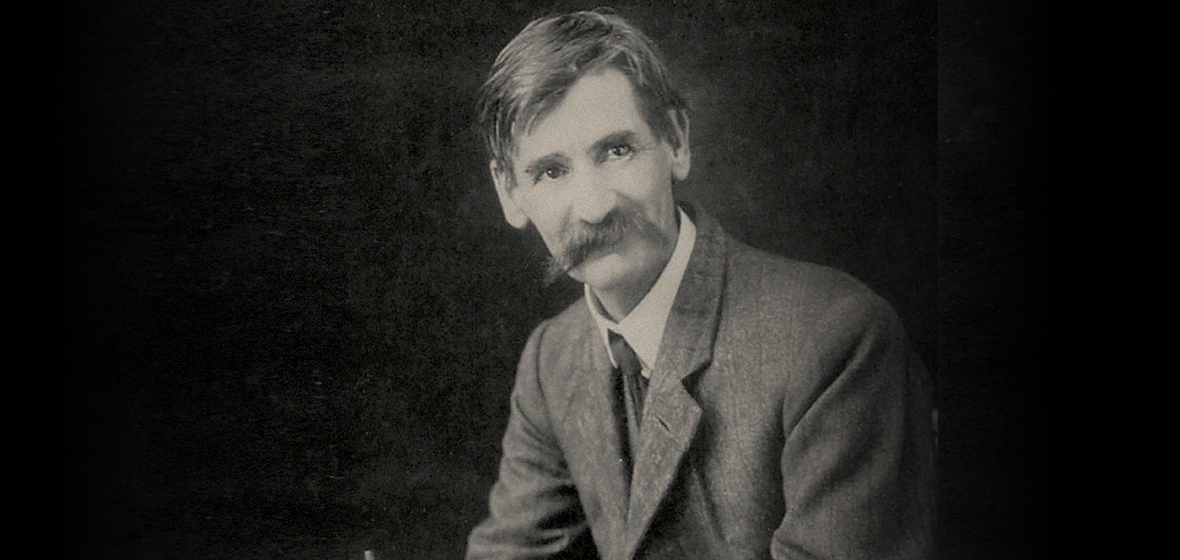

Henry Lawson may have been one of our greatest storytellers and poets, but he was also likely a violent drunk. When his wife divorced him, she dropped domestic violence charges in exchange for 30 shillings a week in child support. Such deals are still made today. KERRIE DAVIES examines historical and modern attitudes and asks if anything has really changed.

Case no. 4676 Lawson v Lawson, is written in calligraphy, rolled in a ribbon and stored at the State Archives and Records Authority of NSW. The file details the judicial separation of Australian poet and short-story writer Henry Lawson and his wife, Bertha, in June 1903. Bertha’s detailed affidavit to the NSW Supreme Court, republished in full in A Wife’s Heart (University of Queensland Press), alleges that Henry was habitually drunk and cruel, two of the grounds for divorce at the time. The other grounds were neglect of domestic duties, desertion, extended imprisonment, and adultery.

The courts heard the petitions of women (and men) who wanted a divorce. If the couple had children, the courts ordered that one party pay child support. Authorities enforced the orders and defaulters were jailed, as Henry found out to his misery. He was jailed nine times at Darlinghurst Gaol, spending a total of 159 days behind bars between 1905 and 1910.

Henry could have thanked his mother, feminist Louisa Lawson, and her suffragette contemporaries for NSW’s comparatively enlightened divorce laws, which were based on English law.

In the 1950s, Bertha told author Ruth Park that she and Henry first met near her stepfather’s bohemian bookshop, McNamara’s, which was on the site of what is now the Bank of Sydney. Within weeks, Henry proposed and Bertha, 19, accepted after he sent her a poem, “After All”. Their engagement immediately drew protests and warnings; her mother, Bertha McNamara, despite being the “Mother of the Labor Party” and an admirer of 27-year-old Henry’s writing, was conservative when it came to the politics of marriage. Bertha told Park that she scrambled out of the window after her mother “blew up Henry” for wanting to marry Bertha – she’d already pegged him as an alcoholic who would be unable to support a family. His publisher, George Robertson, told Bertha that Henry had a “nasty temper” and agreed that he wouldn’t be able to support keeping a home. Regardless, they married in April 1896 in a secret ceremony attended only by strangers as witnesses.

They lived briefly in Western Australia, where Henry searched for gold – however, he had more luck producing creative nuggets. The couple moved to New Zealand, where they worked as school teachers at a Maori Pah (village) near Kaikoura. In 1900, they moved to London when their daughter was just a few months old and their eldest child, Jim, was a toddler. That year, Bertha suffered “lactation and worry” and was admitted as a psychiatric patient at Bethlem Royal Hospital, nicknamed Bedlam.

The Lawsons returned to Australia. By this time, Bertha feared for her safety, going to the police in December 1902. In April 1903, she swore an affidavit to the court petitioning for a judicial separation. In her affidavit, she said: “My husband has during three years and upwards been an habitual drunkard and habitually guilty of cruelty to me.” She continues: “My affidavit consists of the acts and matters following. That my husband during the last three years struck me in the face and about the body and blacked my eye and hit me with a bottle and attempted to stab me and pulled me out of bed when I was ill and pulled my hair and repeatedly used abusive and insulting language to me and was guilty of divers [sic] other acts of cruelty to me whereby my health and safety are endangered.”

Australian National University academic Colin James notes that violence was accepted as part of the domestic fabric at the time. “The law deemed violence by the husband, on the other hand, to be necessary to control disruption in the family and to restrain a wife who threatened the marriage by irrational behaviour or attempting to leave the home. Only in cases where the man ‘went too far’ might the wife successfully complain to the police or divorce courts.” James adds: “The woman’s decision to approach a court of law was always difficult and often dangerous, as she risked provoking her husband to further violence.” He says not only was she risking her physical wellbeing, but she was jeopardising her marriage, standing in the community, financial survival, custody of her children and sometimes her life.

Bertha’s critics point out that the domestic violence allegations were never heard in court because she agreed to drop the charges in return for ongoing child support. As a result, the formal proceedings were brief, with “the whole affair occupying one minute”, according to a letter Henry’s lawyer wrote to his celebrity client in 1903. In Lawson v Lawson, the court ordered Henry to pay 30 shillings a week. The proceedings were similar to the case of actors Johnny Depp and Amber Heard, who recently divorced. She withdrew her allegations of domestic violence in return for a settlement.

Bertha did not petition on the ground of adultery, and it is not known whether she knew of Henry’s rumoured love affair with artist’s model Hannah Thornburn, who inspired several of his poems. By 1903, women had gained equality with men in being able to claim adultery in divorce proceedings if they could prove they lived in NSW.

According to Elizabeth

Van Acker, author of Different Voices: Gender and Politics in Australia (Macmillan Publishers), the Australian women’s movement “fought to change the divorce laws that allowed a husband to divorce his wife on a single act of adultery while a woman had to show adultery plus rape, incest, sodomy, or adultery coupled with cruelty or desertion for two years”.

The suffragette movement framed the divorce debate in Australia, but the gold rushes between the 1850s and 1890s fuelled wider social concerns about men deserting their families as they headed to the goldfields. In her book Deserted and Destitute (Australian Scholarly Publishing), Christina Twomey highlights public support for reforms taking place across the Australian colonies. “Debate on the inclusion of desertion as grounds for divorce in Victoria, for instance, released a flurry of letters and editorials that pointed to the limited employment opportunities available for women responsible for dependent children.” Legal historian Henry Finlay, author of To Have But Not to Hold (Federation Press), concurs that deserted wives and children became a focus for lawmakers concerned with the financial burden it placed on the community.

The Australian women’s movement “fought to change the divorce laws that allowed a husband to divorce his wife on a single act of adultery while a woman had to show adultery plus rape, incest, sodomy, or adultery coupled with cruelty or desertion for two years”.

KERRIE DAVIS, author of A Wife’s Heart

In 1879, The Evening News published: “The records of the Divorce Court in this colony show that the number of suits has been quite as prolific as at first anticipated.” It said the court had heard 106 cases since the Matrimonial Causes Act was introduced in NSW, dissolving 50 marriages and granting 20 decrees nisi, awaiting proceedings.

Feminist Rose Scott, a friend of Bertha’s, wrote to The Sydney Morning Herald to defend her after Henry’s death in 1922. In her foreword to Finlay’s book, The Hon. Elizabeth Evatt names Lady Mary Windeyer, Louisa Lawson, Maybanke Anderson and Scott as among the suffragettes who campaigned for divorce reform and equality.

The women worked with Lady Mary’s husband, William Charles Windeyer, a politician and judge who wanted the court to recognise desertion, drunkenness and abuse as grounds for divorce. For Anderson, it was personal. Windeyer had granted her a divorce in 1892, eight years after her husband deserted her, leaving her struggling to raise her children – only three of whom survived to adulthood. She later married Sir Francis Anderson, the first Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sydney. Although she never sought divorce, Louisa Lawson had her own struggles, leaving her gold miner husband and the drought in Eurunderee, near Mudgee, for a new life in Sydney with her younger children, Peter and Gertrude. Henry, then 16, followed his mother, whom he called “the chieftainess”.

Louisa Lawson supported the Victorian campaign for the Divorce Extension Bill. In her feminist journal, The Dawn, she wrote what would be a prophecy for her daughter-in-law’s predicament: “All the consolation the wife of such a ghoul could reasonably expect from the world is, ‘Why did you marry him?’ About as reasonable a question as asking a condemned criminal awaiting his execution why he committed the act that brought him there. What availeth her to say, ‘I was young, ignorant, inexperienced in the ways of the world. I believed and loved him: he vowed I should not want; he loved me and would love me forever; all these promises he has broken. I have kept mine. He will not support me; he drinks and is cruel to me.’ And the world’s answer is: ‘As you have made your bed so you must lie on it.’ A wife’s heart must be the tomb of her husband’s faults.”

Ironically, Louisa didn’t personally support Bertha in the years after the separation. In letters to Henry, Bertha wrote bitterly that her mother-in-law could “cry her crocodile tears” and “I hate her”. Bertha said Louisa did not help with the children, financially or practically. Instead, Bertha relied on her mother and, from 1905, the courts.

According to Deborah Beck, author of Hope in Hell: A History of Darlinghurst Gaol and National Art School (Allen & Unwin), Henry was jailed in the Debtor’s Quarters, fronting Forbes Street, because alimony was a debt. However, Beck thinks he also spent time in the stricter men’s quarters; Henry wrote in one of his pleading letters for help to pay for his family: “It’s real gaol, grim gaol, this time.”

In the jail’s hospital, he befriended wife murderer David Hanna and wrote poetry such as “One Hundred and Three” about his imprisonment. He used a smuggled pencil, a misdemeanour that earned him solitary confinement.

He railed against “female suffrage” in a thinly veiled account of his own situation in his c.1907 story “Going In”. “They are ‘up for maintenance’ (one for neglecting to keep his alleged wife, the other his alleged child). One has been fined the double amount in arrears, or three months. The other has been ordered to be detained in Darlinghurst Gaol until the amount is paid. The first is sure to be out in three months, and then have worked off his fine and also the amount of her ‘arrears’ – the other expects friends to pay up in a few days, but if they don’t, he might be there for twelve months and ‘arrears’ running on all the time. Then his hope will be to get clear of the Commonwealth and female suffrage in the fortnight’s grace they’ll give him when he does get out.”

After his death, Lawson’s biographers judged Bertha harshly for her court action. Professor Colin Roderick wrote that Bertha “spun the wheels of retribution”, and even though historian Manning Clark recognised that Lawson was violent, he felt Bertha showed no mercy in sending him to jail.

In the days after the publication of A Wife’s Heart, online comments showed that in the politics of divorce, when allegations of domestic violence are made, Louisa Lawson’s lament about harsh attitudes towards women is still relevant today – the protection of a man’s reputation seems to be more important than the experiences of his wife.

Comments in response to an article in The Australian about Bertha’s allegations of violence included: “So he was white and a male, and a respected part of Australian culture. That is all the motivation same [sic] people need.” And “I wouldn’t take to [sic] much notice of the accusations, it was written by a new age feminist”. One respondent to a review of A Wife’s Heart in The Conversation commented that University of Sydney feminists will be “digging up poor Lawson’s bones next and parading them around the quadrangle”. Today, the suffragettes would wear white ribbons and subscribe to the Facebook page “Destroy the Joint”, which, together with Counting Dead Women Australia, records the cases of women killed in domestic violence.

The divorce rate may have skyrocketed in the past 100-odd years, but it’s possible the suffragettes would wonder what has really changed since they advocated for equality in divorce proceedings more than a century ago.