest and lawful trial. According to the accused, when Visser was caught he was wearing British Khaki and had in his possession a pair of [Captain Percy Frederick] Hunt’s trousers. The criminality of the accused was argued by the prosecution as illegal and contrary to the provisions of military law.

Evidence was deposed from witnesses, including two soldiers who had been in the firing squad that executed Visser. Morant, Handcock and [Englishmen Lieutenant Henry] Picton testified that they had acted under the orders of Hunt to take no prisoners and to execute Boers wearing khaki. Morant also testified that Hunt had told him that he had received his orders from Colonel Hamilton, the Secretary to Lord Kitchener. When called to give evidence, Hamilton denied such orders existed or that he had spoken with Hunt.

The second charge concerned the execution of eight Boer prisoners. The facts as alleged by the prosecution were not disputed by the accused. The prisoners had been captured and handed over to Morant, who stated he had orders to execute prisoners of war.

The accused didn’t testify but handed prepared statements to the court as evidence. Morant stated he followed orders from Hunt and had the prisoners executed, as had been done by members of other irregular units. He also stated that he had been reprimanded by Hunt for failing to execute prisoners in the past. He said he was justified in dealing with prisoners in a summary manner. He claimed that his state of mind was affected by Hunt’s death and he had decided to summarily execute prisoners. Handcock, Witton and Picton gave similar statements. A number of other witnesses stated in evidence that Hunt had given direct and unambiguous orders that no prisoners were to be taken and prisoners had been summarily dealt with in accordance with orders from Lord Kitchener.

Thomas faced a difficult brief. He was only afforded a day to prepare his case and was confronted with representing six personnel, a daunting task notwithstanding the principle that accused persons should be represented in a manner that avoided conflicts of interest. According to [writer Nick] Bleszynski, Thomas did a professional job as defence counsel: “There can be no doubt however that Thomas gave a spirited defence which belied his experience. Despite his background he had little experience in criminal law and next to no experience in military law.”

Thomas only had a short time to converse with his clients, yet according to the MML [Manual of Military Law] a failure to give a prisoner full opportunity of preparing his defence and free communication with others for the purpose, may invalidate the proceedings unless waived under Rules of Procedure 10493. This rule required the Court to balance the right of the accused to an adjournment and preparing a defence against the requirements to proceed with a Court Martial as soon as possible. Did Thomas consider that his duty was to ensure that he was sufficiently prepared to represent the accused? Section 33 of the MML stated: “The prisoner is to have proper opportunity to prepare his defence and liberty to communicate with his witnesses and legal adviser or other friend. The object of the rule is to give the prisoner full opportunity to prepare his defence but not to enable him to postpone his trial.”

MML procedure rule No 13 further provided: “A prisoner for whose trial by court martial has been ordered to assemble shall be afforded proper opportunity of preparing his defence and shall be allowed free communication with his witnesses and with any friend or legal adviser with whom he may wish to consult.”

Rule 13 also stated: “A failure to give the prisoner full opportunity of preparing his defence and free communication with others for the purpose may invalidate the proceeding.”

If Thomas considered this provision, it was not apparent as the Courts Martial proceeded. If he did make application for an adjournment for more time to prepare a defence and this had been refused, he had little choice but to proceed. His only other option was to make direct application to Lord Kitchener to intervene as the convening authority. The lack of time for Thomas to prepare the defence case in accordance with provisions of the MML certainly prejudiced a fair trial, and should have invalidated the proceedings in accordance with Rule 13 of the MML. Had Thomas had time to seek instructions from the accused he may have used the opportunity to consider matters such as motions for separate trials and separate representation. [Author E.] Gunter in Outlines of Military Law explained the rights of an accused in preparation of his defence in reference to MML. Gunter stated that in the interests of justice an accused must be afforded a number of privileges, including: be given as much or less time as is practicable before trial; an accused may make a statement in mitigation of punishment; may call witnesses and examine witnesses in defence; and may make a defence and ask for reasonable defence.

It is extraordinary that the accused, who were arrested on 21 October 1901 (Morant about a week later), were placed in solitary confinement for three months while a court of inquiry was conducted and they were denied any contact with relatives in Australia and Government representatives. Even the military chaplain Brough was not permitted to visit them while the inquiry was conducted in such secrecy. The accused were given no information as to their possible fate and no opportunity to consult Thomas until the night before their trials commenced on 16 January 1902. Despite the best efforts of Thomas and the persuasive evidence in favour of an adjournment to prepare for trials involving very serious charges, fairness did not prevail in accordance with the MML.

Lord Kitchener did not give evidence as a witness at the trials. Instead his secretary, Colonel Hamilton, appeared. He denied the existence of orders that prisoners were to be summarily shot.

With the luxury of post-trial research, many documents were discovered that suggest Lord Kitchener had issued orders about the treatment of prisoners, including execution for those caught wearing khaki.

Some of these documents included an order issued by Lord Kitchener on 3 November 1901 to British Commanders in South Africa, two months prior to the Courts Martial: “In certain cases of Boers captured disguised in British uniform I have had them shot, but as the habit of so disguising themselves before an attack is becoming prevalent, I think I should give a general instruction to Commanders that Boers wearing British should be shot on capture.”

The shooting of prisoners was a controversial aspect and one that has attracted comment by historians. Considered in context of a war being fought by regular British soldiers (who were versed in the intricacies of military law) and colonial volunteers (who were ignorant of laws of war), it clearly provided Thomas with a significant hurdle to address in his defence of the accused.

Perhaps fearing that Lord Kitchener may be accused of conspiring to murder Boer prisoners, evidence (including the testimony of Hamilton that no such orders were in fact issued by Lord Kitchener) emerged that what Lord Kitchener did was approve the execution of prisoners only after they had been tried by Court Martial and had not condoned summary execution.

This interpretation was favourable to Lord Kitchener and challenged his critics who claim that his order was a ‘green light’ to execute prisoners without trial.

However, critics of Lord Kitchener claim that if Morant and Handcock were guilty of murder and that such orders did exist, then Lord Kitchener should have been charged with conspiracy to commit murder. Had Thomas been successful in preparing the defence case, he may have located additional witnesses and documentary evidence that orders to summarily shoot prisoners had existed. Adequate time to prepare the defence may have ensured that Thomas could have arranged to serve Lord Kitchener with a subpoena to appear as a witness so he could be examined about the orders, including the one of 3 November 1901.

If this had occurred, Thomas could have secured acquittals on all the charges of murder or inciting to murder. In the case of conviction, proof of Lord Kitchener’s orders could have provided Thomas with persuasive mitigation to argue that Morant and Handcock be shown mercy and not sentenced to death.