When a Texas lawyer became an internet sensation for blundering into a virtual court hearing with a cat filter over his face, a voice of reason came to his rescue. That voice was Judge Roy Ferguson of the 394th Judicial District of Texas. The now-celebrity judge shares a chuckle plus insights from the pandemic over a less-fraught Zoom call.

On any given day, the internet may catapult armchair nobodies to inadvertent celebrity status.

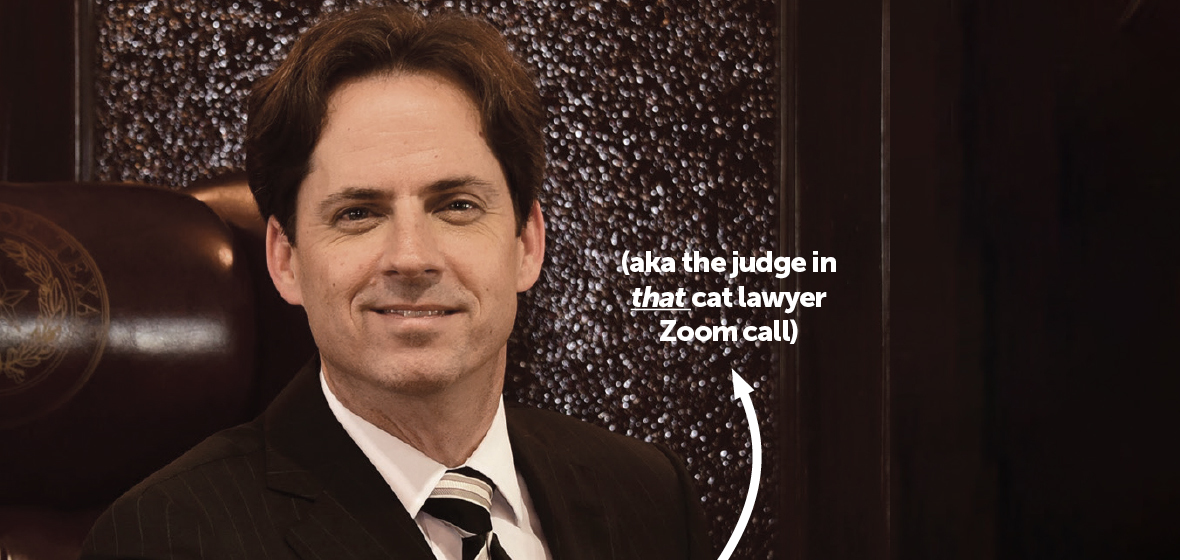

It wasn’t a fate Judge Roy Ferguson of the 394th Judicial District of Texas had contemplated when he logged into Zoom to preside over a straightforward civil forfeiture hearing in February. But since the COVID-19 pandemic hit – barring lawyers around the globe from physical courtrooms and forcing them into live virtual hearings for more than a year – the judge has learned to expect the unexpected.

Ferguson, perhaps best known unofficially as “the judge in that cat lawyer Zoom call”, dialled in to a hearing that has drawn guffaws from millions around the globe. He was still defrosting his fingertips on a brisk winter morning in his living room in rural west Texas when a wide-eyed kitten emerged on screen. It appeared to take the place of county attorney Rod Ponton in virtual court.

“Mr Ponton,” Judge Ferguson said, addressing the cat on screen. “I believe you have a filter turned on in video settings.”

“I’m here live, I’m not a cat,” came the now-viral response from an audibly anxious Mr Ponton.

Ferguson relays the story to LSJ in Sydney via Zoom during what is an early lunch break for NSW lawyers and an evening call for him. His lip occasionally curls into a grin – barely noticeable via a pixelated video across the Pacific – but he explains why it was essential he maintained a steely judicial manner during the infamous “cat lawyer” call.

“When I wasn’t on camera, there’s no question: I was smiling. But your judicial demeanour is what determines the solemnity of the hearing, especially in online court,” Ferguson says.

“If I maintain the dignity of the judiciary in that hearing, then everyone in the hearing remains professional. I was not going to allow our virtual courtroom to become a joke.”

After assisting Ponton to remove the filter, Ferguson saw the lighter side of the exchange and posted a snippet of the vision on YouTube. He Tweeted the video link as a warning for lawyers not to fall prey to Zoom settings saved by a child who has used the computer before them.

The original YouTube video has been viewed more than 10 million times, and countless iterations have been posted by other social media accounts and news websites. Last Ferguson heard, the total number of views across all versions of the video is closer to 2.3 billion.

“I’ve loved seeing the response of the people there in Australia to the interview. I know it was seemed to be well received,” he tells LSJ.

“I was talking to the team on Sunrise – Sam and, how do you say it, Kashi? Kochie. They were delightful and the Australians seemed to love the video.”

Judge Ferguson, 52, a lawyer of almost 30 years, a dog person, and a cat person (his family has one of each), is well-versed in the potential traps and pitfalls of technology in legal work. He has steered his career from the bar to the bench through three decades of innovation. Fax machines became emails, mobile phones gave way to instant online messaging, and, most recently, virtual online hearings enabled the Texas judicial system to carry on through a global pandemic that shut physical courthouses for the best part of a year.

“When I started my career, every law firm had a library and spent an incredible amount of money updating books every month with every case that came out,” Judge Ferguson says.

“I did a lot of work on typewriters. Then we moved from typewriters to word processors, and it became not online, but electronic research, where libraries would mail you a floppy disk once a month with the new cases. It was an absolute battle to convince the old guard to stop using books.

“The email battle was also a big struggle. Some older lawyers wanted to use faxes and letters, they considered emails to be somewhat grotesque, and they liked the old ways. So, we would send an email, and then a week later get a response in the mail. Then came cell phones. Some lawyers refused to get them for 15 years.”

However, the COVID-19 pandemic presented the most seismic shift to legal work Ferguson has seen. In March 2020, almost a year to the day prior to our chat, the Texas Supreme Court closed courthouses across the state in response to the ballooning spread of COVID-19. An administration director of the Supreme Court called Judge Ferguson and told him to install Zoom: he was due to appear in a practice virtual hearing the next day.

“If I maintain the dignity of the judiciary in that hearing, then everyone in the hearing remains professional. I was not going to allow our virtual courtroom to become a joke.”

“I’d never heard of Zoom,” Ferguson admits. “I’ve never used WebEx. And I really didn’t like using any video conferencing software. I thought it was unwieldy and difficult.

“But we had to do something. I believed at the time that we were looking at probably a year to 18 months, minimum, of shutdown in courthouses.”

On 15 March 2020, the State of Texas purchased a Zoom license for every judge in its jurisdiction. The following day, the Supreme Court issued an emergency order authorising courts to hold hearings remotely through video conferencing. Judge Ferguson held his first virtual hearing on 18 March. He says the whole transition took just 10 days from courts closing to becoming completely virtual.

The state has since hosted more than 1.2 million virtual hearings during the pandemic. But of course, the transition has not been without hiccups.

“We’ve had people connect and not realise they are connected yet,” Ferguson says. “One lawyer didn’t realise we could see and hear him and began to say some horrible things about his client. I quickly muted him, but the damage was done.”

Zoom filters aside, Ferguson refuses to let court participants show up looking like something the cat dragged in.

“I’ve had people log in from moving vehicles, which I don’t permit. I had someone log in wearing a big, white fluffy hotel robe with his hair up and wrapped up in a towel,” he says. “Just the other day I had to admonish a lawyer for showing up in a golf shirt. I let him know that this is a courtroom just like in person: if you couldn’t wear it to the courthouse, you can’t wear it in my virtual courtroom.

“Remember that litigants in those virtual hearings are incredibly stressed and worried. They have spent years and thousands or tens of thousands of dollars getting this case ready to present to the court. And it keeps them awake at night. It makes them lose sleep and lose hair. Treat it with the solemnity it deserves.”

In Ferguson’s jurisdiction of 60,000 square kilometres, litigants would previously drive for hours, take days off work, or even purchase flights and accommodation across the country, to reach a courthouse for a 15-minute appearance. Now, they simply take a few steps into a quiet room of the house or office to log in to Zoom on their mobile or laptop.

“If there is such a thing, the biggest benefit to this tragedy that we’ve had unfold is the revolution of access to justice through virtual hearings. It has outpaced anything we imagined,” Ferguson says.

Even as COVID-19 vaccines roll out across the US and life in rural west Texas begins to resemble pre-2020 normality, Ferguson believes online hearings are here to stay. He says the Texas Office of Court Administration conducted a survey at the end of 2020 of more than 1,000 litigants who participated in virtual hearings, of whom 95 per cent reported the hearing was fair in its virtual form. The US Supreme Court also plans to continue using Zoom even when courthouses re-open.

The virtual cat is out of the bag, so to speak, even if it was booted from Zoom.